A new study has found a few odd surprises about the first molecule in the universe, suggesting our models of the early cosmos may need a little update.

Shortly after the Big Bang the universe was a hot, dense soup of particles. After a few seconds, it became cool enough for the first elements to form, mainly ionized hydrogen and helium. Around 380,000 years later, things had finally cooled enough for these ionized elements to combine with free electrons and form the first neutral atoms in the universe.

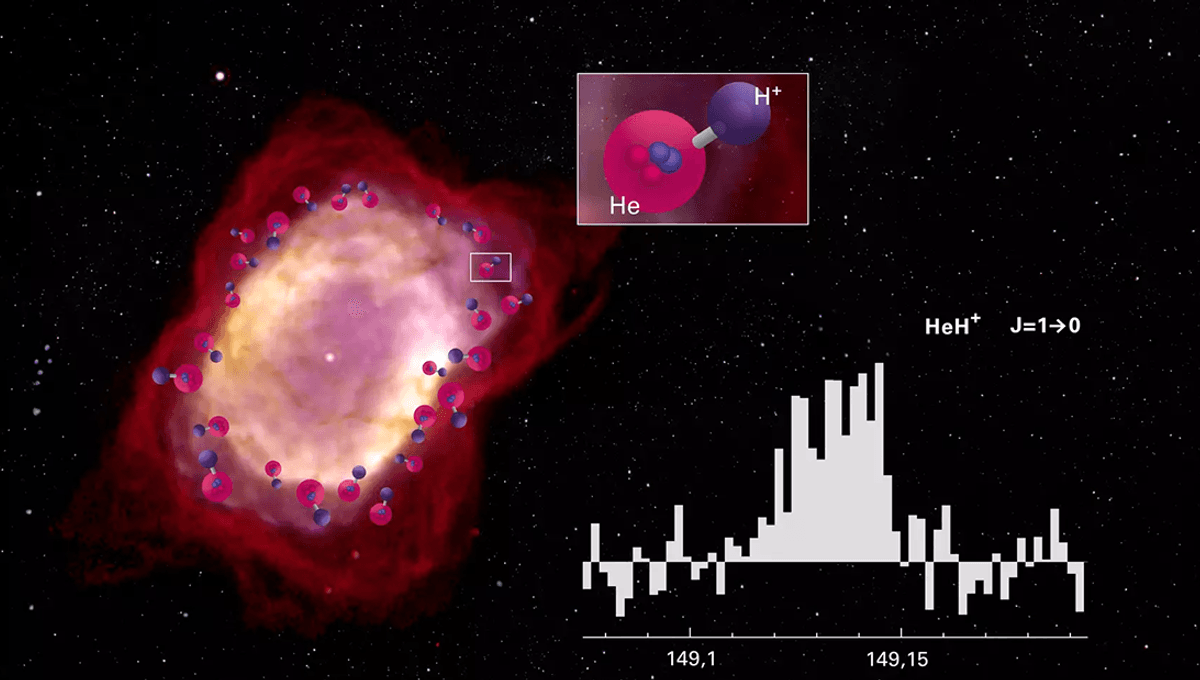

This led to a much more exciting period in the cosmos, facilitating the first chemical reactions. The universe was about to get its first molecule: the helium hydride ion (HeH+), composed of a neutral helium atom and an ionized hydrogen nucleus.

“The first molecules were formed in the radiative association process H+ + He → HeH+ + hν,” the team explains in their paper, “and subsequently other small molecular ions and neutral molecules were formed, among them H2+, H2, H3+, LiH, LiH+, and deuterated variants of those species.”

In this early stage of the universe, HeH+ and H2 (molecular hydrogen or deuterium, the most abundant molecule in the universe) played important roles in cooling protostar clouds enough for them to collapse enough to begin fusion.

“Simulations have shown that the existence of molecules is crucial at this stage. At temperatures below 10,000 K, the level spacing in all of the light atoms is too large to provide the necessary cooling (through photon emission) for a primordial protostar to collapse. Vibrational and rotational degrees of freedom in molecules, on the other hand, enable radiative cooling down to much lower temperature,” the team explains. “With a substantial dipole moment of 1.66 debye, the HeH+ ion becomes a valid cooling candidate.”

In new experiments, the team attempted to recreate the conditions of the early universe, and test whether HeH+ could provide the cooling needed to form the universe’s first stars. The team bombarded the molecule with deuterium at varying temperatures, simulated by varying the relative speed of the beams of particles. To their surprise, and contrary to previous predictions, the reaction rate did not slow as temperatures significantly decreased.

“Previous theories predicted a significant decrease in the reaction probability at low temperatures, but we were unable to verify this in either the experiment or new theoretical calculations by our colleagues,” Dr Holger Kreckel from the Max-Planck-Institut für Kernphysik (MPIK) explained in a statement. “The reactions of HeH⁺ with neutral hydrogen and deuterium therefore appear to have been far more important for chemistry in the early universe than previously assumed.”

These results could have profound implications for our understanding of the early universe, and may even force a bit of reevaluation.

“Measurements at the [cryogenic storage ring] have recently shown that the electron recombination rate is very slow for rotationally cold HeH+ ions,” the team concludes. “Combined with the present finding, it is apparent that reactions of HeH+ with atomic hydrogen are more important for primordial molecular abundances than was previously assumed and that reevaluations of helium chemistry in the early Universe – as well as very recent modeling efforts of HeH+ detections in planetary nebulae – may be called for.”

The study is published in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Source Link: The First Molecules In The Universe Reveal Surprises After Being Bombarded With Deuterium