There is something magical about the flight of the swift. They are quick, almost too quick for us to see. Here one moment, the next they are gone, always chasing bugs. Unlike us land animals leaving footprints with every step, each wingbeat leaves no trace of its passage. That is until Xavi Bou started capturing and collecting them. Overlaying every second of their movement he showed us that their flight was far from erratic. It was a beautiful dance in the skies.

After a career in advertising and fashion post-production, Xavi Bou started applying his keen aesthetic sense to something he valued and was truly passionate about: mesmerizing us with the beauty of nature in a new way. A way we can’t quite capture with our own eyes. “My challenge is trying to find this hidden beauty behind these natural movements,” said Bou to IFLScience.

We live in a changing landscape, people becoming “more conscious about equality, about environmental things.” Bou believes that the way we look at the world is shifting and that that same shift needs to happen in the arts. That there is not a single version of reality, and if you “only show the reality in one way you are missing many.”

For example, we know that we can only see in the visible spectrum of light, yet we also know that the world is full of color in infrared and ultraviolet. Bou wants to remind us of this invisible complexity, encouraging us to be open-minded in our perception of reality.

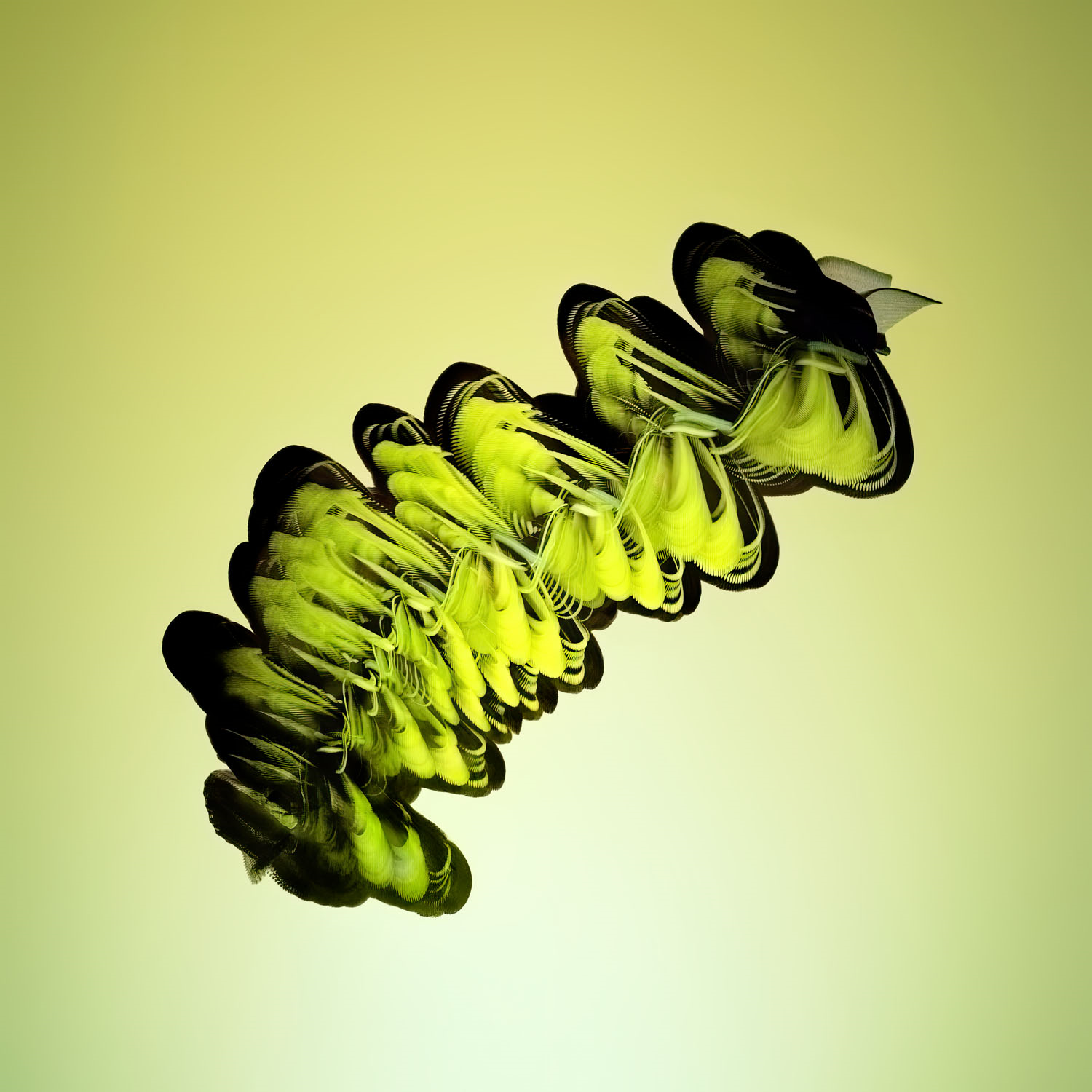

The alpine swift (Tachymarptis melba) soars over the Medes Islands in Catalonia, 2023.

