The Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the most powerful particle accelerator on the planet, can provide a tremendous amount of energy to particles and ions, making them go up to 99.9999991 percent the speed of light. This energy is incredible but tiny compared to occasional high-energy cosmic rays, which make the LHC protons look like snails. We do not know the source of these celestial events, but a new paper has a bold proposal. The answer might be hiding in the aftermath of supernovae.

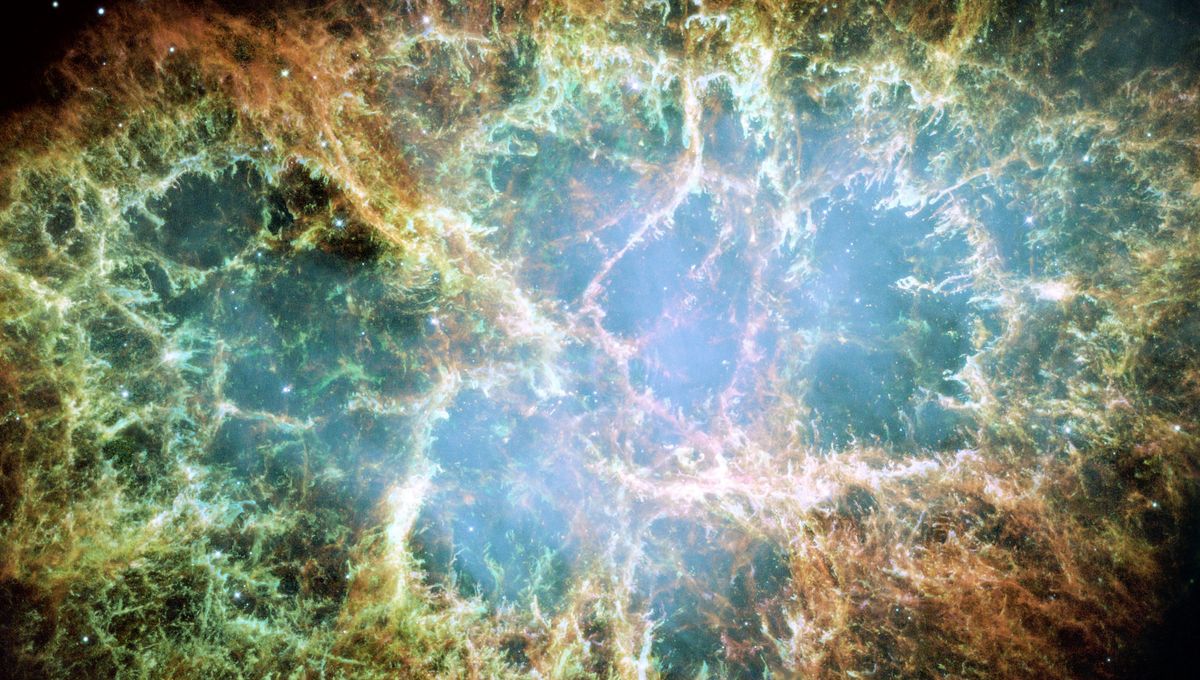

We recently saw a supernova remnant that was a perfect sphere. This was possibly due to the lack of dense interstellar material around it, but it is the exception rather than the rule. Most of the time, the material ejected at high speed from supernovae slams against the interstellar medium; that is where the magic might happen.

Supernovae are extremely powerful events. Some generate powerful gamma-ray bursts, which can outshine the universe in gamma rays for a brief time. The supernovae can be so powerful that they leave behind incredibly dense objects like neutron stars and black holes, or nothing at all in the case of the most massive ones. It has long been considered that these events could also accelerate cosmic rays to really high energies, but observations of supernovae remnants have not shown evidence of these extreme cosmic rays.

But what if the source was not just any supernova or supernova remnant, but specific ones? Researchers have created a simulation that suggests that it is possible for supernovae to be particle accelerators that launch cosmic rays to petaelectron volts of energy. That is at least 100 times more energy than the LHC.

You need to start with a star shedding material ahead of the explosion, something common in several types of supernova. Evolved stars are very large, and the gravitational pull on their outer layers is not very strong. However, the material can’t spread too far, because staying dense is key to accelerator processes.

Once the star explodes, stellar material will be flung towards this dense shell of stuff. The collision creates shockwaves. Magnetic fields ramp up to extremely high energies, accelerating particles. Particles also interact with each other, adding to their energy, until they escape the supernova remnant with unparalleled speed.

The material in the supernova remnant will continue to expand, and the whole setup has less energy, so the cosmic rays are less energetic. To catch the cosmic rays at those energies and match them from a specific supernova, you need one that happened recently and close by. But we have not had one of those in a long while. So the origin of extreme events like the highest-energy cosmic neutrino remains a mystery.

A paper describing a simulation is accepted for publication in Astronomy & Astrophysics and is available on arXiv.

[H/T: Live Science]

Source Link: The Aftermath Of Supernovae Might Hide The Universe's Most Powerful Particle Accelerators