The ancients knew of five planets, objects that moved against the background stars, if one didn’t count the Sun and Moon. Copernicus revealed the Earth was actually one of these, made different only by our presence here, but the assumption remained that this was all there was, passing comets aside.

Then in 1781, William Herschell shocked astronomers (and delighted generations of 12-year-olds) by discovering Uranus. Suddenly, the possibility there were more worlds to find was on the agenda. Everyone with a telescope wanted to follow in Hershell’s footsteps. In addition to the genuine discovery of Neptune, some started seeing, or erroneously deducing, worlds that weren’t there.

Vulcan

Unlike Uranus, Neptune was not found by chance. Instead, astronomers noticed that Herschell’s discovery was not sticking to its expected orbit. Instead, it was moving as if affected by another gravitational force besides Jupiter, Saturn, and the Sun.

Having helped track down Neptune by calculating the location where such an object should be, the mathematician Urbain Le Verrier turned to the other object apparently defying orbital predictions: Mercury.

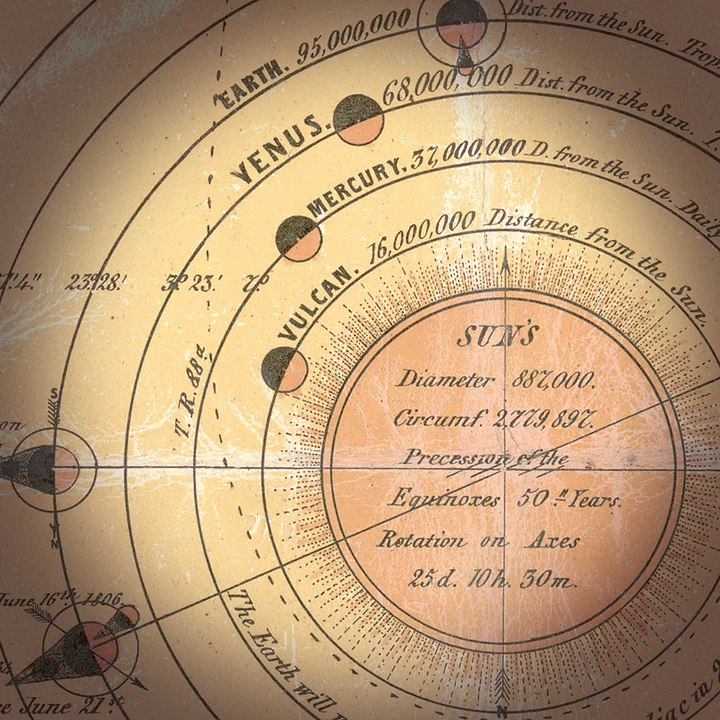

Le Verrier was not the first to make the case that the movement of Mercury’s closest approach to the Sun could be caused by a planet orbiting even closer to the Sun, but he did so with more rigor and credibility. Such an object would naturally be very hard to see since it would probably never appear in a truly dark sky from our perspective, Le Verrier reasoned, explaining why no one had yet found it. In 1859 Edmond Lescarbault claimed to have seen an object transiting across the face of the Sun, as Venus and Mercury do, leading Le Verrier to pronounce his prediction vindicated, and name the planet “Vulcan”.

1846 representation of the inner Solar System including the non-existent planet Vulcan.

Image Credit: Lith. of E. Jones & G.W. Newman – Library of Congress

Subsequent searches failed to find it, however, despite numerous reported transits, and Einstein proved its existence unnecessary, as the warping of space predicted by General Relativity could have the same effect.

Don’t mourn Vulcan too much though, at least Star Trek gave it a sort of immortality by using the name for Spock’s home planet. The category Vulcanoids has been reserved by the International Astronomical Union in case any asteroids are discovered with orbits entirely inside Mercury’s.

Nibiru

Vulcan was speculative, but it looks like solid science compared to Nibiru. First proposed by Zecharia Sitchin in 1976 as the home of ancient astronauts who helped early civilizations do all the things that couldn’t be explained by mid-20th century historians, like building pyramids, Nibiru was promptly debunked by astronomers and historians alike.

