A tiny kingdom that became an expanding republic, finally peaking as a vast Empire, the city and culture of Ancient Rome have had a profound effect on life today. This so-called “eternal city” is littered with relics and ruins (and truly, so much porn) that date back nearly three full millennia – and yet, there are some things about ancient Roman life that have been entirely lost to time.

There’s the question of how they made their concrete, for example – an engineering feat we’ve yet to fully understand. There are all those little dodecahedrons that keep turning up all over the place, despite no written record of them ever being found.

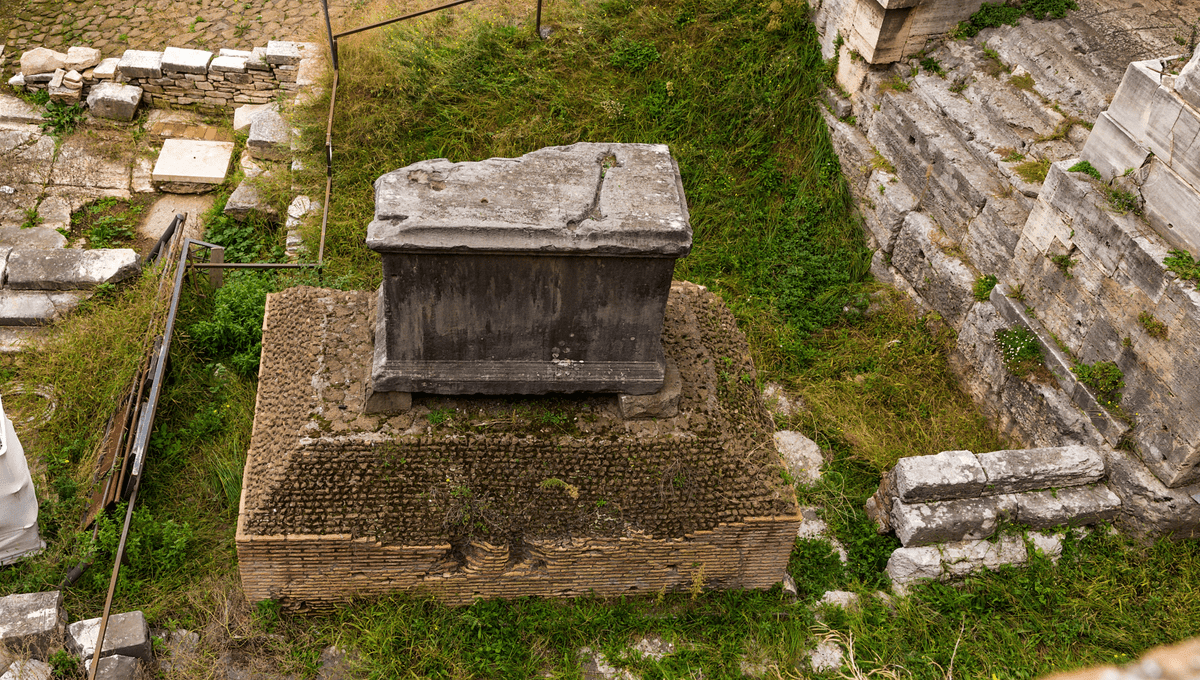

Then there’s the Lapis Niger. Translating to the “black stone” – these things always sound more impressive in Latin – the Lapis Niger is an ancient shrine, found in the center of the Roman Forum and dating back as far as the ninth century BCE. It was treated with great reverence – and no small amount of trepidation – by the city’s early residents, who associated its location with bad luck and its destruction with a terrible curse.

But what exactly is it? The core of the shrine is a cone of volcanic rock and a portion of a square pillar marked with an inscription that looks more like Greek than the Old Latin it actually is. Surrounding that, there is – or at least, there was once – a U-shaped altar, which may have originally come with stone lions to guard the monument. Outside of that comes the “black rock” itself: blocks of black marble paving squares, fenced in by a wall of white marble.

