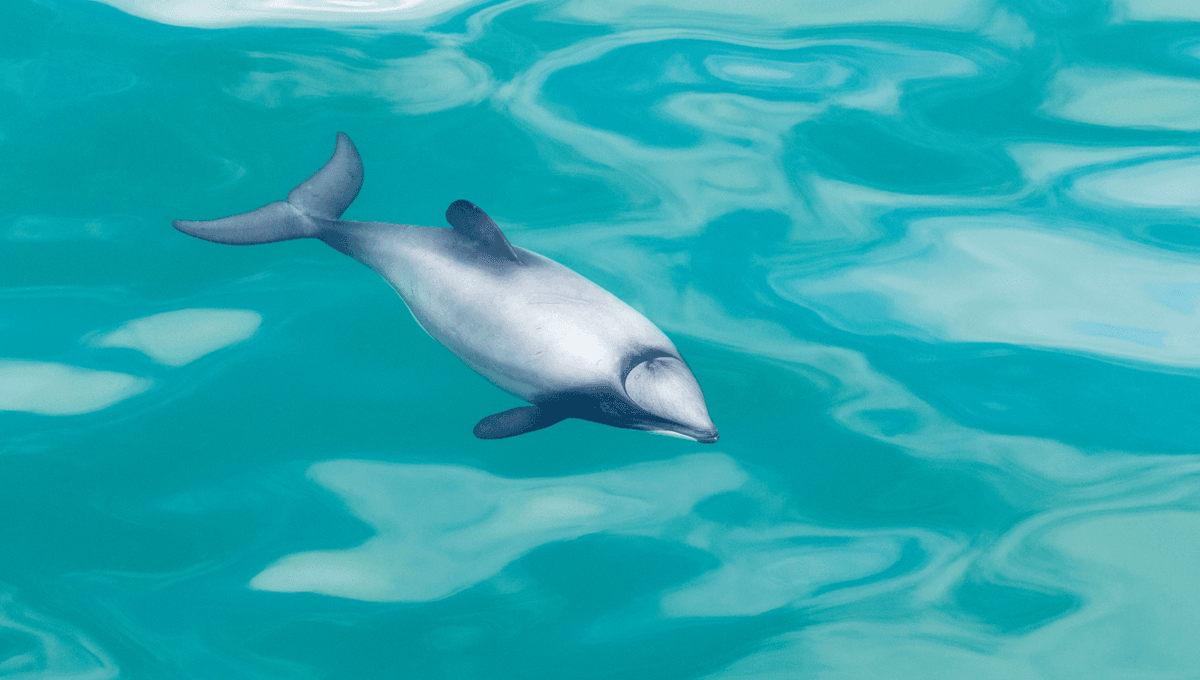

High-tech tags are revealing a side of the Hector’s dolphin the world rarely sees – its showstopping acrobatics beneath New Zealand’s waters.

At just 1.4 meters (4.5 feet) long, Hector’s dolphins (Cephalorhynchus hectori) are the smallest marine dolphins in Earth’s seas. They are not to be confused with other record-holding small cetaceans, like the vaquita, which is technically a porpoise, or the tucuxi, a dolphin that inhabits freshwater.

They’re technically divided into two subspecies: the critically endangered Māui dolphin, found off the coast of the North Island, and the South Island Hector’s dolphin, of which there are around 15,000 individuals left in the wild.

Researchers from the University of Auckland tracked the movements of 11 South Island Hector’s dolphins in Te Koko-o-Kupe/Cloudy Bay using DTAGs, sophisticated devices that are attached to their bodies with a suction cup and record the animals’ slightest motions.

It showed that, below the surface, these tiny cetaceans were experts at performing acrobatic flips, barrel rolls, and dives up to 120 meters (nearly 400 feet) deep.

“There are some seriously impressive dives,” Dr Ilias Foskolos, lead author of the study and biologist at the University of Auckland, said in a statement.

“Swimming down to 120 metres, that’s quite something for a 1.4 metre long animal – it wasn’t what we expected,” Foskolos added.

Much of this behavior was associated with their feeding, with the dolphins switching up their movements depending on where they were hunting for fish. Close to the seabed, they glided at a leisurely pace, rolling onto their backs to snatch up flatfish and cod. Higher up in the mid-water, their movements were more vigorous, using barrel rolls to seize small schooling fish.

Despite their small size, these dolphins cover remarkable distances. One individual was tracked traveling 15 kilometers (9.3 miles) along the South Island’s coast.

The study’s ultimate goal goes beyond capturing their underwater dances. Like many dolphins, Hector’s dolphins are vulnerable to getting entangled in fishing gear, which poses a significant threat to the species’ survival. By understanding their movements and underwater behavior in detail, the researchers hope to design strategies to better protect them.

“Despite this being a preliminary study, we can clearly see the value of the DTAG for understanding risks such as interactions with fishing gear or vessels. It’s important to continue this work to better understand how to minimize the risks to the dolphins and to know how they behave in other locations,” explained Professor Rochelle Constantine from the University of Auckland.

The study is published in the journal Conservation Letters.

Source Link: "Seriously Impressive Dives": World's Smallest Marine Dolphin Is An Expert Underwater Acrobat