Distributing seeds is among plants’ key challenges, and many have turned to animals for help. However, some get over-reliant on a single species or a few similar ones, with dire consequences when these go extinct. A live demonstration is happening in the biodiversity hotspot of Central Chile where plants with fruits that were once distributed by mastodons are becoming isolated and endangered.

It’s easy for a plant to drop its seeds beneath its canopy, but that’s no path to claiming new territory. A wide variety of plants have discovered that animals are deeply susceptible to bribery, and can be induced to carry seeds a long way if the wrapping tastes good enough.

Big animals are particularly advantageous for these purposes, because they travel further, so some plants have specialized in enticing them by making very hefty fruit. Unfortunately, big animals are rarer and more prone to going extinct, as happened to some of the Americas’ chonkiest animals about 10,000 years ago, either because of climate change or human arrival.

There is a widespread belief that avocados were once distributed by ground sloths and were only rescued from extinction by humans. It now seems more likely that avocados as we know them are the product of agricultural selection. Nevertheless, the basic idea is sound, even if avocados may be a bad example.

The hypothesis was proposed in 1982 to explain the many large fruits in South and Central America that appear to lack a means of dispersal, unless humans take a liking to them.

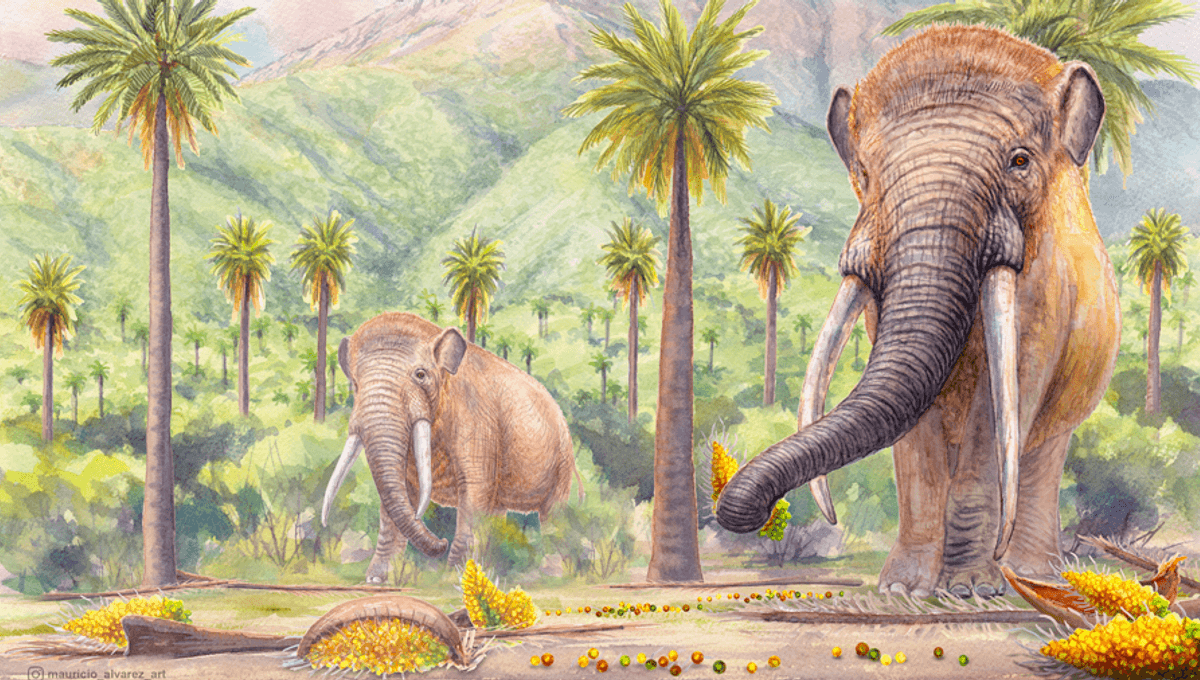

For the idea to be true, some of the large extinct species of the region needed to have been fruit eaters (frugivores) and this has remained uncertain for at least some of the largest examples. However, a new study looking at teeth proves Notiomastodon platensis, a Pleistocene mastodon, was indeed an occasional frugivore.

“We found starch residues and plant tissues typical of fleshy fruits, such as those of the Chilean palm (Jubaea chilensis),” said Professor Florent Rivals of Centres de Recerca de Catalunya in a statement. Anything eating that much fruit would have been moving the seeds around, particularly if they passed through the digestive system first, giving the beast plenty of time to get places.

Fruits have different ratios of isotopes than grasses or leaves, and these are recorded in the teeth and bones of the animal that consumes them. Certain elements can also be matched to their geographic source. “Dental chemistry gives us a direct window into the past,” said Dr Carlos Tornero.

Data from 96 mastodon teeth reveals that the proboscidean lived in fruit-rich forests and traveled widely. Although they mostly fed on leaves, fruit was part of their diet, although more in some regions than others.

When the authors studied specific fruit that probably formed part of the diet of the mastodons of Central Chile, they found that 40 percent of these species are now threatened. The Anthropocene Age has found many ways to make life hard for species, but 40 percent is disturbingly high. The authors note that in more tropical regions of the Americas, only 4-10 percent of large fruiting plants are similarly affected, which they attribute to the survival of tapirs and monkeys to act as seed dispersers.

“Where that ecological relationship between plants and animals has been entirely severed, the consequences remain visible even thousands of years later,” said Dr Andrea Loayza of Chile’s Instituto de Ecología y Biodiversidad.

A few plants have become so specialized that their seeds can only sprout after passing through an animal’s digestive system, making their demise swift after the disappearance of that species.

Most, however, can go on much longer, as the plants in this study have done. Fruit that drops on the ground sometimes finds fertile soil there, and some may roll a short way or be carried by a flood. However, if a disaster, natural or human-made, wipes the plant out in one location, it has little chance of recovering the territory from seeds shed elsewhere.

As a result, many central Chilean trees now survive only in isolated and inbred populations. Deliberate breeding programs may address this, but not easily.

“Paleontology isn’t just about telling old stories,” concluded Rivals. “It helps us recognize what we’ve lost—and what we still have a chance to save.”

The study is published in Nature Ecology and Evolution.

Source Link: South American Forests Are Still Missing Their Mastodons 10,000 Years Later