In math, more than any other discipline, reputation is irrelevant. It’s not that it counts for nothing – but with vanishingly few exceptions, if you don’t have a valid proof, your proposition isn’t going to be accepted just on the strength of your name alone.

Nobody believed in that tenet more than Richard Dedekind, a prolific 19th-century mathematician who famously stated that “what is provable should not be believed in science without proof.” It’s a mark of just how highly respected he was, then, that he managed to get generations of mathematicians looking for a sequence of numbers that seemed all but impossible to pin down – and of which he himself only had five slightly shaky terms – just because he thought they were interesting.

“Given a finite system of natural numbers, and if one calculates all the greatest common divisors of two or more of these numbers, the latter are thereby factored into factors in manifold ways,” he began, in an 1897 treatise that would go relatively unnoticed at the time. “Although these factors are generally known not to be prime numbers, they nevertheless serve their purpose well in some investigations, and it is therefore worthwhile to present the laws arising in this process in a coherent manner […] I hope that in this respect my work will be welcome to some mathematicians.”

Some 44 pages later, he had the beginnings of what are now known as the Dedekind numbers: in his formulation, 0, 1, 4, 18, and, “if I have not erred,” he wrote, 166. The terms “seem[ed] to grow very rapidly,” he noted, but “I have not yet attempted to find a general expression for [them].”

Today – more than 125 years later – we still don’t know how to find the Dedekind numbers in general. In fact, we only very recently managed to find the ninth one in the sequence. So why are they so difficult to find?

What are the Dedekind numbers?

There are three ways you can think of Dedekind numbers – though, fair warning, none of them are exactly easy to understand.

The first is probably simplest, though, if only by virtue of being the most visual. “Basically, you can think of [it] as a game with an n-dimensional cube,” explained Lennart Van Hirtum, a researcher at the Paderborn Center for Parallel Computing at Paderborn University, back in 2023. “You balance the cube on one corner and then color each of the remaining corners either white or red. There is only one rule: you must never place a white corner above a red one.”

“This creates a kind of vertical red-white intersection,” he said. “The object of the game is to count how many different cuts there are. Their number is what is defined as the Dedekind number.”

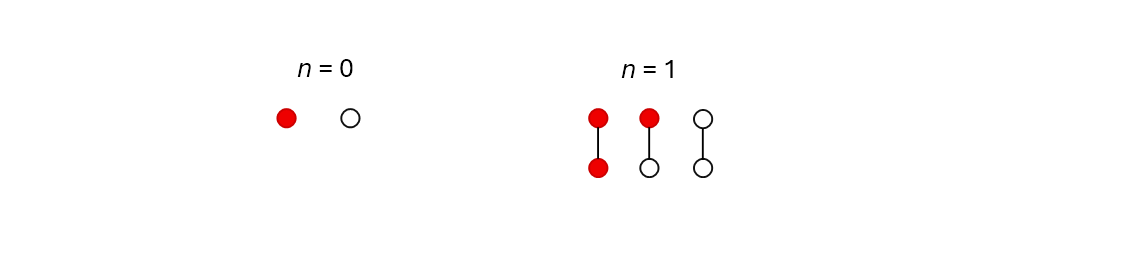

The easiest place to start here is in zero dimensions – that is, the case where n = 0. That’s going to be just a single point: it can be either red or white, so the zeroth Dedekind number is 2. In one dimension, we have just a line with two “corners”, and three ways to color them so that no white corner is ever higher than a red one:

The possibilities for n=0 and n=1.

Image credit: © IFLScience

For two dimensions, there are six possibilities:

The six possibilities in dimension 2.

Image credit: © IFLScience

And in three, there are 20. Past that, it gets harder to imagine – our brains aren’t wired for imagining dimensions higher than three. But Dedekind managed one more level: for n = 4, the Dedekind number is 168. And if you’re wondering why all of our answers are two larger than his, don’t worry – it’s not a typo, it’s just that modern mathematicians include a couple of answers that Dedekind himself considered trivial.

Alternatively, you can think of them in terms of subsets and lattices. Imagine a set with n elements – the most obvious being the set of the first n natural numbers {1, 2, 3, …, n}. The power set of this set – the set of all possible subsets of that set – will then have 2n elements, and all of those elements can be arranged into a mathematical structure known as a subset lattice.

The subset lattice for the set {1, 2, 3}.

Image credit: © IFLScience

The Dedekind numbers are defined on these lattices as the number of anti-chains that can be found – in other words, the number of ways you can specifically not connect up all the vertices together. For example, in n = 3, {{1}, {2, 3}} would be an anti-chain; {Ø, {1}, {1, 2, 3}} would not.

Finally, we have the way Dedekind himself defined the numbers: in terms of monotone Boolean functions. This is probably easiest to understand if you’re literally a computer, as it’s all kind of binary. First, we take n variables that are either 1 or 0 (or equivalently, either “true” or “false”), and we apply a function that produces as an output from these n variables another 1 or 0 – these are all so-called “Boolean” variables.

Now, that function is called “monotone” if for every combination of inputs, switching one of them from 0 to 1 (or from false to true) can only cause the output to change from 0 to 1 (or false to true) – but strictly not in the other direction. The number of these monotone functions that it’s possible to find for n Boolean variables is the nth Dedekind number.

These methods are all equivalent – it really just depends on which you find easiest to understand. But whichever you prefer, Dedekind certainly had one thing correct. “The numbers quickly become gigantic,” Van Hirtum said. “The 8th Dedekind number already has 23 digits.”

