The Sun is constantly spewing solar wind, a stream of charged particles, into interplanetary space. Occasionally, it bursts through in waves that can slam into planets. Geomagnetic storms happen when they hit Earth, for example. Observations of Jupiter from 2017 have now revealed some major changes around the largest planet in the Solar System.

Jupiter’s magnetosphere is enormous, the largest continuous structure in the Solar System apart from the heliosphere itself. It extends 7 million kilometers (4.35 million miles) in a Sunward direction and almost to the orbit of Saturn away from the Sun. The magnetosphere of Jupiter is 10 times stronger than Earth’s own, but even the mighty are affected by the solar waves.

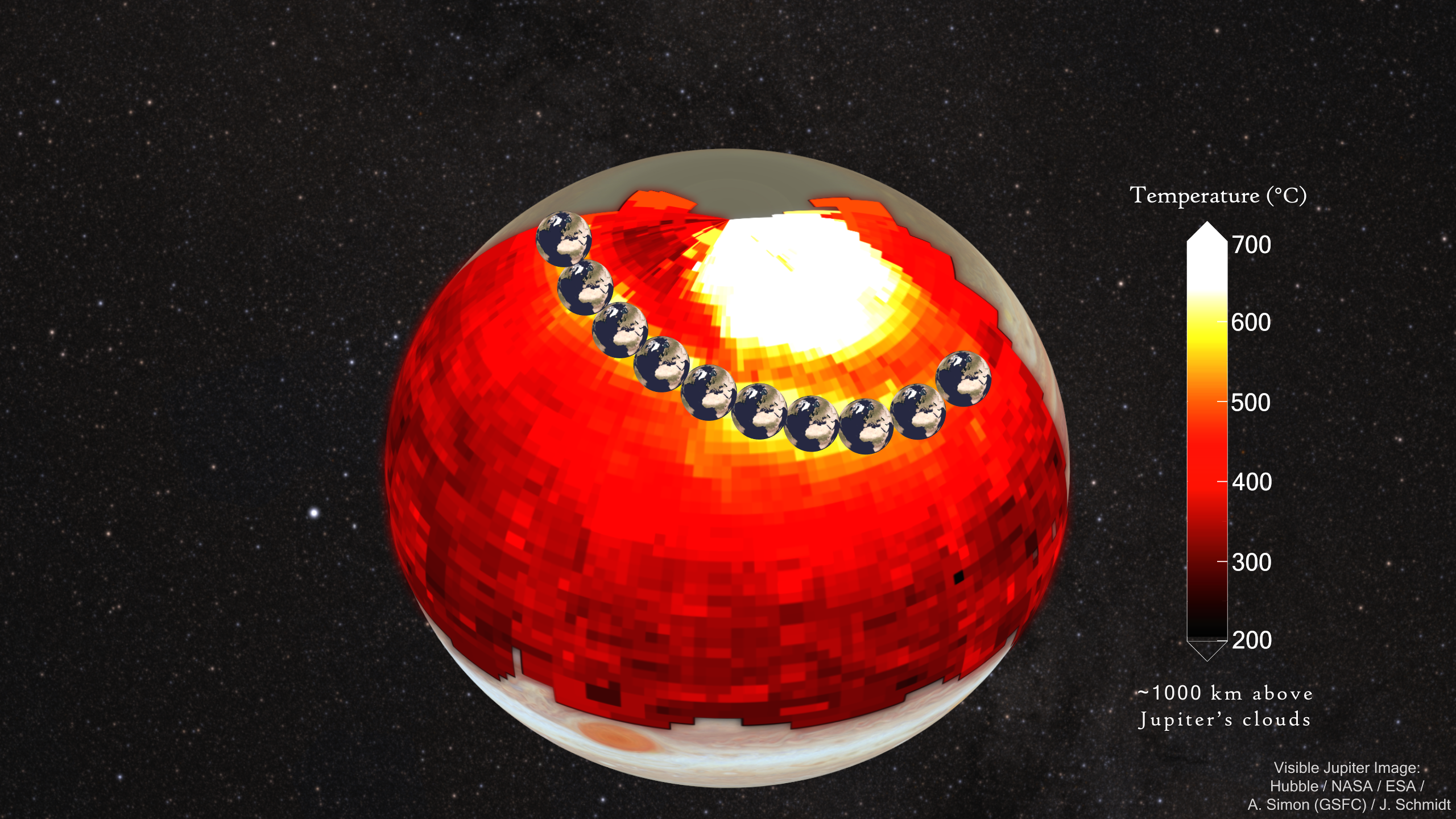

The wave that hit the planet in 2017 compressed this magnetic shield. It created a hot region spanning half of the planet’s circumference with a temperature over 500°C (932°F), much higher than the standard 350°C (662°F) the atmosphere is usually at.

“The solar wind squished Jupiter’s magnetic shield like a giant squash ball. This created a super-hot region that spans half the planet. Jupiter’s diameter is 11 times larger than Earth’s, meaning this heated region is enormous,” lead author Dr James O’Donoghue, from the University of Reading, said in an emailed statement.

The heated region moving towards the equator could easily fit 11 of our planets.

Image credit: Dr James O’Donoghue, University of Reading.

“We’ve studied Jupiter, Saturn and Uranus in increasing detail over the past decade. These giant planets are not as resistant to the Sun’s influence as we thought – they’re vulnerable, like Earth. Jupiter acts like a laboratory, allowing us to study how the Sun affects planets in general. By watching what happens there, we can better predict and understand the effects of solar storms which might disrupt GPS, communications, and power grids on Earth.”

The analysis combined observations from the Keck telescope on Earth and NASA’s Juno mission around Jupiter. Together with solar wind modeling, the team was able to assess how the enormous magnetosphere was compressed.

Researchers believe that the compression intensified the already powerful aurora heat in the polar regions – Jupiter’s aurorae shine in ultraviolet and X-rays – causing the upper atmosphere to expand. This process spilled hot gas towards the equator. These events are expected to happen twice or three times a month. The work has applications not just for astronomy but also for keeping an eye on space weather closer to home.

“Our solar wind model correctly predicted when Jupiter’s atmosphere would be disturbed. This helps us further understand the accuracy of our forecasting systems, which is essential for protecting Earth from dangerous space weather,” Professor Mathew Owens, a co-author also from the University of Reading, added.

The study is published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Source Link: Solar Waves Squash And Massively Heat Up Jupiter’s Magnetic Field 2-3 Times A Month