When you think about Neanderthals, “master crafters” probably isn’t the term that comes to mind. But our ancestral cousins are nothing if not surprising – and, according to a new study out of the University of Wollongong, their ability to finely hone stone tools is just one of many things we’ve got wrong.

Go back 200,000 to 400,000 years, to when our Neanderthal ancestors were kicking about, and the latest in manufacturing technology was a method now known as Levallois. Basically, you take a piece of stone, bash it into a particular shape, and then get to knapping.

If you created that particular shape properly – it should look a little like a tortoise shell – then everything you knap off will be a nice, usable tool already. It’s an ingenious method, really, which is why even before now it was seen as a sign of some pretty impressive intelligence on the Neanderthals’ part.

“[T]he structured reduction pattern of the Levallois method is commonly attributed to more advanced cognitive abilities among hominin toolmakers,” the new paper explains, “involving foresight, planning and long-term memory to execute a ‘grammar-like’ action sequence.”

“Some researchers [have] argued that the consistent morphology of Levallois artefacts further signal the presence of linguistic and active teaching capacities among hominin toolmakers,” the researchers add.

But there’s always been a limit to how much credit we’ve given them. The Levallois technique may be smart, but it’s never been considered as entirely under those ancient crafters’ control. The shapes and sizes of the end products – those little arrow heads, knives, scrapers, and assorted other tools that made Middle Paleolithic life so much easier – were, ultimately, a consequence of the core, rather than the knapping.

In other words: screw up the preparation of that initial stone, and no amount of clever honing will fix what comes off it.

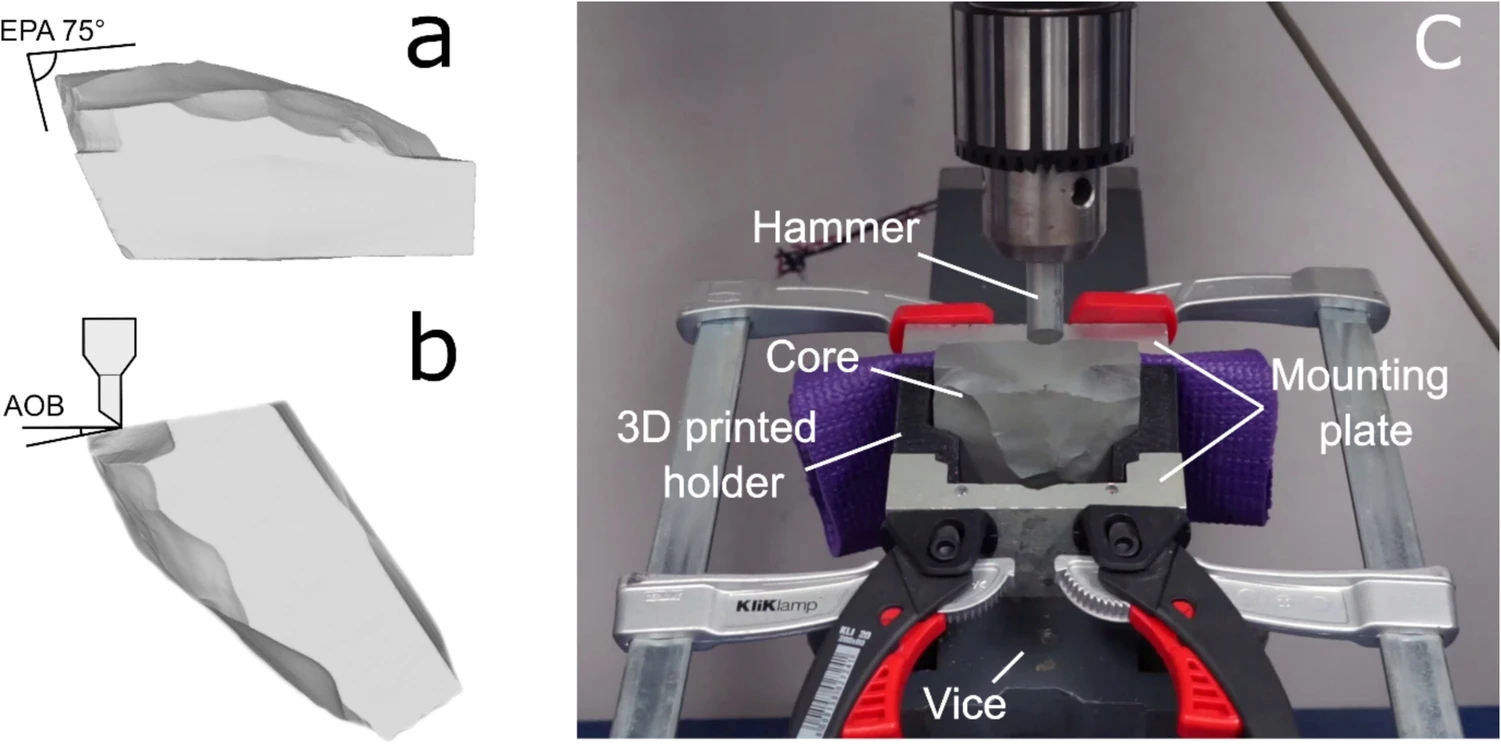

But the new study seems to contradict this idea. By 3D printing soda-lime glass cores – their design was based on a real flint-knapped Levallois core – the researchers were able to show by direct experimentation that, in fact, the angle at which the Levallois core is struck plays a much bigger part in determining the result than previously assumed.

The experimental setup.

“The results […] demonstrat[e] a clear effect of hammer AOB [angle of blow] on the morphology and fracture trajectory of Levallois flakes,” the team reports. “Our findings are consistent with those of previous experimental studies, showing that when core morphology and platform configuration are held constant, striking a Levallois core more perpendicularly, at a lower AOB, produces larger and heavier flakes compared to those struck at a more oblique AOB.”

Not only does this force us to rethink how Neanderthals approached toolmaking – and, by extension, how much more cognitive control our ancestors possessed than we previously thought – but it also clears up a few mysteries surrounding Levallois artefacts. “Previous studies have noted that preferential Levallois flakes tend to have more evenly distributed thickness and more obtuse edge angles than non-preferential flakes,” the team notes. “The effect of AOB observed here may play a role in explaining this variation.”

So, while more research is needed to investigate exactly how and why the angle of blow can affect tool production, one thing is for sure: our Neanderthal ancestors likely were, in every sense, sharper than we tend to assume.

The study is published in the journal Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences.

Source Link: Striking Results Show Neanderthal Crafters Were Sharper Than We Thought