Life is full of big decisions, and making a choice between seemingly endless options can be – well, paralyzingly hard. Should you buy this apartment, or that one? Share with this housemate, or someone else? Settle for Mr Pretty-Damn-Great, or hold out to see if Mr Perfect comes along?

It’s enough to make you despair – but fear not: science has the solution. Well, math does, at any rate.

Optimizing your options

Like a perhaps surprising number of mathematical factlets, this one found fame as a “for fun” puzzle set by Martin Gardner (the rest, of course, having been set by John Conway).

It was the year 1960, so the brainteaser was formulated as “the Secretary Problem” and ran like this: you need to hire a secretary; there are n applicants, to be interviewed, and accepted or rejected, sequentially in random order; you can rank them according to suitability with no ties; once rejected, an applicant cannot be recalled; finally, it’s all or nothing – you’re not going to be satisfied with the fourth- or second-best applicant here.

Other setups included the “fiancé problem” (same idea, but you’re looking for a fiancé instead of a secretary) and the “googol game” – in that version, you’re flipping slips of paper to reveal numbers until you decide you’ve probably found the largest of all.

However you play it, the question is the same: how can you maximize the probability of picking the best option available?

The answer is… surprisingly predictable, it turns out.

The 37 percent rule

Written out in words, this is a complex and unapproachable problem. In math, it’s pretty straightforward.

“This basic problem has a remarkably simple solution,” wrote mathematician and statistician Thomas S Ferguson in 1989. “First, one shows that attention can be restricted to the class of rules that for some integer r > 1 rejects the first r – 1 applicants, and then chooses the next applicant who is best in the relative ranking of the observed applicants.”

So, when faced with a stream of random choices and wanting to pick the best that’s thrown at you, the first thing you’ve got to do is… reject everyone. That is, up to a point – and once you reach that point, just accept the next applicant, suitor, or slip of paper, that beats everything you’ve seen so far.

The question now is simple: when do you reach that point?

Well, let’s say the stopping point is the mth applicant – everybody up to then gets rejected. Now, if the best applicant is the (m+1)th, congratulations, you’ll accept them and have the best possible hire.

But what if the best applicant is the (m+2)th? Well, then we have two ways this could go: either the (m+1)th was better than the first m, but not the best possible, in which case bad luck – you don’t get the best applicant, because you already chose their predecessor – or you rejected the (m+1)th and accept the (m+2)th.

Now, naturally, we want the second scenario, not the first – so here’s some good news: out of all arrangements of the first (m+1) applicants, there are only 1/(m+1) scenarios in which you’ll accept the (m+1)th rather than the (m+2)th. That means there are still m/(m+1) scenarios in which you hold out and get the best.

Okay, so what if the best applicant is sitting at (m+3)? Well, they get accepted only if neither applicant (m+1) nor applicant (m+2) beat everyone before them – and that happens in only 2/(m+2) of cases. Again, that means that you hold out for the best in m/(m+2) cases.

Perhaps you’re seeing a pattern already: in general, if the nth applicant is the best, they’ll be accepted m/(n – 1) times out of (n – 1).

