Brain matter is about the consistency of cream cheese. In fact, for humans, this gloop for a think-organ can even collapse under its own weight, so how can we ever hope to learn anything about the brains of long-extinct species? Well, a team of UK and US scientists recently demonstrated how, as they used computed tomography (CT) scanning to recreate the brains and associated soft tissues of two spinosaur specimens long after they had rotted away.

The findings follow two British fossils’ visit to the EvoPalaeo Lab and the μ-Vis X-ray Imaging Centre at the University of Southampton. Here, the specimens – Baryonyx from Surrey and Ceratosuchops from the Isle of Wight – were scanned by some of the most powerful CT scanners in the UK. They revealed a detailed look at the brain cases of these dinosaurs, and by working backwards the team could piece together a model of how their brains would’ve looked.

Spinosaurs are considered to have had quite an unusual ecology, as fishing dinosaurs that were aquatic to some degree (though this has been the subject of a lot of debate). As such, you might expect the brains to have evolved specialist features that lend themselves to such an extreme lifestyle, but this wasn’t what the researchers found.

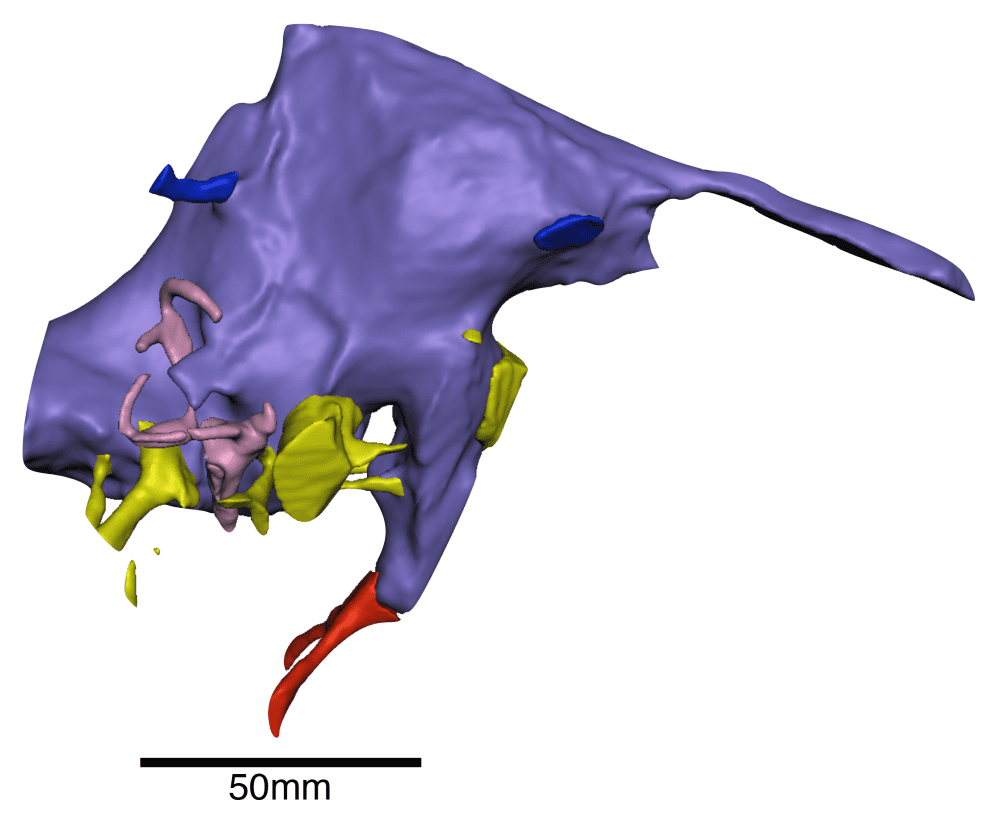

It’s possible the endocast may only give an overview of the gross brain shape, but it’s a significant leap forward in studying the soft tissues of ancient fossils. Image credit: Chris Barker

“Despite their unusual ecology, it seems the brains and senses of these early spinosaurs retained many aspects in common with other large-bodied theropods,” said University of Southampton PhD student Chris Barker, who led the study, in a statement. “There is no evidence that their semi-aquatic lifestyles are reflected in the way their brains are organised.”

The digitally reconstructed brains show evidence of a hearing system that was better suited to low frequency sounds, and slightly underdeveloped olfactory bulbs that are responsible for detecting smell. However, there was little to write home about in terms of adaptations specific to semi-aquatic life, but it’s possible that’s simply because growing the right shaped snout was enough for them to thrive in this habitat.

“Because the skulls of all spinosaurs are so specialised for fish-catching, it’s surprising to see such ‘non-specialised’ brains,” added contributing author Dr Darren Naish. “But the results are still significant. It’s exciting to get so much information on sensory abilities – on hearing, sense of smell, balance and so on – from British dinosaurs. Using cutting-edged technology, we basically obtained all the brain-related information we possibly could from these fossils.”

The findings are another example of how palaeontology can begin to close gaps in our knowledge of extinct species by recreating soft tissues from fossilized remains, as well as highlighting the value of British fossils in research. Such reconstructions can arguably only tell us part of the story, since not all brains are built the same, and the researchers say it’s possible that their approach was only able to identify the gross shape of the brain, but not the finer details that might lend themselves to life in the water.

Similar questions were raised earlier this year by a paper that suggested dinosaurs may have had similarly tightly-packed brains to modern birds, possibly giving them the cognitive capacity of a baboon. Others argued that this bracketing may have overlooked variation in brain anatomy, but perhaps that raptor really was a “clever girl” after all.

The spinosaur study was published in the Journal Of Anatomy.

Source Link: Spinosaur Skull Scans Reveal Their Brains Looked A Lot Like Other Dinosaurs'