Image courtesy of Xavi Bou

A natural connection

Stop. Hidden among the chatter of people in the streets and rumble of the traffic, do you hear the singing of the birds? Look up. Past the cornices of the buildings, among the leaves of the trees, do you see the flight of birds?

We have lost our connection to the natural world, making us blind to the nature around us, to the birds. Bou’s goal is for people to leave an exhibition of his work with a renewed sense of wonder. “Many people came up after […] and say, ‘Oh, since I have been in the exhibition I have been more paying attention with birds’. And for me it’s a first step. Get reconnected,” he told IFLScience.

In his eyes, our human ability to empathize with other humans, to feel their suffering even a world apart, and our ability to empathize and care for nature makes us amazing creatures: “It’s the first time in human history that people care about nature, because now it’s not just food and danger.”

This is offering an opportunity to rekindle our relationship with nature, which can add an “extra layer of happiness” to our experience of the world. Being in a forest (or even a park) is amazing and spectacular all on its own, but for Bou knowing there is a bird, maybe a great owl, in this forest gives the experience a layer of possibility, enhancing it with excitement.

A complex choreography

After a lifetime of birdwatching, it was natural for birds to be the muse of Bou’s art: “The goal of the project was never to make a collection of different types of species. It is more looking at this complex behavior.”

For eight years, Bou studied birds by capturing the choreography of their flight and wingbeat patterns. He called them Ornithographies. Different species offered different opportunities. Sometimes many species share a similar behavior. For example, the passerines (think sparrows and tits) have a common aesthetic: “flapping the wings or flapping and closing, flapping and closing,” going from one point to another.

Other species can offer a more diverse range of flight patterns, like “seagulls could do flapping or gliding, or sometimes they fly together low, doing […] tornado shapes.” The swifts, residents of the sky, dash about when feeding and then fly in circles before sleep. All these behaviors are different and unpredictable and “will become a different type of drawing in the sky,” said Bou. “I love the unpredictable thing.”

Each drawing dazzles us with its poetry, opening a window into the life of the bird.

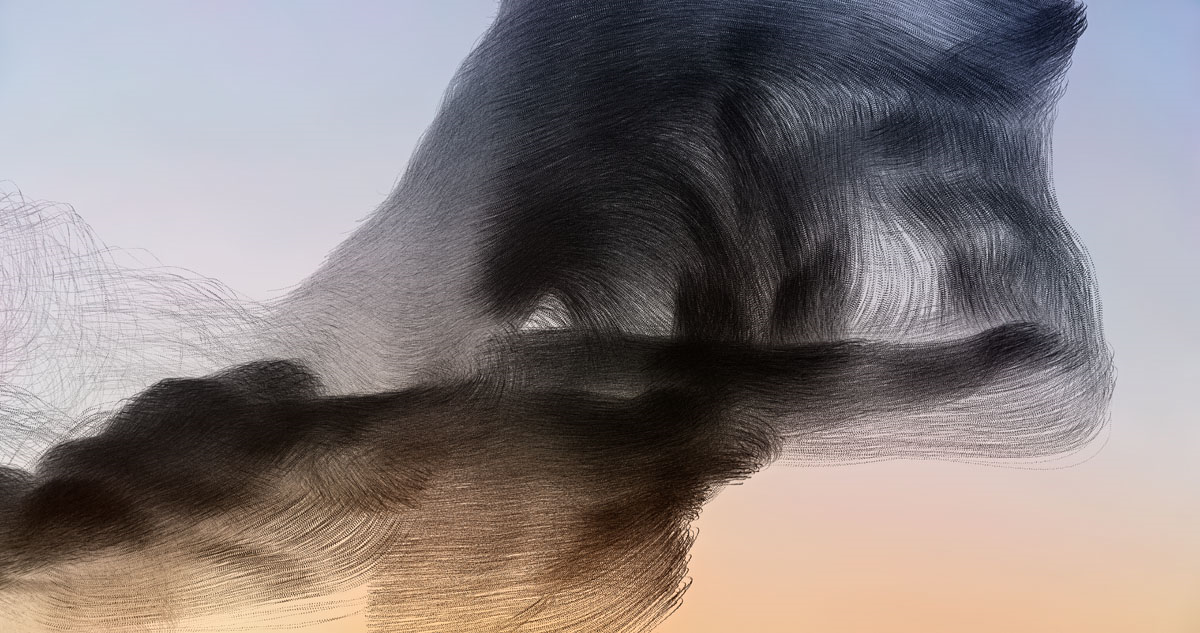

The red kite (Milvus milvus) flapping and gliding in Lleida (Catalonia), 2023.

