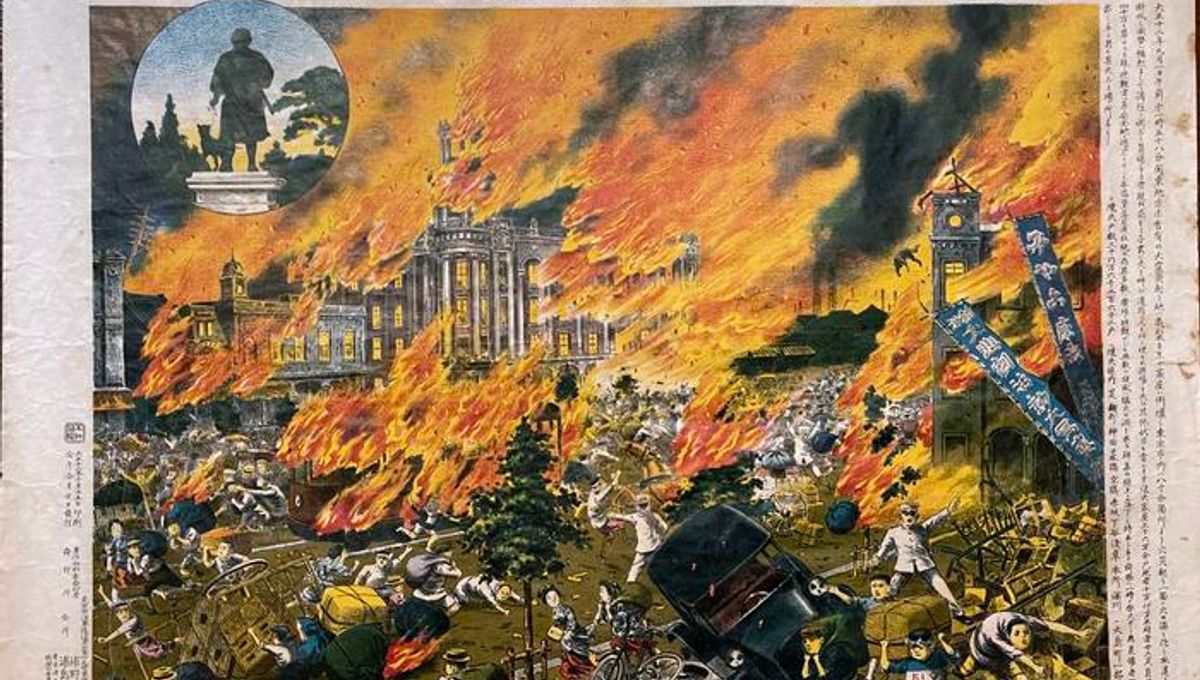

On September 1, 1923, the area surrounding Tokyo, Japan, was struck by a magnitude 7.9 earthquake. The Kantō earthquake, as it is now known, represents one of the deadliest natural disasters in history, killing around 105,000 people. However, 90 percent of those deaths were not caused by the quake or collapsing buildings, but by fires that broke out as a consequence.

This story of conflagration – where fire destroys significant amounts of land or property – holds important lessons for emergency response teams, city planners, and earthquake scientists today, a new research paper has stressed.

1923 – a city of flame

According to the paper, the historical fires caused by the Kantō earthquake had been anticipated by contemporary seismologist, Imamura Akitsune, an assistant professor of seismology at Tokyo Imperial University. Imamura had theorized that a large earthquake was due to hit the Tokyo region in 1905 and warned that citizens would be exposed to raging fires triggered by its activity.

To prevent disaster, Imamura suggested certain measures, such as abolishing kerosene lanterns and creating setbacks between new buildings to limit the spread of potential flames.

However, as is often the case with these things, Imamura’s warnings were ignored and even ridiculed by his fellow seismologists. In particular, Ōmori Fusakichi, a senior colleague, refuted Imamura’s claims based on the belief that earthquakes rarely occur in stormy or windy weather, which meant there would not be sufficient wind to spread any fires caused by such an event.

However, Ōmori was wrong. At two minutes to noon on September 1, 1923, as people across Tokyo were preparing to cook their lunches, the ground started to shake, causing their stoves and grills to fall over. Within 30 minutes, there were already 100 fires across the city that was, as Charles Scawthorn, a researcher at the Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center, University of California at Berkeley, said in a statement, “largely built up of cheek-by-jowl light wood and paper housing.”

“Under ordinary circumstances, the Tokyo fire department would not have been able to address all these fires, but compounding the situation were hundreds of breaks in the water mains, so that firefighters were largely powerless,” Scawthorn added.

In some instances, the fires merged together to such an extent that they created fire whirls or cyclones, which devastated everything in their path.

In a new paper, Tomoaki Nishino of the Disaster Prevention Research Institute at Kyoto University explored the impact of the fires and modeled their spread, especially in relation to wind direction and velocity. Nishino also looked at how urban fires might spread in Kyoto City if a quake of a similar magnitude struck along the Hanaore fault.

“Large fires after an earthquake depend not only on the strength of the shaking, but on other conditions like the weather and built environment,” Nishino explained. “If the area consists of many fire-resistant buildings, or a low density of buildings, the conflagrations would not occur.”

“The collection of those conditions is less frequent than strong shaking, so the devastating regional impact of fires following earthquakes is less frequent compared to that of earth shaking,” he added. “But there can be a time when the number of simultaneous fires overwhelms firefighting capabilities.”

The costs and the lessons

The researchers found that less than 5 percent of the literature covering the Kantō earthquake actually examines the fires in any detail, despite the devastation they caused. According to their work, recent calculations suggest the fires caused a total of ¥ 1.5 billion (over $10 million) in damages – the national budget for 1923 was ¥ 1.37 billion (around $9.3 million).

Rather than calling it the Kantō Daishinsai or Great Kantō Earthquake Disaster, the authors argued the event should more accurately be referred to as Kantō Daikasai or the Great Kantō Fire Disaster.

The threat of earthquake conflagration is still real today. Places with strong seismic activity and large inventories of wood-framed buildings, such as the US West Coast (including Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle), Japan, and parts of New Zealand, need to consider fire prevention and responses as part of their earthquake management plans.

The Kantō quake had profound impacts on Japan’s approach to earthquakes, especially to protect children.

Imamura “invested so much as a seismologist in public education” after 1923, Janet Borland, a historian at the International Christian University in Tokyo, explained, “including pushing for the very first earthquake safety lesson in the Japanese school curriculum.”

“He convinced the Ministry of Education officials, ‘we’re an earthquake nation, we need to teach our children what to do when an earthquake strikes.’”

In recent years, the threat of earthquake-related fires has led Japan to install seismic shutoff valves on gas meters throughout the country. But further analysis and action is needed to contend with the dangers such fires pose.

As Scawthorn explained, “Imamura foresaw and foretold – science can warn, but economics, politics and resources must be mobilized if a warning is to have any effectiveness.”

The study is published in the journal Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America.

Source Link: The Great Kantō Fire That Killed Over 105,000 People In 1923