Higher intelligence is not only a way to increase survival rates, it could also improve reproductive success, at least among male mosquitofish (Gambusia holbrooki). The finding doesn’t prove the popular hypothesis that human intelligence is a product of needing to impress mates, but it does show something analogous may have occurred on a vastly smaller scale.

ADVERTISEMENT

There are obvious benefits to intelligence, helping animals find food or increasing the chance of avoiding predators, either of which will improve survival. It’s particularly important in social species that need to communicate and get along. Nevertheless, brains are also very energy-intensive, and sometimes it is hard to work out how having extra smarts justifies its cost. That’s particularly the case in the long period between humans reaching our current intelligence, and when we started inventing the tools that gave us large survival advantages. Maybe impressing potential partners was the spur.

One way to shed light on that is to look at whether intelligence provides a reproductive advantage in species that are easier to study. Their small size and swift reproductive cycle mean mosquitofish form a particularly good study subject, so Dr Ivan Vinogradov of the Australian National University and colleagues sought to eliminate survival advantages for smart mosquitofish to see if they still had more offspring.

The easy part was creating predator-free ponds and ensuring no mosquitofish went hungry. More of a challenge was testing the subjects’ intelligence.

Our study suggests that intelligence in mosquitofish isn’t only driven by their need to find food or avoid predators, but also by the complex challenges of finding love

Ivan Vinogradov

Rather than assume a single universal mosquitofish intelligence, Vinogradov and colleagues put all 30 males in their study through four tests covering self-control, spatial learning, associative learning, and reversal learning.

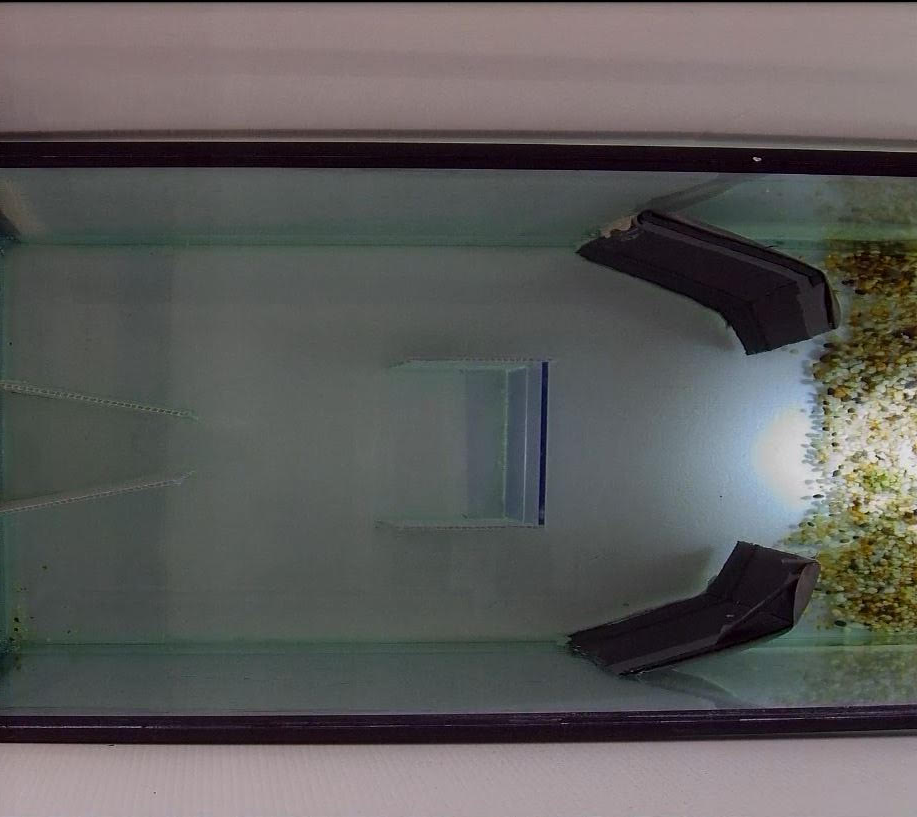

The first test investigated whether a male would swim around a transparent barrier to get to a female, or keep trying to go through; while the second required them to find their way through a maze. The third and fourth were linked: first seeing how quickly they came to associate a particular color with a food reward, and then how quickly they adapted when the color’s meaning changed.

The setup for the first test, where males had to learn to go around the transparent screen, rather than trying to go through.

Image Credit: David Fanner, courtesy of Ivan Vinogradov

“A secondary goal of the study is to look at general intelligence,” Vinogradov, lead author of the study, told IFLScience. The team hoped to see whether being strong in one form of intelligence was highly correlated with performance in others, or if it was common to be specialized. Once again, this echoes a long-running debate regarding human intelligence.

It turns out correlations were very low – other than between associative and reversal learning – suggesting mosquitofish are not given to a consistent general intelligence, and the decision to run several tests was the right one.

The maze the males had to find their way through to score high on the test wasn’t all that complex, but these are fish.

Image Credit: David Fanner, courtesy of Ivan Vinogradov

Mosquitofish mate very frequently, and it is common for a single brood to have multiple fathers. The team genetically tested all 2,430 offspring in the 11 ponds after 20 days and found that males who scored high for self-control and spatial learning had many more offspring. Scoring high for other forms of intelligence, as well as body size and boldness, was also associated with more offspring, but not to a statistically significant extent.

Vinogradov told IFLScience that the team could think of three possibilities for that observation, given the fish were not using these skills to evade predators.

ADVERTISEMENT

Mosquitofish don’t really get the whole consent thing, with males often harassing females into mating, or sneaking up on them. Consequently, Vinogradov told IFLScience; “It’s possible these skills make males better at one approach or the other. Alternatively, females may exercise some choice that isn’t obvious to us.” Perhaps the females are keeping an eye on the males, and accepting the advances of males who have displayed these forms of intelligence.

“The third possibility is there is some connection between brain and overall body conditions, so perhaps the smart fish are faster because of better body condition,” told IFLScience. “Intelligence could be secondary.”

More studies could tease some of these questions out.

“This suggests that intelligence in mosquitofish partly evolved through sexual selection, where traits that boost mating and fertilization success become more common over generations. Sexual selection is usually stronger in males than females because in most species there are more males seeking mates than females ready to mate and breed,” said in a statement.

ADVERTISEMENT

Optimistically he added; “Our study suggests that intelligence in mosquitofish isn’t only driven by their need to find food or avoid predators, but also by the complex challenges of finding love. This shows that, much like humans, love conquers all.”

Vinogradov’s second explanation has been shown to apply in budgerigars, where females want to get close to males who demonstrate problem-solving skills. “There are lots of studies that investigate intelligence and reproductive success,” Vinogradov said. “They’re mostly focussed on birds and show more intelligent birds lay more eggs.” Few have followed through to see how many of these eggs survive, something Vinogradov said is much harder. Vinogradov’s team skipped that step by genetically testing the entire population of the pond.

Vinogradov didn’t want to be drawn into the debate about human intelligence, other than to say his team’s work; “Does show a mechanism for sexual selection is possible.” Mosquitofish were specifically chosen because many complicating factors that would confuse the connection in species closer to us, such as parental care, were not relevant.

The study is published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

Source Link: Smart Is Sexy: More Intelligent Mosquitofish Males Sire More Offspring