When an underwater volcano erupted in 2015 it created a new island as the Hunga Tonga Hunga Ha’apai island emerged from the ocean. It would live fast and die young with just a seven-year lifespan from emergence to submergence, but in those short few years, a team of scientists had time to scan the novel island for signs of life. And boy, would they find it.

“These types of volcanic eruptions happen all over the world, but they don’t usually produce islands,” said Nick Dragone, CIRES PhD student who worked on the island, in a statement. “We had an incredibly unique opportunity. No one had ever comprehensively studied the microorganisms on this type of island system at such an early stage before.”

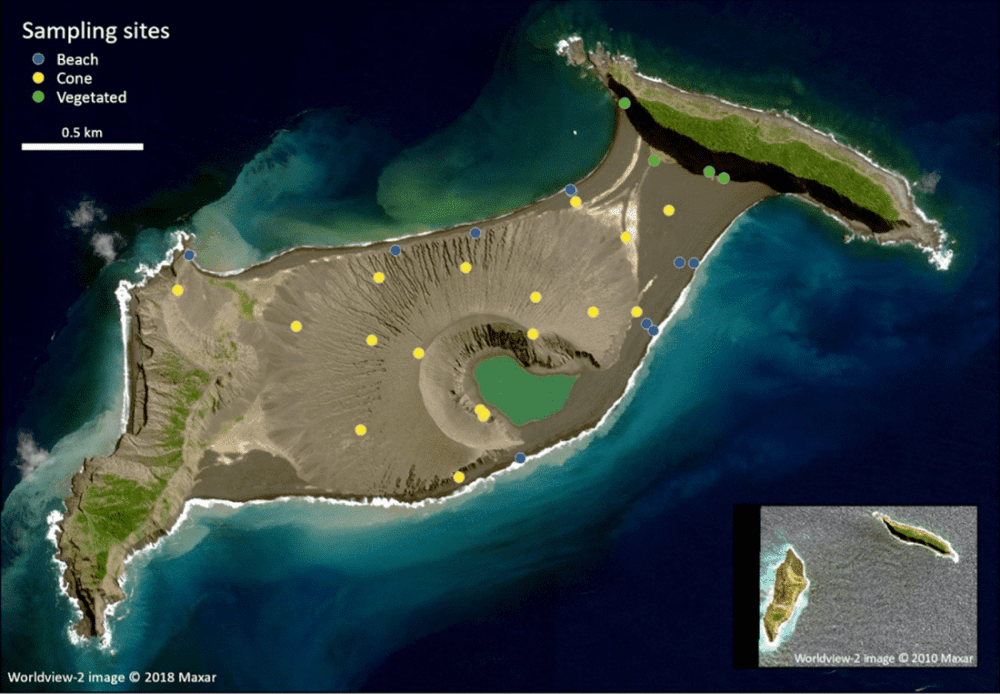

The unique opportunity to study a brand new island gave Dragone and colleagues an “unparalleled natural laboratory” in which to study the earliest stages of the development of an ecosystem, even before plants and animals come into the picture. They were looking for the microscopic island residents, and to find them they took soil samples that were then analyzed using DNA sequencing.

“We didn’t see what we were expecting,” said Dragone. “We thought we’d see organisms you find when a glacier retreats, or cyanobacteria, more typical early colonizer species – but instead we found a unique group of bacteria that metabolize sulfur and atmospheric gases.”

The island’s volcanic origins likely explain the unusual cast of microbes as they like to eat the sulfur and hydrogen sulfide gas that are so common on islands born of eruptions. For this reason, microbial ecosystems often mirror those found in similar places, such as hydrothermal vents, hot springs, and other volcanic regions.

It was an exciting and unique adventure for the team of scientists working on Hunga Tonga Hunga Ha’apai, but it wouldn’t last long. Seven years after it first rose out of the sea, the island was destroyed by the very thing that brought it into being: a volcanic eruption.

The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano that erupted beneath the Pacific Ocean on January 15, 2022, had a blast so strong it launched a colossal plume of water to a height of 53 kilometers (33 miles). The eruption transferred roughly 146 billion kilograms (322 billion pounds) of water into the stratosphere, and destroyed the island that Dragone and colleagues had been working on right up until the catastrophic event.

“We were all expecting the island to stay,” Dragone explained. “In fact, the week before the island exploded we were starting to plan a return trip.”

The team were sorry to see their temporary field site go, but you never know what the future holds when working in volcanically active regions.

“We are of course disappointed that the island is gone, but now we have a lot of predictions about what happens when islands form,” Dragone concluded. “If something formed again, we would love to go there and collect more data. We would have a game plan of how to study it.”

The study was published in mBio.

Source Link: Scientists Were Studying Life On A New Island, Then It Disappeared