JWST has been the star (pun intended) of this year in science, wowing the world with the beauty of its images and forming the basis of an astonishing number of abundant scientific papers, published in record time. When looking at some of the highlights, it’s important to remember it’s only been in orbit for just over a year, and in full operation for half that time.

Possibly the most popular photograph with the public has been the header image for this article, the Carina Nebula. The nebula is a star-forming region officially known as NGC 3324. Stars just starting to fuse hydrogen release a lot of the infrared wavelengths in which JWST operates, and these also penetrate the nebula’s dust well, allowing us to see stars far younger than ever before. The appearance of an escarpment in the walls of the cavity carved out by ultraviolet radiation and stellar winds from powerful stars has earned the nickname the Cosmic Cliffs.

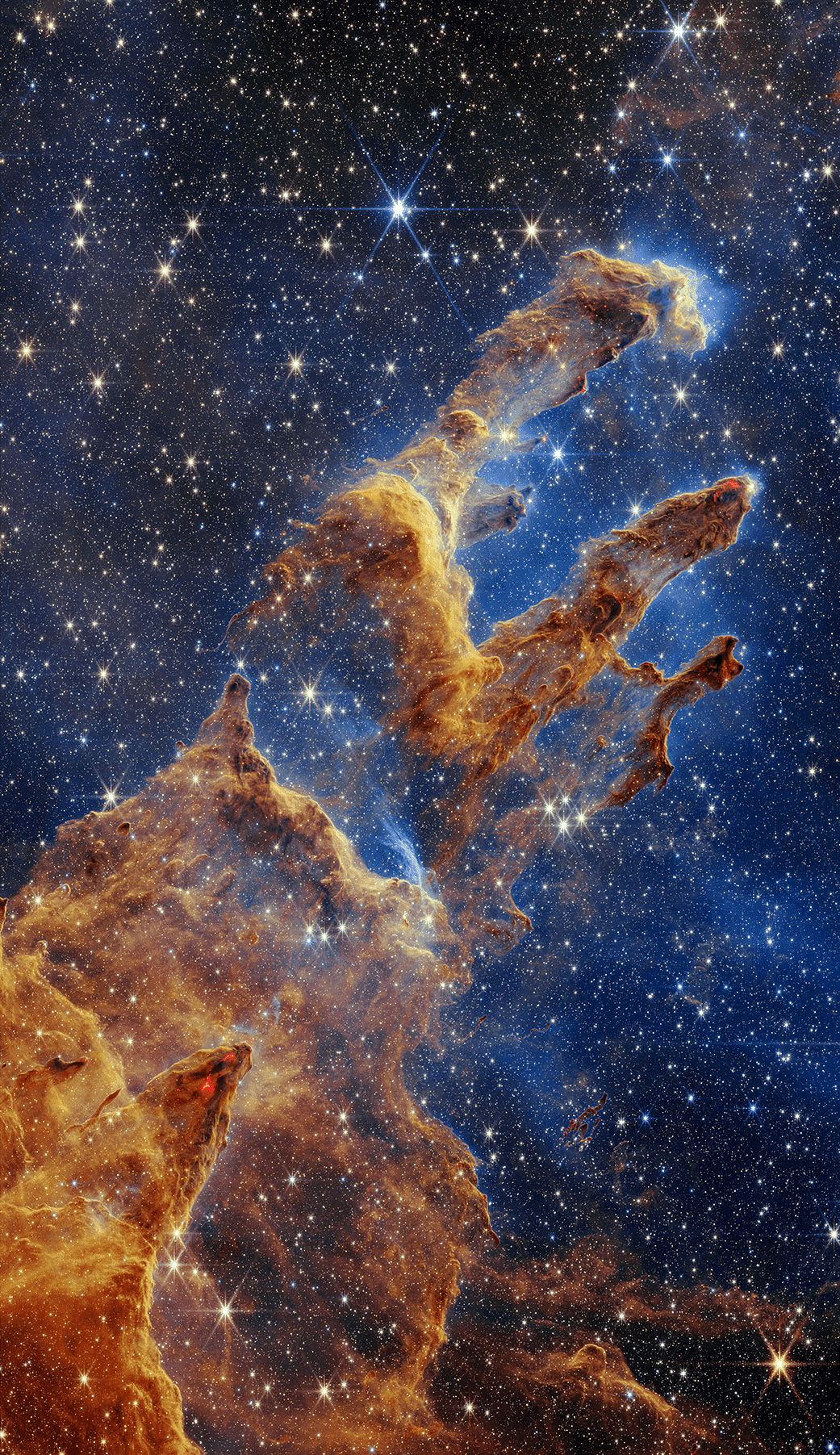

The famous Pillars of Creation provide a similar example of gas clouds being sculpted by stellar winds and radiation to the Carina Nebula. In this case however, it is all set against a background littered with stars, and the gas looks like a hand reaching to capture some of them.