The search for Dedekind numbers

With no general way to locate the Dedekind numbers, and their growth being so incredibly fast, the hunt for the 5th, 6th, and higher-order numbers quickly stalled. It took more than 40 years before anybody found number six: 7,581, the fifth Dedekind number.

Number seven – the sixth Dedekind number – came a comparative blink later, in 1946, and it was a doozy. The sequence had jumped from four digits to seven: from 7,581 to 7,828,354. The seventh Dedekind number was found in 1965 – it’s 2,414,682,040,998 – and the eighth is firmly millennial, arriving in 1991. At 56,130,437,228,687,557,907,788, it’s roughly the same magnitude as the diameter of our Solar System measured in microns, and its discovery took 200 hours of computation on one of the most powerful supercomputers of the time.

“Historically, a new Dedekind number has been discovered every 20 to 30 years,” Bartłomiej Pawelski, a computer scientist at the University of Gdansk in Poland, told Scientific American in 2023. “[It’s] “a computational challenge.”

The ninth Dedekind number, then – still undiscovered by 2023, some 32 years after its predecessor was found – was overdue. “The calculation of D(9) was an open challenge,” Van Hirtum said, “and it was questionable whether it would ever be possible to calculate this number at all.”

And then, two teams found it at once.

An incredible coincidence

Moore’s Law states – more or less – that computing technology doubles in power roughly every two years. Over three decades, then, hopefully, things should have advanced far enough to find D(9).

“It […] seemed conceivable,” Van Hirtum said. “It should be possible by now to calculate the ninth number on a large supercomputer.”

But at first, at least, the math wasn’t encouraging. With modern computers and more efficient algorithms, Van Hirtum’s team was able to rediscover D(8) in just eight minutes on a normal laptop – but “what takes eight minutes for D(8) becomes hundreds of thousands of years for D(9),” he explained. “Even if you used a large supercomputer exclusively for this task, it would still take many years to complete the calculation.”

Some kind of simplification was needed. “In our case, by exploiting symmetries in the formula, we were able to reduce the number of terms to ‘only’ 5.5×1018 – an enormous amount,” Van Hirtum said. “By comparison, the number of grains of sand on Earth is about 7.5×1018.”

As luck would have it, though, he happened to know one of the few places kitted out for such a mammoth undertaking. It was a “moonshot project,” said Christian Plessl, head of the Paderborn Center for Parallel Computing, but Noctua 2, one of the supercomputers at the center, “is one of the few supercomputers worldwide with which the experiment is feasible at all.”

After three years of theoretical work, the time had come to set the computer to work. Their method was precarious – “we calculated there was a 25 to 30 percent chance” that cosmic rays might have interfered with the specialized circuitry that ran the supercomputer – but all they could do was wait.

Unbeknownst to them, they weren’t the only ones waiting.

Christian Jäkel was an established mathematician at the Dresden University of Technology, but he’d been working on the problem of D(9) since his PhD years, more than half a decade earlier. “Actually, the Dedekind problem was not the content of his dissertation, but when he stumbled upon the problem, he was fascinated by it,” Stefan Schmidt, a professor at Dresden’s Faculty of Mathematics and Jäkel’s doctoral supervisor, said in 2023. “He was obsessed with the idea of determining the ninth Dedekind number.”

His own method for chasing the number was very different from the Paderborn team’s: it was based on matrix multiplication, using techniques that are “very, very established,” he told Scientific American. It was so comparatively simple, in fact, that he didn’t even need a supercomputer to run it – even if he did need a full month of calculation time once he set it running.

The race was on – and Jäkel, it turned out, would cross the finish line first. In March 2023, he posted his result – the stonking, 42-digit behemoth of 286,386,577,668,298,411,128,469,151,667,598,498,812,366.

He had not checked his work. “I did everything I could in my power” to avoid mistakes, he told Scientific American. “I observed this calculation very carefully.” But short of confirming the result with another method, there was no way to be sure.

“I had this number, and I thought it [would take] ten years or so to recompute it,” he said. “Three days later, I had the confirmation.”

While the Paderborn team had technically found their result first, they had waited to publish – fearing, as Jäkel had, that a mistake may have crept in somewhere. But with both papers posted – and both teams having arrived at the same number – the two solutions basically confirmed each other. “To have it verified after such a short time was overwhelming,” Jäkel said.

The hunt for D(10)?

The challenge, after 32 years, had finally been resolved – so when should we expect to see D(10)?

Well, the jury’s out on whether we ever will. Our computers may be better than ever, but “[the] jump in complexity remains absolutely astronomical,” Van Hirtum told New Scientist in 2023. To find it would require the power output of the entire Sun, he pointed out; the answer alone should be roughly the same as the number of atoms in the visible universe. It is, as they say, a Big Ask.

“I think it’s pretty safe to say the 10th one will not be calculated soon,” Van Hirtum told Scientific American. “And by soon, I mean the next few hundred years.”

Jäkel is similarly stoic. “From D(7) to D(8), and from D(8) to D(9), it took about 30 years in each case,” he pointed out. “I see no reason why it should go faster from D(9) to D(10.”

“I will of course keep a close eye on developments around the Dedekind numbers,” he added. “There are ideas that I would like to try out, but I’m not hoping to be able to calculate D(10).”

Source Link: The 9th Dedekind Number: Why It Took 32 Years To Find, And Why We May Never See A 10th