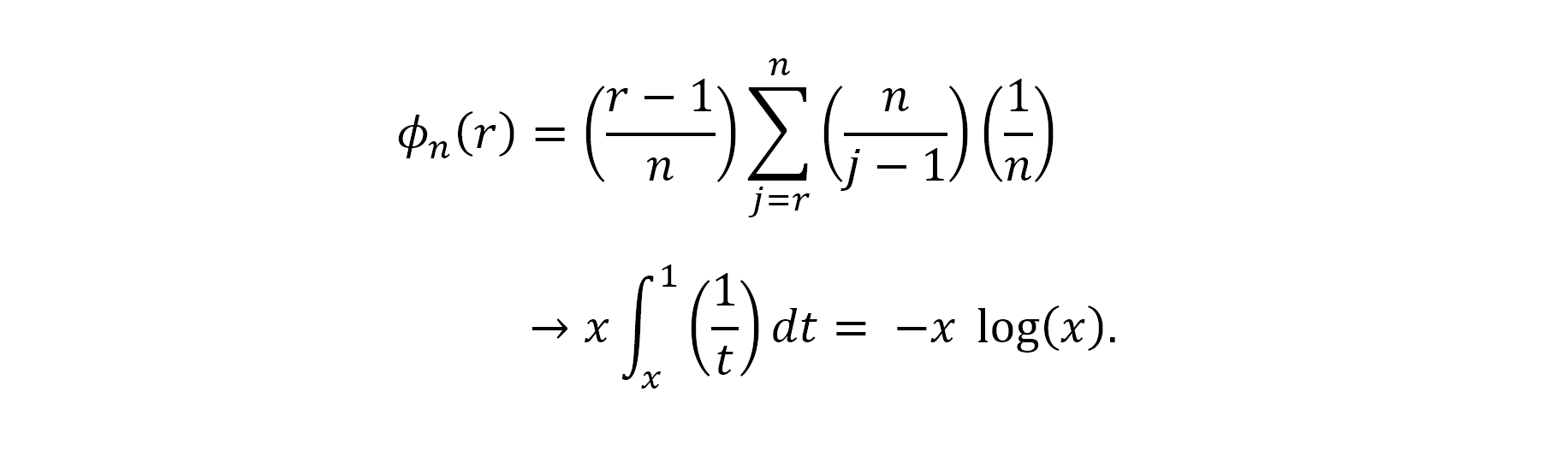

As we let n grow to infinity, this pattern becomes a limit. “The probability, ϕ(r), of selecting the best applicant is 1/n for r = 1,” Ferguson explains, “and, for r > 1 […] the sum becomes a Riemann approximation to an integral,

Image Credit: IFLScience, reproduced from Ferguson (1989)

Now the question is: how do we maximize that value? And the answer is actually pretty simple: you set x to be 1/e, which is roughly 0.368.

Because of the way that logarithms and exponents work, this means that ϕ(r) = 0.367879… too. In other words, “it is approximately optimal to wait until about 37% of the applicants have been interviewed and then to select the next relatively best one,” explained Ferguson. “The probability of success is also about 37%.”

That may not sound super impressive – it’s only just more than a one-in-three chance that you’ll find the best possible option, after all. But when you consider the alternative, it’s incredible: “If you chose not to follow this strategy and instead opted to settle down with a partner at random, you’d only have a 1/n chance of finding your true love, or just 5 percent if you are fated to date 20 people in your lifetime, for example,” wrote Hannah Fry, Professor of the Public Understanding of Mathematics at University of Cambridge, in her 2015 book The Mathematics of Love: Patterns, Proofs, and the Search for the Ultimate Equation.

“But by rejecting the first 37 percent of your lovers and following this strategy, you can dramatically change your fortunes, to a whopping 38.42 percent for a destiny with 20 potential lovers.”

Does it really work?

So: 37 percent. Doesn’t matter what you’re choosing; how many options you have; it all comes down to that all-important percentage. Sounds a little too good to be true, doesn’t it?

“I’m a mathematician and therefore biased, but this result literally blows my mind,” Fry wrote. “Have three months to find somewhere to live? Reject everything in the first month and then pick the next house that comes along that is your favorite so far. Hiring an assistant? Reject the first 37 percent of candidates and then give the job to the next one who you prefer above all others.”

So, if the logic is sound, and the math checks out – which it does – why does this result feel so wrong? Well, as Fry pointed out in a 2014 Ted Talk, there are some real-world wrenches that can get thrown in: “this method does come with some risks,” she said; “For instance, imagine if your perfect partner appeared during your first 37 percent. Now, unfortunately, you’d have to reject them.”

But “if you’re following the math,” she continued, “I’m afraid no one else comes along that’s better than anyone you’ve seen before, so you have to go on rejecting everyone, and die alone.”

Still, there is a way to avoid ending up as kitty-chow: lower your standards.

“The math assumes you’re only interested in finding the very best possible partner available to you,” Fry wrote. “But […] in reality, many of us would prefer a good partner to being alone if The One is unavailable.”

So, sure, you’ve about a 37 percent chance of finding The One by rejecting the first 37 percent who come along – but what if you’re okay with just finding One Of The Top 5 Percent, say? Well, in that case, your stopping point is lower: “if you reject partners who appear in the first 22 percent of your dating window and pick the next person that comes along who’s better than anyone you’ve met before […] you’ll settle with someone within the top 5 percent of your potential partners an impressive 57 percent of the time,” Fry explained.

Accept anybody from the top 15 percent of potential matches, and your chances climb even higher. Then, you need only reject the first 19 percent who come along – and you can expect a nearly four-in-five chance of success.

And let’s face it: when it comes to love, those aren’t bad odds. Beats astrology, at any rate.

Source Link: Struggling Over A Big Life Decision? Math Says You Should Use The "37 Percent Rule"