The Pillars of Creation look amazing enough; the stars they seem to be trying to catch add an extra level. Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI; Joseph DePasquale (STScI), Anton M. Koekemoer (STScI), Alyssa Pagan (STScI).

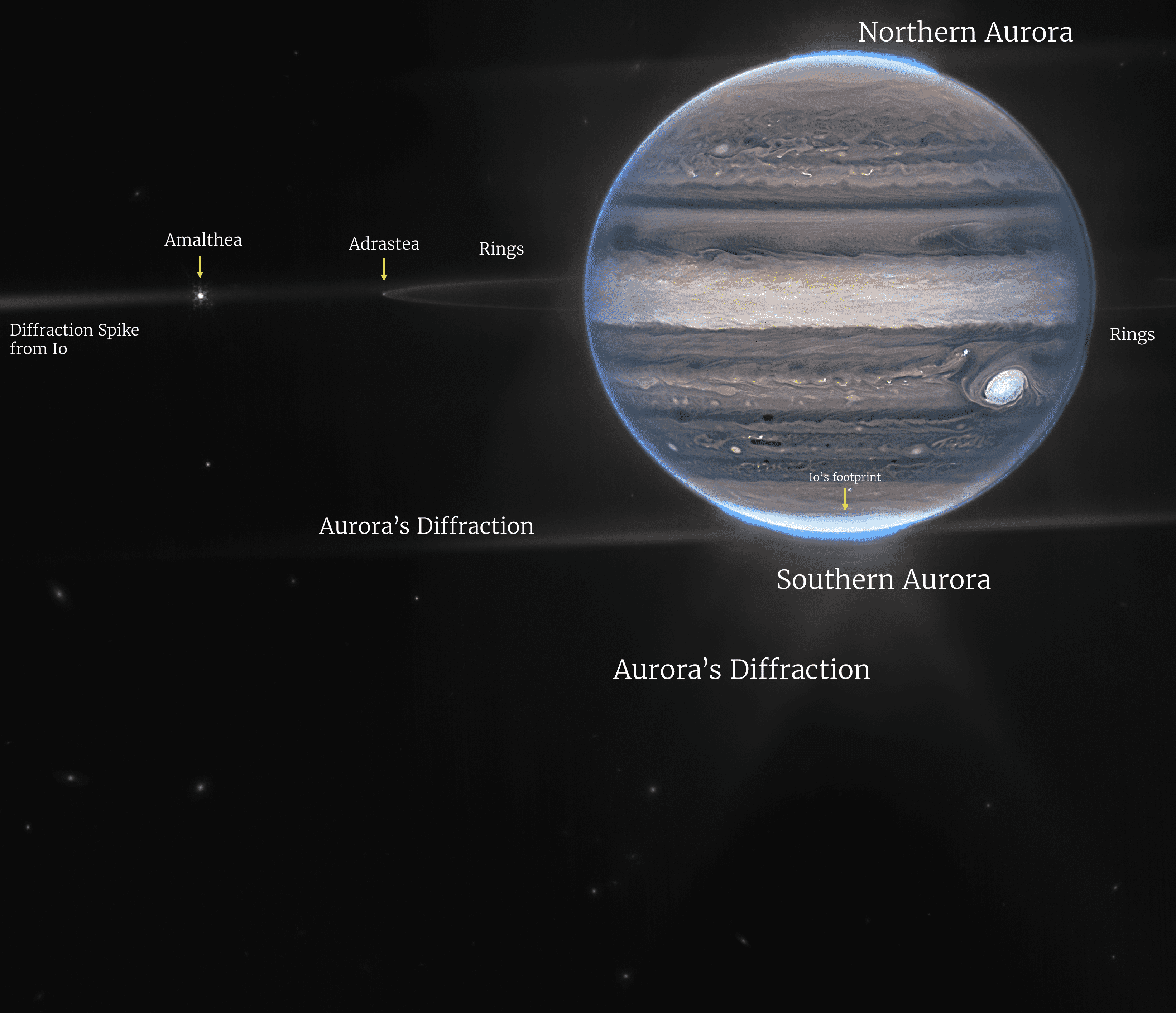

You might think that after four spacecraft had paid a visit to Jupiter, and two have spent years exploring it, the JWST wouldn’t have much to add from a least 600 million kilometers away. However, JWST’s infrared operations and the remarkable instruments it carries enabled us to see the Solar System’s largest planet in a (literally) whole new light. Most of the attention has been on what JWST has revealed about the gas giant’s clouds, but the image below shows it can also give us an exceptional view of the planet’s moons, rings and aurora.

