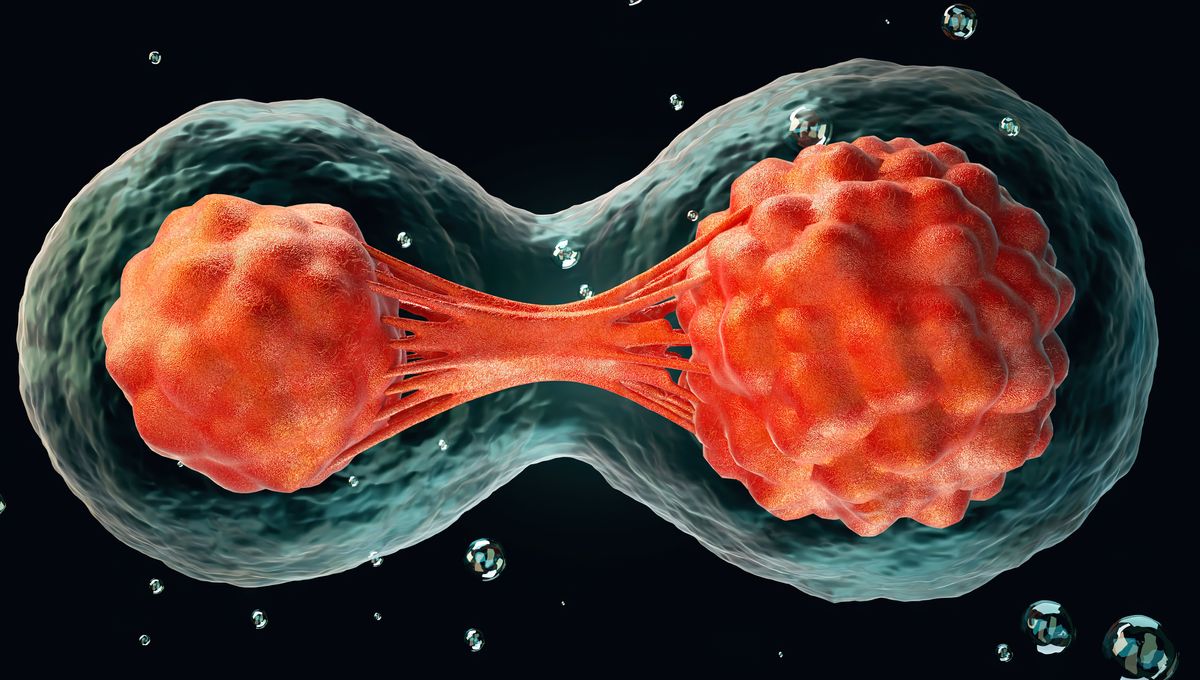

Synthetic human embryos – derived from stem cells without the need for eggs or sperm – have been created for the first time, scientists say. The structures represent the very earliest stages of human development, which could allow for vital studies into disorders like recurrent miscarriage and genetic diseases. But questions have been posed about the legal and ethical implications, as the pace of scientific discovery outstrips the legislation.

The breakthrough was reported by the Guardian newspaper following an announcement by Professor Magdalena Żernicka-Goetz, a developmental biologist at the University of Cambridge and Caltech, at the 2023 annual meeting of the International Society for Stem Cell Research. The findings have not yet been published in a peer-reviewed paper.

It’s understood that the synthetic structures model the very beginnings of human development. They do not yet contain a brain or heart, for example, but comprise the cells that would be needed to form a placenta, yolk sac, and embryo. Żernicka-Goetz told the conference that the structures have been grown to just beyond the equivalent of 14 days of natural gestation for a human embryo in the womb. It’s not clear whether it would be possible to allow them to mature any further.

This is not about creating lab-grown babies. Rather, it’s about lifting the lid on a period of human development that has thus far been closed off to scientists.

The law currently only allows for human embryos to be cultivated in a lab for a maximum of 14 days. After this point, there’s a window of time where developmental biology research is hampered, because scientists are only able to pick up the trail much later by studying pregnancy scans and donated embryos. It’s hoped that synthetic embryo technology could help bridge this gap.

Reacting to the news, other experts in the field of stem cell research highlighted the importance of bettering our understanding of embryonic development.

“The ability to recapitulate early events of human development using stem cells in a dish is a remarkable breakthrough in cellular and reproductive technologies,” said Dr Rodrigo Suarez of the University of Queensland in a statement. “The potential benefits are huge, and range from better understanding how the early tissues self-organise during stages that are otherwise unfeasible to study with current approaches, to elucidating the genetic and cellular requirements involved in early human development in health and disease.”

Stem cell-derived embryos have previously been developed in mice – also by Żernicka-Goetz’s group – and monkeys, and many had speculated that the human equivalent could not be far behind. However, passing this scientific milestone also brings with it a set of ethical and legal hurdles. One of the fundamental questions is: just how similar are these structures to natural embryos?

“If the whole intention is that these models are very much like normal embryos, then in a way they should be treated the same. Currently in legislation they’re not. People are worried about this,” explained Professor Robin Lovell-Badge, head of stem cell biology and developmental genetics at the Francis Crick Institute, to the Guardian.

“While it is not clear yet how these synthetic embryos might develop or be used in research, if it is determined they are not equivalent to human embryos, or it is possible to restrict their development such that they do not acquire certain characteristics associated with legal and ethical personhood, they could potentially be useful in research currently considered too risky to use human embryos,” said Dr Evie Kendal of Swinburne University of Technology in a statement.

Evidence from similar research in animals is mixed. When the monkey synthetic embryos were implanted into female monkey uteruses, most did not attach successfully, and the ones that did didn’t develop into viable fetuses. The mouse synthetic embryos developed far enough to start to form a beating heart and a brain, before succumbing to defects.

Lovell-Badge explained to the Guardian that it’s unclear whether there’s a biological reason why these structures can’t develop past a certain point, or whether these issues have been down to technical barriers that could theoretically be overcome.

In 2022, the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) licensed a technology developed at Monash University called iBlastoids. These are models of very early human embryos made from reprogrammed adult skin cells, and are not able to develop into a mature fetus. Controversially, the NHMRC ruled that these structures came under the same legal protections as normal human embryos, making them subject to the 14-day rule.

That’s just one example, but it highlights the complexities of this issue. What most experts seem to agree on is that there is a pressing need for regulators around the world to start to match the pace of these new developments, so that we can more clearly define exactly what these synthetic embryos are – in a legal sense – and how they may be used.

Source Link: Synthetic Human Embryos Have Been Made In A Lab For First Time, Scientists Say