Where the Earth’s core meets the mantle, there are two giant regions that have baffled geologists for fifty years. A new piece of the puzzle has now emerged with the discovery that they have different compositions from each other, challenging models that assumed they had similar origins.

ADVERTISEMENT

Most of what we know about the inner structure of the Earth comes from seismic waves produced by earthquakes, and the way their speed varies in different parts of the planet and sometimes bounces off the boundaries. One relatively early discovery was that the lower mantle is not consistent where it meets the core. Instead, there are two giant areas where the seismic waves slow down, known as Large-Low-Velocity-Provinces (LLVPs), or sometimes Large Low Shear Velocity Provinces.

For decades, we knew little about the LLVPs other than their locations – one under Africa, Spain, and parts of the Atlantic; and the other beneath the Pacific Ocean – and their approximate extent. However, progress has sped up, and geologists now think they are composed of relatively dense oceanic crust which broke off the rest of its plate and was forced through the mantle.

We’ve also learned they might be up to 900 kilometers (559 miles) high – which, combined with covering more than a quarter of the core, means these are major features of the planet to not understand. Earlier this year, some of the previously mysterious observations were attributed to large grain sizes within the LLVPs, a sign they are very old.

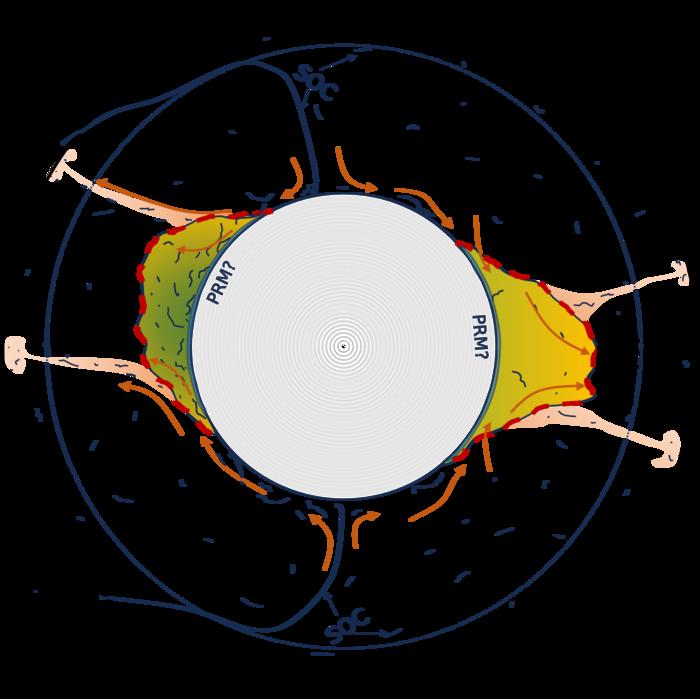

All this time, however, they were thought to be similar in composition and origin. According to the authors of a new study, the African LLVP is considerably older and is made up of better-mixed material than the Pacific LLVP, which contains a lot of young oceanic crust that has been forced deep into the Earth.

Geologists and astronomers have different meanings for words like “young” from the rest of us, and in this case, they mean a significant contribution within the last 300 million years.

The African LLVP also extends higher off the surface of the core, compensating for its lower density, so the overall effect looks relatively similar to our instruments.

Comparison of the two LLVPs. Young oceanic crust is feeding the Pacific LLVP (green), while the African one is older, higher, and better mixed. Each could be contributing to potentially volcanogenic mantle plumes

Image Credit: Dr Paula Koelemeijer

We can’t get samples from either of them, so these conclusions are based on models of the way convection drives circulation within the mantle. The team thinks the fact the two LLVPs are on almost opposite sides of the Earth is not a coincidence, instead representing a natural consequence of gravitational settling and the way the subducted crust is stirred through the mantle. That hasn’t stopped them migrating somewhat, for example with the African LLVP moving south over the last few hundred million years.

“As numerical simulations are not perfect, we have run multiple models for a range of parameters. Each time, we find the Pacific LLVP to be enriched in subducted oceanic crust, implying that Earth’s recent subduction history is driving this difference,” lead author of the study, Dr James Panton of Cardiff University, said in a statement.

The team thinks that subduction zones along the Ring of Fire, which roughly follows the borders of the Pacific Ocean, are replenishing the Pacific LLVP with oceanic crust forced beneath overriding continents. The African plate is moving much more slowly, and therefore feeding less crust to the LLVP below. What does get forced down mixes more with the mantle during its long descent, at least partially explaining the lower density.

All this contradicts previous theories that LLVPs are a legacy of the collision that formed the Moon.

ADVERTISEMENT

With only two LLVPs, and plenty of research into them, you might expect these differences would have been noticed previously. However, the team say the variation was obscured by the fact they share the same temperature, which is the most important influence on seismic waves’ speed.

“The fact that these two LLVPs differ in composition, but not in temperature is key to the story and explains why they appear to be the same seismically,” said co-author Dr Paula Koelemeijer of the University of Oxford. “It is also fascinating to see the links between the movements of plates on the Earth’s surface and structures 3,000 km [1,864 miles] deep in our planet.”

The LLVPs are far from us, but that doesn’t mean we can’t be affected by them. In particular, they prevent heat from escaping from the core to the mantle evenly, which in turn contributes to the convection within the outer core, which drives the geomagnetic field on which we rely. There’s also some tentative evidence they contribute to supervolcanoes.

The study is published open access in the journal Scientific Reports.

Source Link: The Earth Has Two Mysterious Protrusions On Its Core And They’re Not The Same