Jupiter in infrared, its aurora, two inner moons, its faint rings and even the diffraction of the aurora. Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Jupiter ERS Team; image processing by Ricardo Hueso (UPV/EHU) and Judy Schmidt

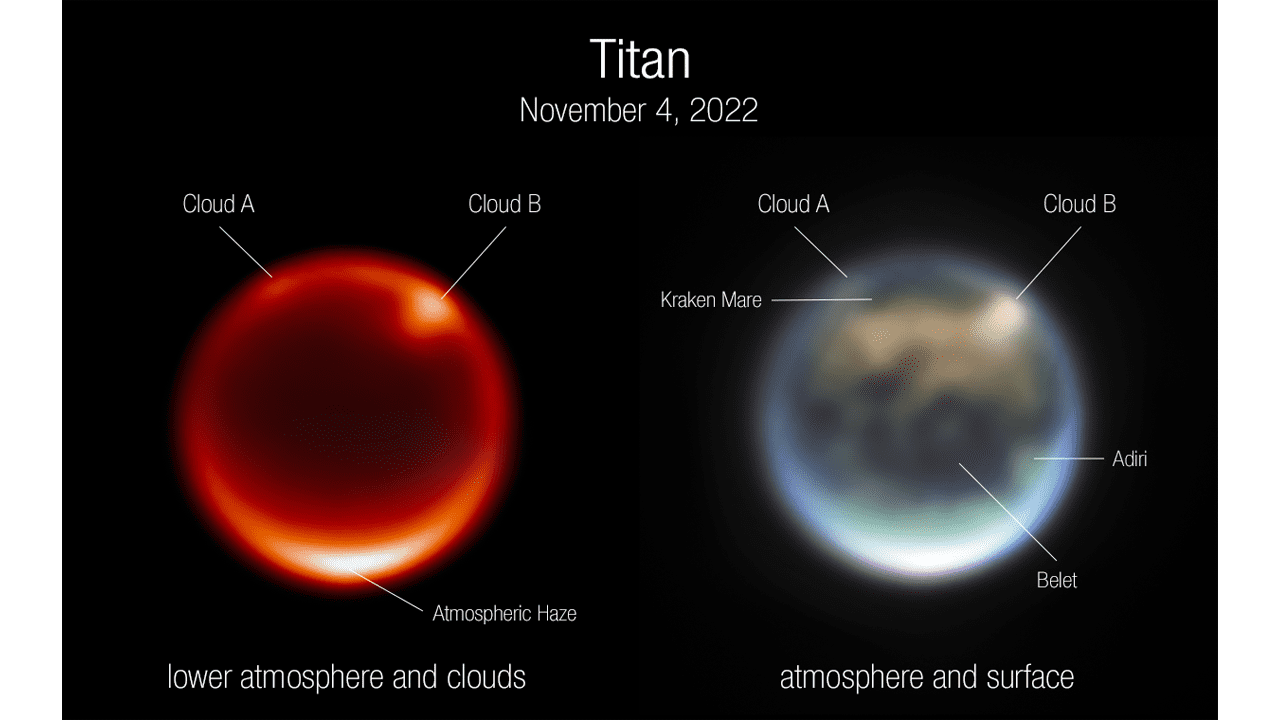

Titan is another world humanity has viewed close up, primarily through the Cassini mission and Huygens Lander. As the only moon in the Solar System with a substantial atmosphere, the giant satellite is set to get its own “Dragonfly” spacecraft, but in the meantime JWST has observed a sea and combined with the Keck Observatory in Hawai’i to record the movements of clouds.

Titan as seen by the JWST’s NIRCam (left) and a composite image on the right. Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, A. Pagan (STScI)