As for why it exists, though – well, it’s a testament to just how old and shrouded in mystery the Lapis Niger is that, were we able to go back in time and ask an Ancient Roman what it was for, they probably wouldn’t know either.

Most explanations for the rock’s appearance, though, drew on the mythology of Rome’s founding: “most people say that Romulus was buried [there],” ancient commentators on the first century BCE poet Horace recorded, “and that this was the reason that the two lions were placed there, just as they may be seen to‑day guarding graves.”

Now, not to impugn the Romans’ record keeping, but this is unlikely: Romulus was the legendary first king and founder of Rome who, along with his twin brother Remus, was supposedly abandoned on the banks of the River Tiber until an actual wolf found them and decided to nurse them herself in a nearby cave. The pair were said to be the sons of a Vestal Virgin (or possibly princess) and the god Mars, and saved from drowning as babies by the river god Tiberinus – you get the picture. To sum up: the brothers probably didn’t really exist at all.

Equally shaky is another theory, put forward by first-century BCE historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus, that “the stone lion, which is in the noblest place in the Roman Forum… was a monument for Faustulus, who was buried on the spot where he fell in battle.” If true, that would make the Lapis Niger the resting place of Romulus’s foster father: Faustulus was, according to myth, a shepherd who found the twins with their adopted lupine mother and decided to take them home with him instead.

Sources are split on whether this putative burial was on purpose or by fluke: the Roman teacher Sextus Pompeius Festus, writing during the later 2nd century CE, claimed that the Lapis Niger “was intended to serve as the grave of Romulus, but this intention was not carried out, and in the place of Romulus his foster-father Faustulus was buried.”

And yet others had still more theories. Dionysius, in another place, mentions Tullus Hostilius, the more-real-than-Romulus-but-still-pretty-fuzzy third king of Rome, as being the one interred beneath the Lapis Niger. Festus, meanwhile, suggested it may have been Tullus’s grandfather Hostus Hostilius, a warrior said to have fought alongside Romulus against the Sabines.

Of course, there’s one very good reason why none of these possibilities are likely: the fact that the Lapis Niger dates to roughly the sixth century BCE. This is extremely old – in fact, the altar underneath the marble contains one of the earliest known Old Latin inscriptions – but it’s still a couple of hundred years later than any of these figures are said to have lived.

So, will we ever know who was buried under the Lapis Niger? Well, the good news is, we have something all those ancient writers didn’t: 3D laser scanning technology. Back in 2020, a team of archeologists set out to fully document the tomb marked by the Lapis Niger – and what they found inside may disappoint any mythologically-minded residents of the ancient city.

After close to three millennia of mystery, the sarcophagus resting under this monumental black shrine was … empty. No Romulus; no Faustulus; no anybody. Was it all just one big misunderstanding?

Well, leave it to archeologists to get excited about an empty old box. “The sarcophagus shows that the way in which the Romans mythologized the founding of the city was even more complex and rich than we thought,” Darius Arya, an archeologist and the head of the American Institute for Roman Culture, told The Telegraph at the time.

“They were giving significance to the foundation myth not just in the time of Julius Caesar but way back in the 6th or 7th centuries BC, just as Rome was getting started,” he said.

In other words: to the ancient Romans, it probably wouldn’t have mattered that the tomb was empty. It could still commemorate Romulus – who was said to have vanished into the sky to become a god after he died in any case, and so probably didn’t leave much in the way of remains to bury.

Instead, the area around the Lapis Niger would have been “highly symbolic,” Alfonsina Russo, director of Rome’s Colosseum Archaeological Park, told Reuters – a place where pagan rituals and sacrifices were held over many centuries, and locals commemorated their city’s mythology.

“This is not the tomb of Romulus per se,” Russo explained to The Daily Beast. “[But] it is a place of memory where the cult of Romulus was celebrated.”

Source Link: The Lapis Niger Was A Mystery Even In Ancient Times. The Truth Was Even Stranger