Space, famously, is the final frontier. That makes just about everything we do there unprecedented – and sometimes, they’re un-succeeded, too.

One such event – never before tried; never since repeated – was the flight of Soyuz T-15. With a crew of just two cosmonauts, featuring a Soviet space station on its last legs, and under circumstances no spacefarer would hope for, this mission nevertheless achieved something remarkable: it was, and remains, the only time anybody has visited two space stations in one trip.

So what prompted this historic journey? And why haven’t we managed to do it again?

In space, nobody can hear you scream

It was 1986, and the Cold War was still as icy as ever. The Iron Curtain was drawn; the US was busy illegally selling arms to Iran in order to fund right-wing militias in Central America; McDonald’s was losing money hand over fist due to Olympics boycotts – you know, all the standard 20th-century nonsense.

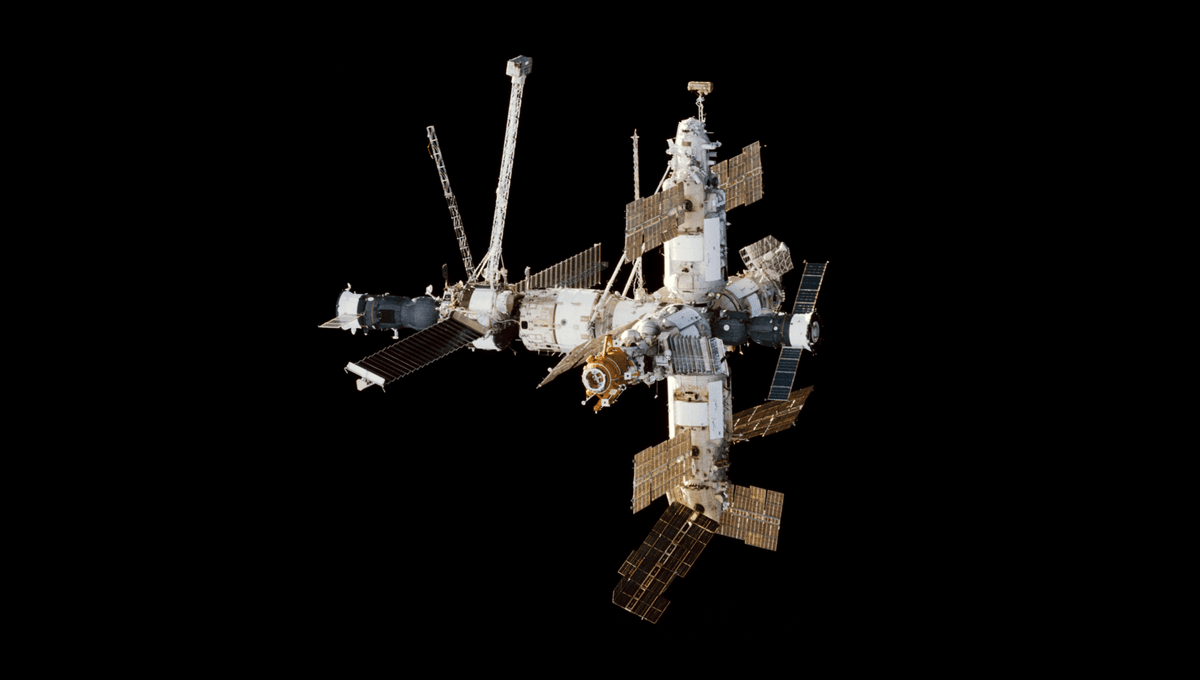

And yet, despite all that, the initial reason for such an unusual flight was completely practical. The old Salyut-7 space station, orbiting Earth since April 1982 and running on equipment largely from the mid-1970s, was reaching the end of its usefulness. Long beset by the kind of luck that wouldn’t seem out of place in a Greek tragedy, the stations’ operations were finally being wound down; its successor, Mir, had been launched a few months previously, but no cosmonauts had yet been on board.

It should have been a clean changeover. Unfortunately, fate – and the ambition of one Commander Vladimir Vladimirovich Vasyutin – had other plans.

“It all began when we noticed a slight uneasiness in Volodya Vasyutin’s behaviour,” wrote Viktor Savinykh, the flight engineer on Salyut-7, in his onboard diary of 1985. “There was a loss of sleep and appetite. We thought it was all to do with his mood – it happens to us all. We tried to buck him up by cracking jokes and giving bits of advice. Then the pain appeared.”

Eventually, it would be reported that Vasyutin had come down with some kind of urological infection – some sources say a prostate infection, but no official diagnosis was ever made public. Despite weeks of suffering – and, Savinykh griped, quite a lot of complaining about it – and various attempts to treat him in-orbit, eventually the whole mission had to be called off.

What had been slated to last six months had, therefore, only lasted two – which left quite a lot of work unfinished. Several spacewalks had to be canceled; Savinykh’s ongoing attempt to break the space endurance record was brought to a sudden end. “Volodya wanted to see it through,” Savinykh recalled, “but things became increasingly difficult for him […] The health of a comrade should never be put at risk.”

Perhaps most important, though, considering the station’s imminent decommissioning, were the numerous military experiments that were halted, their equipment left on board as the crew hastened back to Earth a mere one-third of the way through their schedule. Before Salyut-7 could be replaced with Mir, all that work would need to be finished, and the equipment collected and moved over.