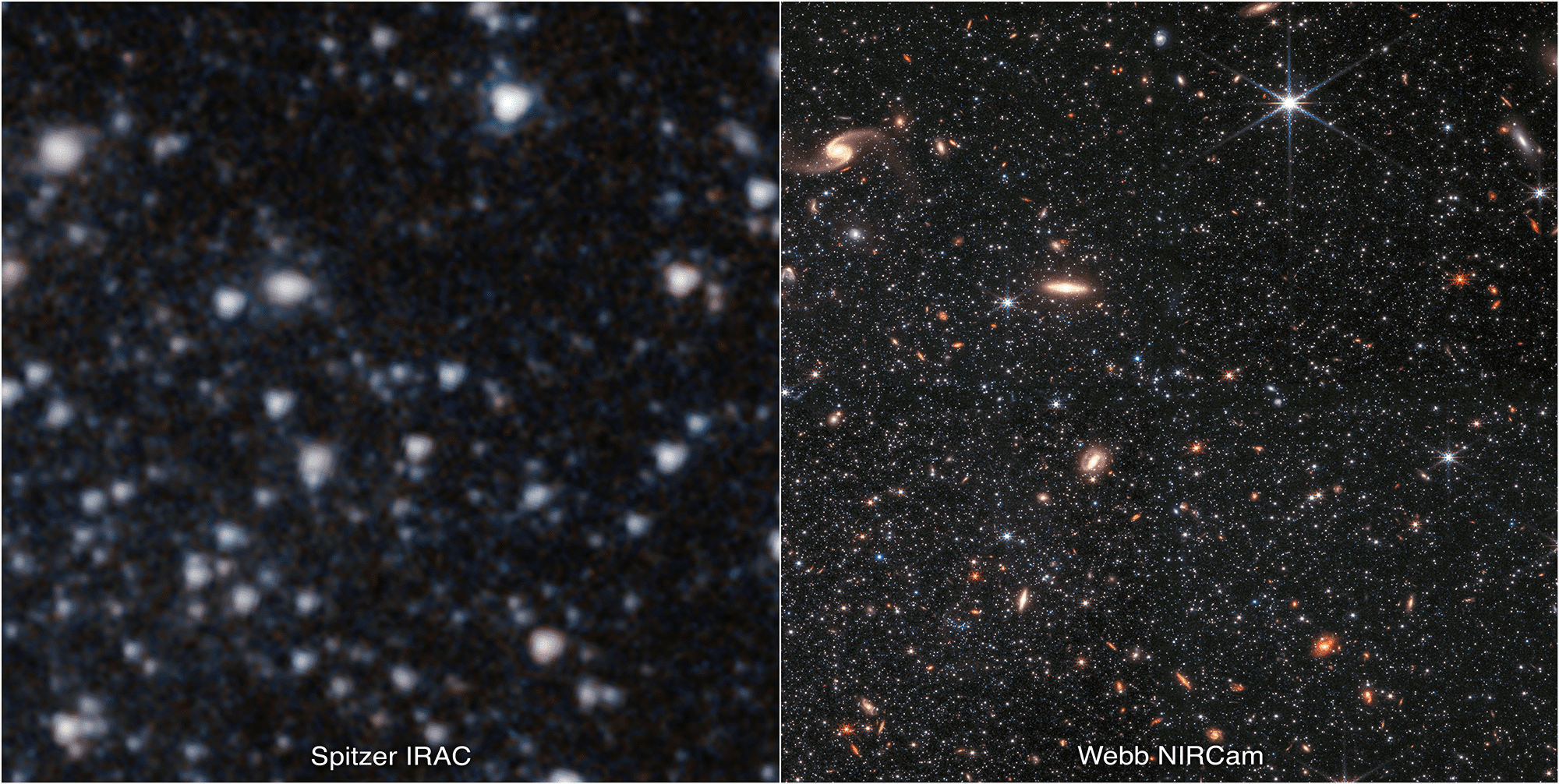

Wolf-Lundmark-Melotte is a dwarf galaxy close enough that JWST can resolve individual stars, a rarity beyond our own galaxy. Despite having a fraction of the Milky Way’s stars, the small galaxy is packed closely enough to provide the stunning view on the right when imaged by the JWST, with the now discontinued Spitzer space telescope’s image of the same field on the left for contrast.

Wolf-Lundmark-Melotte as seen by Spitzer left and JWST right, showing how far infrared astronomy has come. Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, and Kristen McQuinn (Rutgers University). Image processing: Alyssa Pagan (STScI)

Wolf-Rayet stars are a category of extremely hot stars – some with surfaces almost 40 times hotter than the Sun’s. Having lost their outer hydrogen, these stars are now fusing helium or even heavier elements. Wolf-Rayet 140 is a special case, as the star is part of a binary pair. As the two orbit each other, they release dust on an eight-year cycle that looks like tree rings, and performs a similar role in revealing the pair’s history. The rings were already known, and part of the reason the pair were chosen as an early JWST target, but the 3D geometry, and the number of visible shells, amazed the observers.

A helium-burning Wolf-Rayet star in a binary pair with another star releasing dust on an eight year cycle, revealing the system’s history. Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, JPL-Caltech

Sometimes there is a correlation between images being a feast for the eyes and a bonanza for scientists, but that isn’t always the case. The first image the space telescope took of a planet beyond our solar system was described by Dr Sasha Hinkley of the University of Exeter as a “Transformational moment, not only for Webb but also for astronomy generally.” However, it’s not exactly exciting to look at.

For the other extreme, it’s hard to go past Webb’s First Deep Field. There is a reason why President Biden chose to make this the image he released first on July 11, a day before the other four introductory images.

The JWST deep field includes the most distant galaxies we have ever seen, amplified by a powerful gravitational lens. Some of the galaxies are so distant they challenge standard cosmology. Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, and STScI

The field includes the most distant galaxies ever seen, assisted by the gravitational lens provided by foreground galaxies, and as such has launched a flood of papers. However, it is also something everyone, whatever their level of astronomical knowledge, can gaze on for hours, always finding something new.

Source Link: Seven Of JWST’s Best Images From Its First Year In Orbit