The Wallace Line has shaped species diversity across Asia and Australia but, the thing is, it doesn’t actually exist. It’s completely imaginary, and yet its influence on species evolution is very much real.

Animals – and plants too, although less obviously – look very different on either side of the line, which might make sense if this were some physical boundary we were talking about. But it’s not: it’s invisible. So, what is going on?

What is the Wallace Line?

The Wallace Line refers to an imaginary frontier, which effectively separates the faunal regions of Asia and Australia. To the west of the line, you’ll find species including elephants, tigers, rhinos, and orangutans, but on the eastern side, these are nowhere to be seen. Instead, you’ll find marsupials, monotremes, and maybe the odd Komodo dragon.

It is what is known as a biogeographic boundary: a border between two regions that are distinct in their biodiversity.

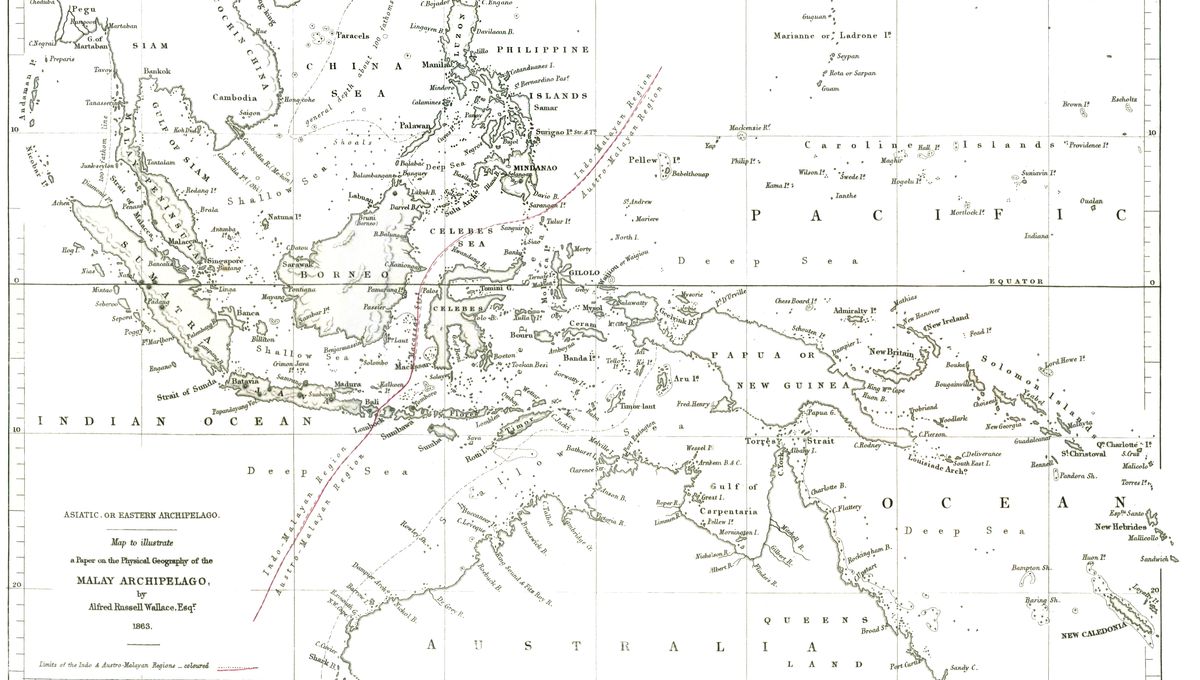

The line was first drawn in 1859 by British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, after whom it is named. Wallace conceived the theory of evolution independently of Charles Darwin, to whom it is often solely credited, but was beaten to the punch when Darwin published his findings in On the Origin of Species.

“The problem then was not only how and why do species change, but how and why do they change into new and well defined species, distinguished from each other in so many ways; why and how they become so exactly adapted to distinct modes of life; and why do all the intermediate grades die out (as geology shows they have died out) and leave only clearly defined and well marked species, genera, and higher groups of animals?” Wallace wrote in his autobiography.

Despite being overlooked when it comes to evolution, Wallace’s travels in Indonesia have ensured his infamy elsewhere, as the first to hypothesize the Wallace Line.

Where is the Wallace Line?

The Wallace Line weaves its way through the Malay archipelago, running from the Indian Ocean through the Lombok and Makassar Straits, all the way to the Philippine Sea.

Its location has been tweaked several times in the 164 years since it was first proposed. Just three years ago, for example, it had to be redrawn after Christmas Island threw up a curve ball: although it lies nearer to islands west of the line, half of its land mammals and reptiles have genetic heritage from the eastern side.

What’s going on?

The secret of the Wallace Line lies in plate tectonics, which wasn’t validated as a theory until 50 years after Wallace’s death.

The Malay Archipelago is one of the most complex tectonic regions in the world, home to several tectonic plates, which are responsible not only for its many volcanoes but also its strange distinction in biodiversity.

Once upon a time, the area around the Wallace Line was made up of two continuous land masses. Today, they are known as the Sunda and Sahul paleocontinents and are much closer together than they were 25 million years ago.

Over time, the two have drifted closer together, bringing with them very different species that spent eons evolving in very different environments and look very different as a result.

What is Weber’s Line?

To confuse things further, there’s another line in the mix: Weber’s Line. Weber’s Line was proposed in 1900 as an alternative to Wallace’s Line. It is another hypothetical boundary that marks the difference between species found in Australia and Southeast Asia.

Source Link: The Imaginary (But Also Real) Line That Divides Species In Asia And Australia