Originally proposed as spending most of its time orbiting far beyond Neptune, Nibiru had a brief resurgence about 15 years ago when it became connected to ideas of the world ending in 2012, based on misreadings of the Maya calendar. Some of those who hopped on the bandwagon at the time, even posting photographs on social media of an object they claimed to be Nibiru, placed it between the Earth and Sun, possibly even inside the orbit of Mercury.

There was never the slightest evidence for Nibiru, but sales of books about it did make Sitchin extremely rich. No doubt some of those who revived his ideas also made a fair bit of coin out of gullible followers, so it wasn’t entirely in vain.

Antichthon (Counter-Earth)

There is one spot in the Solar System even harder to observe than the region near the Sun, which we at least get a glimpse of during eclipses. That is the opposite side of the Sun from wherever Earth happens to be. Until the development of space missions, if there had been a planet taking a year to orbit and located 180 degrees from Earth, we wouldn’t have known.

There was never any reason to believe such a planet existed. After all, if any of the other planets had a counterpart opposite to them, we would see it. Instead, all we have found are Jupiter’s Trojan asteroids, sharing its orbit 60 degrees ahead or behind, and a few doing the same thing for Earth and other planets.

Nevertheless, the idea was proposed 2,500 years ago as part of a rather bizarre astronomical model where the Earth, Sun, and a planet called Antichthon all orbited a “central fire” somehow no one had managed to spot.

Post-Copernicus, the idea was revived by UFO enthusiasts looking for a source for flying saucers that wasn’t an improbable distance away. Some science fiction writers made use of the concept, most notably as the location for Superman’s home, Krypton.

Many space probes have now visited locations that should allow them to see Antichthon if it existed: predictably, none have.

Phaëton

While Vulcan, Nibiru, and Antichton proved to be entirely imaginary, another “ghost planet” has a bit more substance to it. Astronomers had long noticed a pattern in the orbits of planets, with the distance between each approximately doubling, aside from a gap between Mars and Jupiter. This was eventually codified in Bode’s Law.

A group that called themselves the Celestial Police set out to fill the gap by finding an expected missing planet with an orbital radius about 2.8 times that of the Earth’s. They were rewarded with the discovery of dwarf planet Ceres, almost perfectly placed, but disappointingly small. Numerous other asteroids followed, many with orbits quite similar to Ceres, but smaller still.

Both hemispheres of Ceres as seen by the Dawn Spacecraft. The biggest member of the asteroid belt, but still not a planet.

Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UC:A/MPS/DLR/IDA

This led to the idea that there had once been a planet in this orbit, provisionally designated Phaëton, which had met with some unfortunate fate, possibly a warning to Earth.

Once again, the idea has proven popular with those not overly fond of evidence, and a handy premise for science fiction writers.

We now know that Jupiter’s gravity prevented a planet from forming where the main asteroid belt now lies, and therefore Ceres, Vesta, and the rest were never part of a common planet. Somewhat surprisingly, given how many asteroids there are in the belt, even if they had all managed to combine, they would still have been too small to count as a planet using current definitions.

Pluto

Inevitable controversy here, as many people continue to resist the 2006 vote of the International Astronomical Union to demote Pluto from planetary status. There’s no point rehashing the debate here. If you’re not already familiar you can read about it here.

Planet X

For well over a century, a planet beyond Neptune has been proposed, driven initially by unexpected features of the orbit of Neptune itself, and then by patterns in the orbits of comets and asteroids. Pluto was initially thought to be what astronomers were looking for but was soon recognized as being far too small.

The sizes and orbits of the proposed planets have varied with time, from objects of similar mass to the Earth up to giant worlds much further from the Sun. One version, Nemesis, was proposed to have a 26-million-year orbit. There’s a fair chance at least one of these ideas is real, but it’s unlikely all of them are, so somewhere among the mix there’s almost certainly a ghost, possibly several.

Source Link: The “Ghost Planets” That Turned Out Not To Exist