In 1858 a catastrophic pollution event descended upon London as its sewer-filled streets and waterways built up to create “The Great Stink”. The Thames was and remains a central feature of England’s capital, but back then it wasn’t filled with seals, seahorses, and eels, like it is today. Back then, it was basically a big toilet.

The Thames had become heavily polluted with raw sewage and industrial waste as a result of a huge amount being produced in the bustling city while there wasn’t anywhere to properly dispose of it. “Night soil men” would collect some of it for use in agriculture, but a lot was left on the street or ditched in waterways. Even those with the rare commodity of a flushing toilet weren’t much better off, as the raw sewage just went into the Thames untreated. All in all, it made for an eye-watering aroma.

Things got considerably worse in the summer of 1858, when hot weather and a parched Thames River concentrated the smell. It got so bad that Parliament considered moving location because debates couldn’t endure the stench, and in the Houses of Parliament curtains were being soaked in in a type of bleach to try and mask it.

In the two decades preceding that fateful summer, cholera cases had been on the rise, leading many to suspect that the increasingly fetid air was to blame. In truth, as a waterborne disease cholera was spreading as a result of people ingesting contaminated water. It was happening a lot since some of the poorest communities had no choice but to dip for water in the Thames, leading to outbreaks like one in 1848 that’s said to have wiped out around 1,500 of the waterfront population in Lambeth.

Fearing the polluted air was to blame, officials agreed The Great Stink had to go.

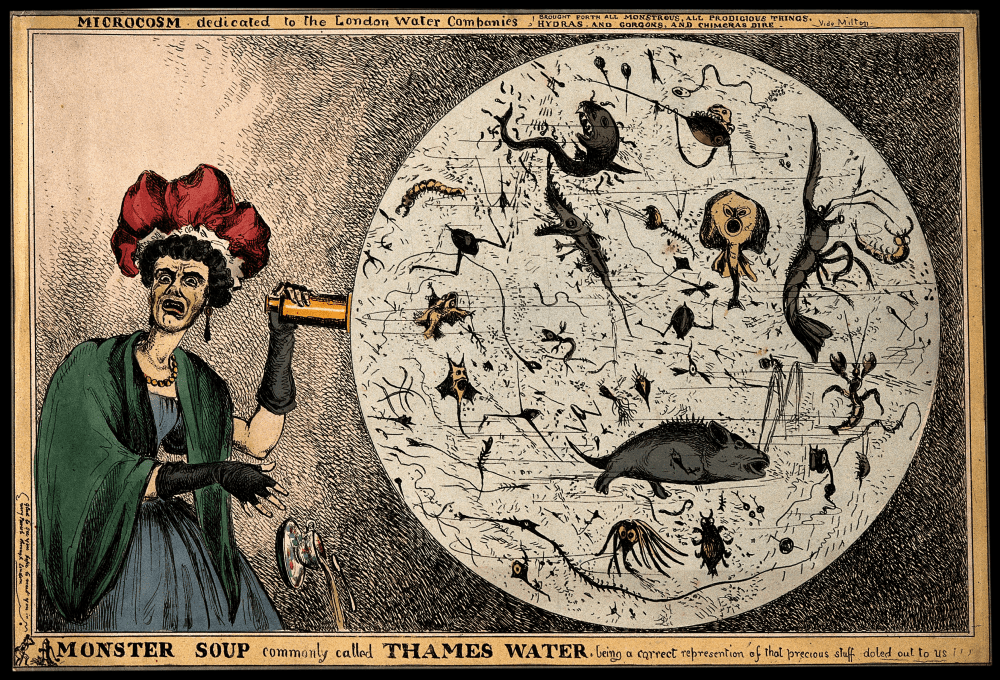

The water was so famously polluted that it became known as Monster Soup.

Sir Joseph Bazalgette would lead the transition to a greener London, establishing a sewer system that could carry human waste further out towards the Thames Estuary. The idea was that getting it closer to the sea would sweep away the bad times with the tide, but it alone wouldn’t be enough to stop The Great Stink.

Bazalgette also wanted to establish embankments along the river to conceal the newly built sewers, but it wasn’t a hit with everyone as building meant demolishing streets close to the water. Businesses and communities were turned to rubble in the process, but it did come with the added benefit of acting as a flood defense.

Pumping stations along the embankment facilitated the sewage’s journey out to sea, leading to a new stretch of 1,600 kilometers (1,000 miles) of new sewer. In total, the scheme cost around £2,500,000 ($3,100,000) which is the modern equivalent of nearer £300 ($375) million, explains Historic England.

In the 1950s the Thames was so polluted it was declared “biologically dead,” but thanks to Bazalgatte’s scheme it’s not only recovered, but is home to all manner of marine animals including seahorses, eels, seals, and the occasional wayward cetacean.

London’s population has boomed in the last 70 years, applying new pressures to the city’s sewers, but a new project set to be completed in 2023 is upgrading the city’s waste management. The “Super Sewer” hopes to tackle the issue of overflowing sewage that occurs when it rains, helping to keep London’s humans and wildlife happier and healthier.

We can all drink to that.

Source Link: "The Great Stink" Engulfed London In A Cloud Of Fetid Air Back In 1858