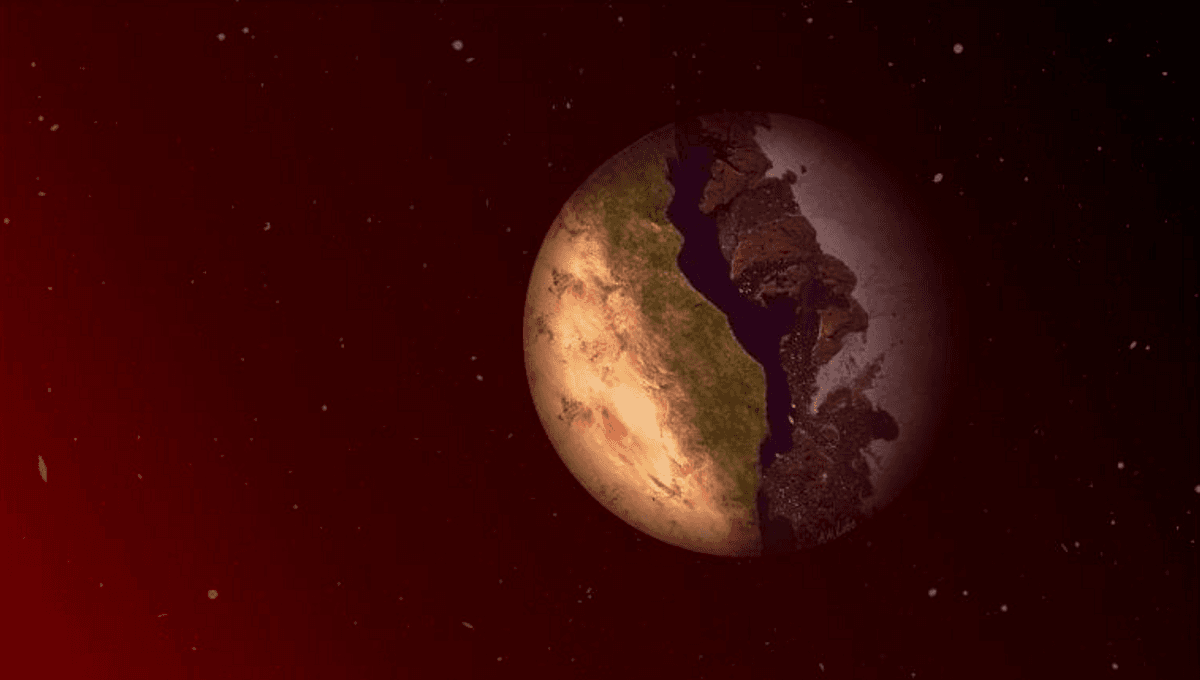

The “terminator zone” doesn’t sound like a good place to seek extraterrestrial life, but it might be our best chance, new research suggests. These zones are marked by perpetual twilight and are a feature of most of the known planets with prospects for hosting life while being close enough to study. Consequently, the question of their habitability is one of the most significant in determining our prospects for finding life beyond the Solar System.

Most moons, like our own, are tidally locked to their planet, with one side always facing the planet. Modeling suggests the same is true for most planets in close orbits. Locked planets of a star like the Sun are likely to be far too hot to support life – even Mercury isn’t tidally locked yet – but it’s a different matter for red dwarfs.

Red dwarfs are by far the most common type of star in the galaxy and if a planet is close enough to them to not be an ice-world, it’s probably tidally locked. At suitable distances their daylight side is likely to be too hot, and probably blasted by flares. Their night side will have no energy source for life. Any prospects therefore depend on a narrow region known as the terminator zone, so it’s just as well a paper in The Astrophysical Journal concludes these can be suitable.

“You want a planet that’s in the sweet spot of just the right temperature for having liquid water,” said Dr Ana Lobo of the University of California Irvine in a statement.

Proxima Centauri b, the (equal) closest planet to Earth outside the Solar System, is an example of a tidally locked world where the terminator zone carries any hope for life.

Although many terminator zones’ average temperatures and radiation exposure might suit liquid water, and even photosynthesis, that doesn’t necessarily mean life is possible there. For one thing, such zones would be subject to strong ceaseless winds caused by the temperature gap. Evaporation on the dayside could create atmospheres loaded with water vapor and a runaway greenhouse effect. A baking desert and field of ice would leave little room for oceans at moderate temperatures.

This has caused uncertainty as to whether temperatures would be stable enough under such conditions to maintain liquid water, so Lobo and co-authors conducted detailed modelling. They conclude that, given the right initial conditions, lakes and ponds could survive.

In contradiction to what we usually look for in planets, the prospects are better if water is not too abundant. “Ana has shown if there’s a lot of land on the planet, the scenario we call ‘terminator habitability’ can exist a lot more easily,” said co-author Dr Aomawa Shields. “These new and exotic habitability states our team is uncovering are no longer the stuff of science fiction– Ana has done the work to show that such states can be climatically stable.”

If life can only survive on a small portion of a planet’s surface it may not change the atmosphere to the extent that has occurred on Earth, which could make it much harder for us to detect life’s presence. Reduced cloud-cover may offset this, however.

Proxima b is unlikely to be neglected given its unique location and Earth-like size. However, work like Lobo’s could determine whether other nearby tidally locked planets or more distant planets around larger stars are the focus of attention for telescopes capable of detecting atmospheric composition.

Terminator zones are not named after killer robots, but from the line between day and night on the Moon being called the terminator. The terminology has been extended to other planets.

The study is published in The Astrophysical Journal.

Source Link: Terminator Zones Could Be Sanctuaries For Life Around Faint Stars