Since Prototaxites were discovered in the fossil record in 1843, scientists have debated whether they were early land plants, giant fungi, algae, or a whole new kingdom of life. Some of these options have already been ruled out, and they’re now widely considered to have been a type of fungus. However, one species of Prototaxites has been preserved much better than the rest, and the fossil cells don’t resemble living or fossil fungi, leading a team to the conclusion they should be considered part of an extinct lineage.

ADVERTISEMENT

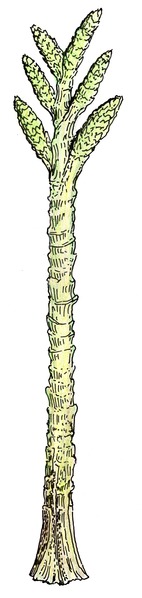

In the early Devonian some 410 million years ago, the action was in the oceans. Life on land was just getting started, and was mostly small. Mosses covered much of the ground and the largest plants of the day grew to just 6 centimeters (2.4 inches). Consequently, at up to 8 meters (27 feet) high, Prototaxites stood out, forming the first counterparts of forests. Their name, which means “early Yew”, has long been known to be wrong, but what they were related to has been a mystery.

Prototaxites taiti was small compared to other Prototaxites, although gigantic by the standards of other lifeforms preserved along with it in the Rhynie chert. It could hold the key to explaining the nature of its larger relatives. The Rhynie chert, located in northern Scotland and protected by a volcanic deposit above, has preserved the fossils within it so well that it is possible to study individual cell walls, something not found in other land-based fossil beds of the era.

In 2018, scientists re-examined a fossil identified as being part of the peripheral region of the first P. taiti discovered. They classified it as being part of the fungal group Ascomycota, whose surviving members include truffles and brewers’ yeast, suggesting some amazing beer-making potential if they’d survived. Given the most widely accepted classification of Prototaxites puts them in the fungi, that didn’t raise too many eyebrows.

Now, however, a different team have examined three P. taiti fossils from the Rhynie chert and reached a different conclusion, although their work is still undergoing peer review.

The authors report several features of P. taiti that do not match Ascomycota, or any other known fungus family, and conclude it was not a fungus at all. Specifically, P. taiti appears to lack chitin or chitosan and beta-glucan, which fungi use as the main structural polymers for their cell walls.

Nor is it the case that the passage of 400 million years has destroyed the evidence of these features. Fungi fossils that lived alongside P. taiti and were also preserved in the Rhynie chert show signs of perylene, a hydrocarbon whose chemical structure looks like four benzene rings joined together. The authors could find no sign of perylene in the P. taiti fossils.

ADVERTISEMENT

Like fungi, P. taiti was composed of tubes at the microscopic scale, and this is one of the reasons the previous study was confident of its fungal status. However, the authors report these tubes have subtle features not seen in any living fungus.

The authors conducted a review of the features they found in P. taiti, and compared them with surviving branches of life and reported each surviving lineage has at least one key feature that is absent in P. taiti. “No extant group was found to exhibit all the defining features of Prototaxites, namely: (1) formation of large multicellular structures of varied tube types; (2) a tube composition rich in aromatic phenolic components; and, (3) a heterotrophic (likely saprotrophic [consuming dead matter]) lifestyle,” they write.

Consequently, they argue, Prototaxites don’t belong to any living lineage, and need to be considered as distinct, a branch of multicellular life that achieved immense success for tens of millions of years, before being entirely replaced. There’s probably a moral in that.

An artist’s reconstruction of P. loganii, one Prototaxites species, which grew very tall, particularly by the standards of the day.

The authors also conclude the other lifeforms that formed an ecosystem with P. taiti and were fossilized in the Rhynie chert were structurally different, and were related to survivors, not the lost lineage. The same may apply to others that accompanied Prototaxites. Whatever these were, they were by far the largest features of their ecosystems, but don’t seem to have had relatives able to fill the niches that formed around them.

ADVERTISEMENT

A preprint of the study is available on bioRxiv while it undergoes peer review.

[H/T: New Scientist]

Source Link: The First Giant Land Organism May Require A New Branch On The Tree Of Life