Bodies preserved by the deep cold of the Altai mountains offer archaeologists a rare insight into ancient tattoo art, and modern artists are impressed by the skill some of the work displays.

Tattooing is so widespread across cultures that were isolated from each other that it almost certainly has very ancient roots. However, skin is seldom preserved enough to allow us to know which ancient ancestors adopted the practice, let alone see their designs. However, in the Altai mountains, bodies up to 2,000 years old were buried in deep chambers where the permafrost has kept skin, and the ink it carries, intact.

The first detailed exploration of one body preserved by the cold has revealed significant contrasts between the two arms. Either the work on the right forearm was done by a more skilled artist, capable of more subtle and technical work, than the left, or the arms represent the progress of an individual over time.

The authors of a study on the female mummy conclude this means that in the culture of the region, tattooing was a skilled craft, which they suspect required formal training.

The Altai mountains are most famous to science lovers as the location for Denisova Cave, which gave its name to the Denisovans, whose fossils were first found there. Early modern humans and Neanderthals also lived there at times. Long after the Denisovans were gone, tin from the mountains started the Bronze Age culture that spread across much of Eurasia. The mummy studied here, however, is more recent, from the Pazyryks, a subset of the Scythians whose westward migrations had powerful effects on settled populations in Europe and western Asia.

3D models of the mummy from Pazyryk tomb 5 in the visible (A) and infrared (B).

Image Credit: M. Vavulin

“The tattoos of the Pazyryk culture – Iron Age pastoralists of the Altai Mountains – have long intrigued archaeologists due to their elaborate figural designs,” Dr Gino Caspari of the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology said in a statement seen by IFLScience.

Despite the remarkable preservation, the Altai mummies’ skin has usually decayed to the point that tattoos can only be seen under infrared light. Instead of taking detailed images of the tattoos, early studies made monochrome drawings, sometimes just schematics, which limited what could be learned.

“Prior scholarship focused primarily on the stylistic and symbolic dimensions of these tattoos, with data derived largely from hand-drawn reconstructions,” Caspari said. “These interpretations lacked clarity regarding the techniques and tools used and did not focus much on the individuals but rather the overarching social context.”

New research goes to the opposite extreme, making a 3D scan of one Pazyryk mummy using digital near-infrared photography. Caspari and co-authors then consulted a modern tattoo artist for an assessment of the work and what would have been required to make it.

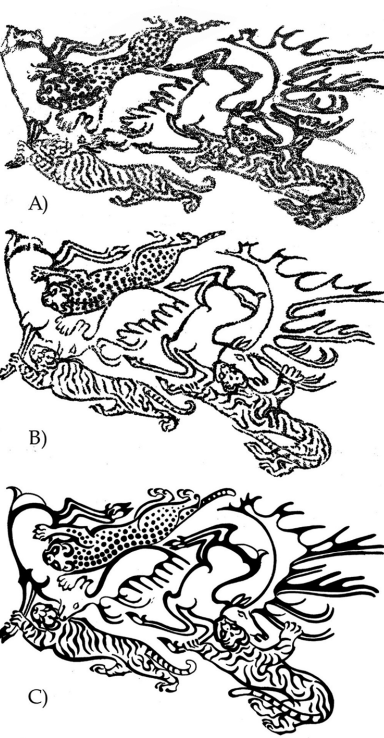

The authors consider the work on the left arm to have either been hurried or made by someone relatively unskilled. On the other hand, the right arm and hand appear to have been marked with great care and skill over at least two sessions. The artist fitted drawings of cats, a rooster, and two deer or other ungulates to the natural shape of the body. Some of the effects would be hard to achieve even by professional tattooists using modern equipment, raising questions about what tools Pazyryk tattooists used.

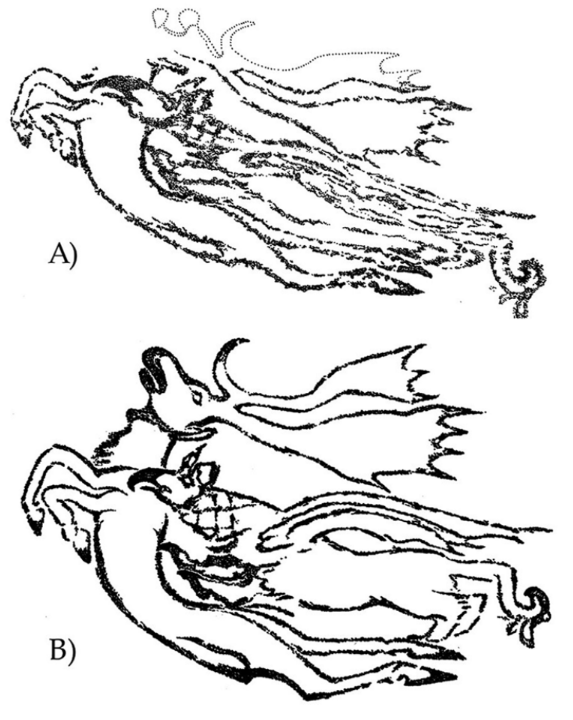

The current state of a drawing on the left forearm (A) and a reconstruction of its original state correcting for dessication (B).

Image Credit: D. Riday

“The interpretation of tattoos in prehistoric contexts necessarily remains speculative and may never reach the intricate richness of meaning with which the images and practices were originally associated,” the authors write. Nevertheless, they think there is still plenty we can learn.

The current state of the right forearm tattoo (A); it’s likely original state correcting for dessication (B); and an idealised drawing of the same picture (C).

Image Credit: D. Riday

“The study offers a new way to recognize personal agency in prehistoric body modification practices,” Caspari said. “Tattooing emerges not merely as symbolic decoration but as a specialized craft – one that demanded technical skill, aesthetic sensitivity, and formal training or apprenticeship.”

“This made me feel like we were much closer to seeing the people behind the art, how they worked and learned and made mistakes,” Caspari concluded. “The images came alive.”

The study is published in Antiquity.

Source Link: Siberian Mummy's 2,000-Year-Old Tattoos Reveal The History Of Ancient Art