Many languages talk about the future in ways that are strikingly different from English. And whether we notice it or not, those differences may shape or reflect how we think, how we behave, and even the choices we make every day.

In English, there’s a hard future tense that marks what lies ahead, clearly separating it from the present: we say “It will rain tomorrow.” Many other languages lack such a clear-cut distinction, or at least have a much hazier distinction between now and what comes next.

In many other European languages, there is an optional element when referring to a future-time reference. For example, in German, you could use a future tense by saying “Es wird morgen regnen” (“It will rain tomorrow”). However, in day-to-day conversation, many German speakers just use the present tense with a time marker by saying “Morgen regnet es” (“Tomorrow it rains”). In this instance, the future is expressed without the need for a grammatical future tense.

It might seem like a tiny grammatical detail, but the choice of words carries weight. Saying “Tomorrow it rains”, as opposed to “It will rain tomorrow”, doesn’t merely swap one tense for another; it blurs the boundary between present and future. The event is spoken of as if it’s part of what is already unfolding, and that looser boundary subtly changes the way time itself is framed.

Other languages with a “weak” distinction between the past and future are Norwegian, Danish, Swedish, Dutch, Estonian, and Finnish. In Mandarin Chinese, there’s no dedicated future tense. Instead, the present tense is used with adverbs or context. When speaking about the weather forecast, speakers will say something that basically translates to “Tomorrow rain”.

Remarkably, these grammatical quirks don’t just change how we talk; they may change or reflect how we think and act. Speakers of languages that do not have a strong future tense tend to make more future-oriented choices. For those individuals, it is as if the future feels closer; it is not seen as a distant, abstract concept. In other words, if your language treats the future as part of the present, you’re slightly more likely to act as if tomorrow matters today.

In 2013, Keith Chen, a behavioral economist at the Yale School of Management, carried out a study where he assessed how speakers of different languages face future-oriented decisions. To make more accurate comparisons, he studied individuals who had very similar levels of income, education, family structure, and country of birth, but who spoke different languages within the same country.

The finding showed that people whose languages blur the line between present and future were strikingly more future-minded in their behavior. Compared to speakers of languages that sharply separate today from tomorrow, they were 31 percent more likely to save money in any given year, entered retirement with 39 percent more wealth, were 24 percent less likely to smoke, 29 percent more likely to stay physically active, and 13 percent less likely to be obese.

However, the nature of this relationship isn’t totally clear. Chen writes in the conclusion of the paper: “One important issue in interpreting these results is the possibility that language is not causing but rather reflecting deeper differences that drive savings behavior.”

“Self-reported measures of savings as a cultural value appear to drive savings behavior, yet are completely uncorrelated with the effect of language on savings. That is to say, while both language and cultural values appear to drive savings behavior, these measured effects do not appear to interact with each other in a way you would expect if they were both markers of some common causal factor,” he wrote.

“Nevertheless, the possibility that language acts only as a powerful marker of some deeper driver of intertemporal preferences cannot be completely ruled out,” he concludes.

This is only one way language may shape our sense of space and time. Other studies have shown that people who use a written system arranged from left to right – like English and many other European languages – tend to lay out time as proceeding from left to right when thinking abstractly. Conversely, people who use languages from right to left – like Arabic, Hebrew, and others – arrange time from right to left.

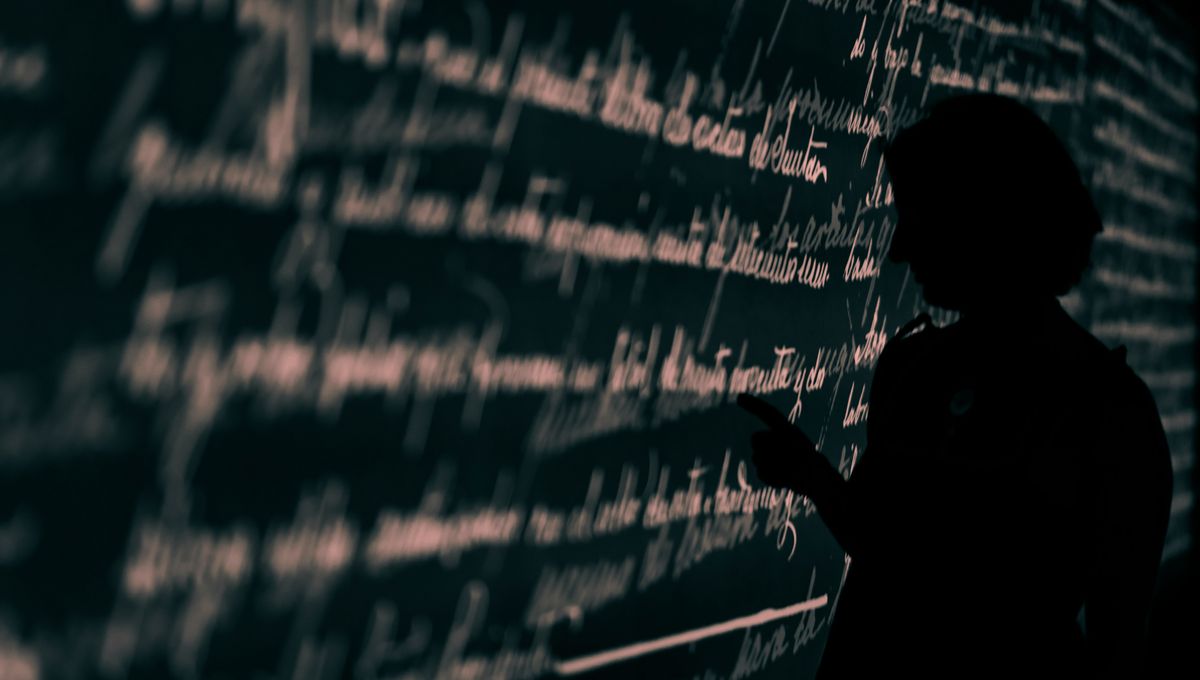

It’s not always easy to appreciate when chatting away or typing a message on screen, but language is a hidden force shaping how we experience reality. Exploring ideas like these is a good way to challenge your preconceptions and remind yourself that your way of seeing the world isn’t set in stone.

Source Link: Some Languages Don't Clearly Express A Sense Of The Future, And It Skews The Way We See Reality