Image courtesy of Xavi Bou

Bou himself is the curator, identifying the best moment and place to capture the most interesting image. It requires a deep knowledge of the bird world. “When you work with nature, it’s important to have as much information as possible to succeed, because there are many chances that the birds are not there or are not doing what you want,” Bou told IFLScience. The success of this project hinged on a lifelong passion for birds.

His life became about following the birds, synchronizing his calendar with theirs. The swifts have just left his hometown of Barcelona, but “in two weeks in Tarifa will be hundreds or thousands of kites, black kites flying towards the wind to Africa. […] In two weeks more the storks, and in November will begin the starling.” The rhythm of nature.

To improve his chances, he would get some intel from ornithologists, learn from them about where to find the birds, but then, in the field, he was always alone. Until now.

Birds, bugs, and beyond

“After some years I think […] maybe I’m missing some interesting other natural movements like insects. So I decided, like three years ago, to expand this vision to other animal groups. I begin with the insect. […] Now, I’m also researching […] plankton fishes. And well, my goal is [to] mix these different scales. […] to put a plankton next to a vulture, or next to beetle flight.”

Oak treehopper (Platycotis vittata) and green treehopper (Archasia belfragei) hopping into flight, filmed at 4,000 frames per second.

Image courtesy of Xavi Bou

His expanding curiosity has put him out of his comfort zone, working with species he is not as familiar with and facing new technical difficulties. It’s an interesting time for Bou as he is now working with entomologists and marine biologists, bringing his art closer to science in these collaborations.

“It’s a new world for me. So without [the scientists] I could not even say the [name] of the plankton, but I’m beginning to study that also. I’m reading books about insects because it’s good to know.” An artist of nature, like a scientist, requires knowledge. Knowledge about behaviors, and knowledge about how to capture them.

The technical inspiration for Bou’s work came from chronophotography, the technique pioneered by Eadweard Muybridge that first showed us the sequence of strides of a galloping horse and that physiologist Étienne-Jules Marey used to study animal movement. The Ornithographies were made by filming birds at 60 frames per second and then in post-production superimposing the images to reveal their tracks. Bird wingbeat frequencies range from 2 to 100 Hz, so most bird flights can be captured at 60 Hz.

Insects, on the other hand, can beat their wings hundreds of times per second, with some mosquitos reaching 800 Hz. The elegant intricacies of each wingbeat can’t be captured, unless you are using cameras recording at 1,000-5,000 frames per second.

Dr Adrian Smith is an entomologist and Research Assistant Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at North Carolina State University. He is passionate about filming insect flight and shares his footage on his YouTube channel. Dr Smith had already solved a lot of the challenges Bou was facing: good cameras, good lighting, knowledge about how to handle insects and get them to fly. In fact, he has already made the footage that Bou wants.

The Entomographies were born out of this collaboration. “His goal as an artist and my goal as a scientist are really the same in that we both want to give people a new way to see and appreciate the natural world,” said Dr Smith in a YouTube short. In the flurry of fanning wings, the insects disappear into their flight.

Zebra longwing (Heliconius charithonia) in a flurry of wings, filmed at 1,500 frames per second.

Image courtesy of Xavi Bou

Bou is collaborating even more closely with scientists to capture the swirls of swimming plankton. Now, he’s actually in the lab, facing a whole new set of challenges. It’s a tricky balance to be able to get good magnification to see the plankton, but also a field of view that is wide enough to capture the range of motion. He has to come up with a new approach. “When you are doing something that could be new, the technology, it’s not created for that purpose,” he told IFLScience. “So yeah, it’s normal that you have some challenges.”

Need for change

Through the dance of swifts and butterflies and plankton, Bou wants to awaken our child-like wonder for nature. This is especially pressing in our current world with its changing climate. The hottest day, an extinct species, devastating hurricanes – catastrophic messages and images are disheartening. And sadness, according to Bou, doesn’t move us to action.

Love, on the other hand, makes us feel like we need to change things, but “we cannot love enough, or get empathy with things that we don’t know, or are too far. For example, with a rare frog of Costa Rica. Okay, I will feel pity if it gets extinct. But my limit of action will be really reduced. So why not start to act locally?”

Nature surrounds us, it even pervades our urban environments. Bou’s beloved swift is the emblem of this. They fill the skies of Barcelona from April to July, but not enough people are looking up. One of his goals is to open our eyes again to the flight of the swift, to feel their presence – and their absence if they were not there. What if we discover we lost something we didn’t care about until it was too late?

Because of increased awareness for the importance and beauty of the swift, “the city council of Barcelona is taking real attention”. When they are “renewing an old building, [they are] not doing it during the nesting time.”

Common starling (Sturnus vulgaris) swarming over Emporda (Catalonia), 2019.

Image courtesy of Xavi Bou

Recent research showed that local conservation actions like habitat protection and restoration are among effective measures in combating the global loss of biodiversity. And it could all start with seeing birds in a new way.

Source Link: Soaring Birds, Buzzing Bugs – Art And Science Capture The “Hidden Beauty” Of Flight