Unfortunately, that wasn’t going to be easy.

Planning the journey

In theory, this shouldn’t have been a complicated job. Send a crew up to Salyut-7, have them finish the work, and bring them back on a schedule resembling the original team’s.

Except. Here’s the problem with that: the USSR was sort of… between cosmonautical setups at that particular point. They had one remaining transport spacecraft from the old Soyuz T line, and that was already slated to send the first team up to Mir in March; the next generation of spacecraft, the Soyuz TM, would not be certified to carry cosmonauts for another nine months or so.

Stuck for a spare vehicle, and working to a political timeline, the Soviet cosmonautical authorities did the only thing that made sense: they went for a twofer. A pair of cosmonauts, Leonid Denisovich Kizim and Vladimir Alekseyevich Solovyov, would take the last Soyuz T spacecraft – Soyuz T-15 – up to Mir, and do something never tried before: they’d commute from one space station to another, and back again, all within the same mission.

It wouldn’t be easy, even by space expedition standards. Mir’s planned position in space needed to be adjusted to be in line with Salyut-7’s orbit; still, extending the length to be traveled by the shuttle meant that a much slower, more conservative journey would need to be taken to get there. To prepare for the double mission, Kizim and Solovyov would need extra training; to make matters even worse, just days before they were set to blast off, Salyut-7 once again started glitching out, meaning the mission would have to include a quick mechanical tune-up on top of everything else.

Nevertheless, they held firm. On March 15, 1986, Kizim and Solovyov stepped off the Soyuz T-15, and became the first people to enter Mir. The new space station had seemed “like a giant white-wing seagull soaring above the Earth” as they approached, Kizim reported – but inside, it was a blank canvas. It would take a little over seven weeks of work for the pair to activate Mir, setting it up for the future cosmonauts and, later, astronauts that would spend time there.

And then, instead of enjoying the fruits of their labor, they got back onto their Soyuz shuttle and left for Salyut-7.

Packing up

“It is like I never left,” joked Kizim as the pair entered the older space station – like Solovyev, he had already logged hundreds of hours on Salyut-7 working on precisely the kind of military and scientific experiments that had been so abruptly called off months earlier.

But while completing that work had been their earliest priority, it was no longer their first one. Instead, they now had to wade through the mess of electronics to find whatever had gone wrong with Salyut-7’s mainframe, and hopefully fix it so the station could once again propel itself through space. This task, though, would prove to be a non-starter: the problem couldn’t be found, and the two cosmonauts instead had to jimmy a workaround by inserting a cable that could bypass the problem.

Such a MacGyvered solution may not have filled your average person with confidence – but for Kizim and Solovyev, it would have to do. They had work to do: spacewalks to complete; experiments to wrap up and dismantle; the potential for an agonizing, drawn-out death in the cold expanse of space to grapple with.

No, we’re not kidding. “Engineers were concerned about possible new short-circuits and faulty commands, especially [on] spacewalks,” explained Russian space expert Anatoly Zak in a 2016 article for Smithsonian Magazine. “What if some errant command locked the cosmonauts outside the station?”

Nevertheless, “after some debate and testing, flight controllers allowed the crew to proceed with two spacewalks,” he wrote. “By the time they finished, Kizim and Soloviev had logged more than 30 hours outside, without any serious problems.”

With the work done, the pair loaded up the Soyuz with everything it could carry – “400 kilograms [882 pounds] of cargo, including a guitar,” Zak noted – and ferried themselves back to Mir. Having been the first on board the new space station, they were now also the last to leave the old one.

Ever after

So, what became of the characters in this story? Well, for Kizim and Solovyov, the story past their historic journey was fairly standard: they spent four months in space, returning to Earth on July 16. They had originally been slated to stay about a month longer – but all their objectives were complete, and nothing new was scheduled to happen on Mir until the next year. It was eventually decided to call the mission off early, and allow the overworked cosmonauts some well-deserved shore leave.

Mir, meanwhile, was extremely successful. It stayed in orbit for 15 years, only being deorbited in 2001. It survived the fall of the USSR, and hosted international cooperation from around the world – including with their old enemies, the US.

Salyut-7, meanwhile, had a somewhat less grand end. Rather than deorbit it, the USSR space agencies decided to kind of extra-orbit it, pushing it into a higher orbit. The plan was for it to stay there for about a decade – the higher altitude was assumed to mean it would take a long time to decay, and so a Buran shuttle could be sent to retrieve it at a later date – but in a turn of fortune that was by this point normal for the beleaguered Salyut-7, it was instead battered by unexpectedly high solar activity only a few years in, and it crash-landed in Argentina in February 1991.

For the last half-decade or more, Salyut-7 had seemed almost cursed with chronic bad luck. It had nearly killed its occupants on multiple occasions; it had seen cosmonauts grow sick and missions called off; now, it was crashing to Earth years before it was forecast to be decommissioned. But there’s one thing it will always be able to boast: for one glorious month in 1986, it was one-half of a mission that has never since been achieved. And that’s… well, it’s something.

Source Link: The 1986 Soviet Space Mission That's Never Been Repeated: Mir To Salyut And Back Again