If you could ask Thomas Jefferson where the roots of American democracy lay, he’d likely point to the English Magna Carta, or the one-man, one-vote (or to be precise, one-man-over-18-with-two-Athenian-parents-who-isn’t-a-slave-or-a-freed-slave-or-foreign-or-descended-from-a-foreigner-or-in-debt-or-a-criminal-or-descended-from-either, one-vote) system of ancient Athens. Which is odd, really – because why would you “bring democracy” all the way from Europe when it was already in America to begin with?

“These kinds of democratic institutions were very long lived and existed – perhaps for millennia – before European arrival,” said Victor Thompson, Distinguished Research Professor and director of the Laboratory of Archaeology at the University of Georgia, in a statement. He’s lead author on a paper, published in the journal American Antiquity, which argues that democratic-style collective governance could be found in the Americas at least 1,000 years before European colonization came to the continent.

It’s “a really different perspective on Native governance in this region than most archaeologists have,” Thompson said. While mainstream history books will sometimes point to the Iroquois Confederacy as one example of an early American democracy, this only places the social system as existing a couple of decades before European contact.

By contrast, the researchers’ analysis of existing artifacts from the Cold Springs site in central Georgia, where Ancestral Muskogean communities built large circular public buildings called Cukofv Rakko, indicates that collective governance was around as early as 500 CE – a millennium earlier than is generally assumed.

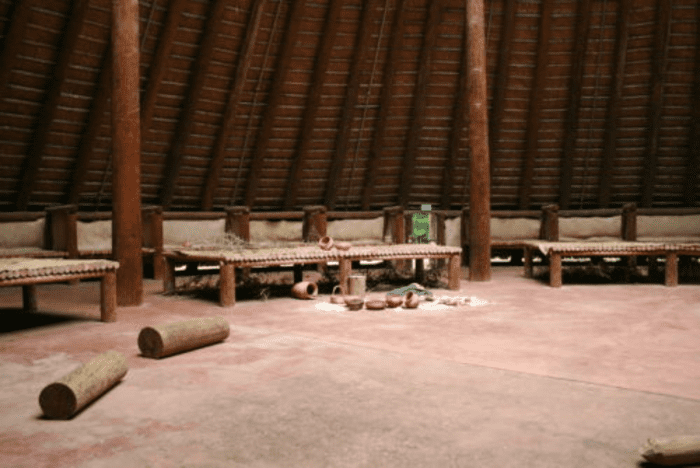

Also referred to as rotundas or townhouses depending on the region, council houses often had highly structured seating arrangements denoting rank and status, as well as painted histories of the community on their walls. Image: UGA Library of Archeology

“That’s the beauty of museum collections,” said Thompson. “They’ve just been sitting there, and they can tell you so much. All it really takes is new ideas, new methods, to be able to go back and look at these collections again.”

So the researchers performed new radiocarbon dating of artifacts that had previously been sitting in the Laboratory of Archaeology’s collections for nearly 50 years – Cold Springs was excavated in the early 1970s, before the completion of a dam in the Oconee river that would ultimately submerge the site under Lake Oconee. The sheer number of new results makes Cold Springs now one of the best-dated early mound sites in the Southeast US – but this hard science wasn’t the end of the study.

“We were meeting on Zoom and looking at pictures of post holes – tons of pictures of post holes,” said RaeLynn Butler, manager of the Historic and Cultural Preservation Department for the Muscogee Nation, in Oklahoma. “Our major contributions were to digest the information and provide the traditional knowledge and perspectives as tribal people that helped bring to this research some much-needed context of our social organization and traditional forms of government.”

It’s a perspective that has historically often been ignored in archaeology. The common image of Indigenous American cultures being primarily chiefdoms, led by unquestioned autocrats who held significant power over their tribe – that didn’t come from the Indigenous people themselves, but from Spanish explorers and colonizers. The idea “is a nuisance, and it’s a grand narrative that’s been very hard to overcome,” said Turner Hunt, preservation officer for Muscogee (Creek) Nation and a co-author of the paper.

“We still have a National Council in our council house, which meets within it and passes national laws – it’s been this way for hundreds of generations,” he said.

Which rather cuts to the heart of the paper. Cold Springs, both Hunt and Butler highlighted, isn’t Stonehenge, or the Pyramids of Giza – it’s an archaeological site stretching back more than a millennium, sure, but “there is a living, active culture that is directly connected to it,” Hunt pointed out.

“We believe our governments, our democratic institutions, have been practicing this way of life for thousands of years,” he said. “We are connected to these people through the way we still conduct ourselves today.”

Source Link: The Birthplace Of American Democracy Wasn't Where – Or When – You Think