On the bottom of the seafloor near Colombia, surrounded by fish and three centuries of sediment, there sits a shipwreck loaded with millions, perhaps billions, of dollars worth of treasure.

Attracted by the promise of glory and gold, the sunken remains of the San José have charmed the eyes of many contenders – countries, governments, tribes, and private diving companies – who claim they are the rightful owner, sparking endless lawsuits and international spats. As valuable as its riches may be, monetary fortunes are only the beginning of this relic’s value.

The Colombian Institute of Anthropology and History announced in May 2024 that it was launching a scientific and cultural research project to learn about the sunken San José galleon. There have even been rumors its recovery could occur this year, which is why the dispute over ownership is hotting up. Colombia’s President Gustavo Petro has made the shipwreck’s recovery a top priority for his administration before his term ends in 2026, reportedly telling his minister to “pick up the pace.”

Ever-surrounded by controversy, the story of San José appears to be approaching its final chapter – but don’t expect a quiet conclusion.

The San José was a three-masted galleon treasure ship under the command of the Spanish Navy that stretched around 45 meters (150 feet) from bow to stern. Known as the “holy grail” of shipwrecks, it’s commonly cited that $17 billion worth of relics are among its ruins, just waiting to be discovered. Some believe that figure is overinflated – perhaps to fuel further public interest. Either way, most agree it’s one of the most valuable historical shipwrecks ever known.

To understand how it amassed such affluence, we must look back to the empires and bloodshed of the 18th century.

The galleon set sail in 1698, a tumultuous time in world history when European powers were vying for control of global trade and the Americas. To fuel and fund their empires, an ungodly amount of resources – silver and gold, precious stones and tobacco – were looted from their territories across America and brought to Europe.

Cutthroat competition over the Atlantic became turbo-charged with the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714) when Bourbon Spain and France was pitted against Habsburg Spain, the Holy Roman Empire, Great Britain, the Dutch Republic, Prussia, and Portugal. This multi-dimensional conflict is sometimes called “the first world war of modern times” because campaigns were fought all across the world, as well as the high seas.

Commodore Wagers’s flagship attacked the San José, but within an hour it exploded. It didn’t go down slowly. It went down really quickly.

Dr Ann Coats

“Britain and the other allies were challenging Spain’s control of Europe, but also their control of world trade. The war involved the Americas, the Atlantic Europe, the Mediterranean, Africa, and the East Indies. It was the whole world,” Dr Ann Coats, an Associate Professor in Maritime History at the University of Portsmouth, told IFLScience.

“These treasure ships were being preyed upon by the British Royal Navy, because they wanted to capture the treasure ships for themselves. That money would be really useful to fund the Navy, the war, and everything else.”

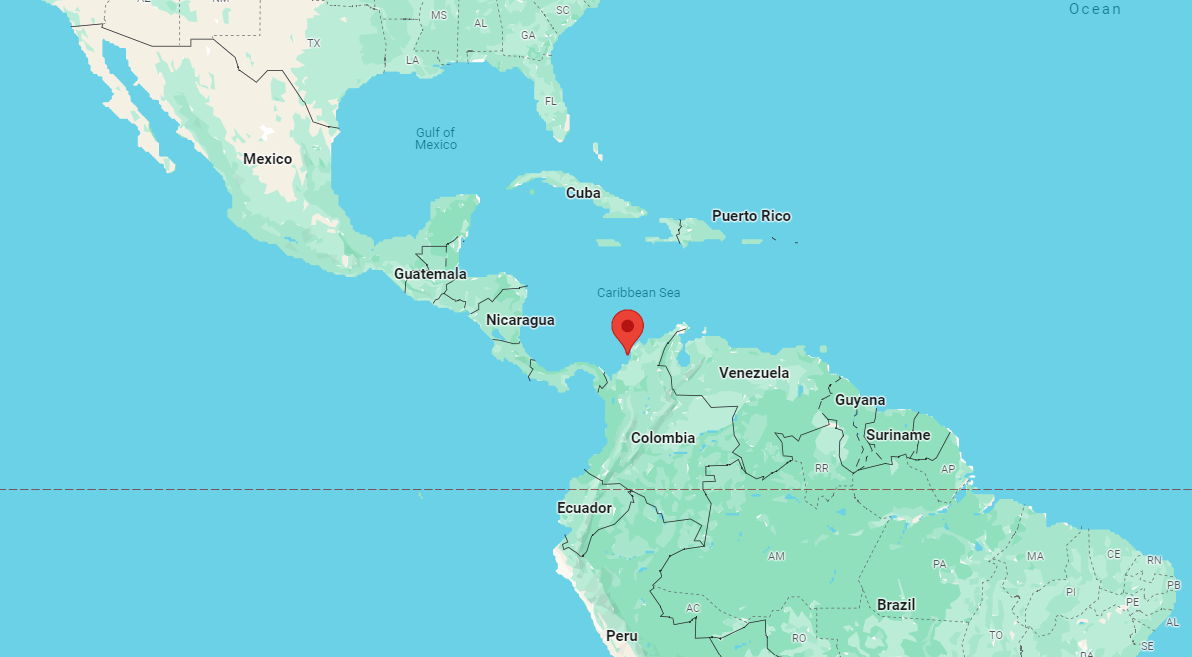

The San José sunk in battle off Barú Island, marked here in red.

Image credit: Google Maps

In the spring of 1708, the San José was sailing as the flagship of a treasure fleet from Panama when it ran into a British squadron under Charles Wager who had been patiently waiting for its arrival, no doubt aware of the wealth onboard. The British attacked as it passed Barú Island, hoping to capture the booty-loaded fleet, but there was an explosive hiccup in the plan.

“Commodore Wagers’s flagship attacked the San José, but within an hour it exploded. Either there’d been an accident and the ammunition caught fire or the shooting penetrated the ammunition store and it caught fire,” said Coats.

“It didn’t go down slowly. It went down really quickly.”

Along with the ship, its stacks of looted treasure sunk too. The ship’s long-lost cargo remained unseen for around 300 years until advances in submersible technology and seafloor exploration opened up the possibility of viewing and even recovering the wreckage. In 1982, a salvage group called Glocca Morra Company claimed to have found the shipwreck of San José. The company was later taken over by a group of American investors called Sea Search Armada.

Another image from 2015 project by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution showing ceramics and other artifacts.

Image credit: Colombian Ministry of Culture

They provided the coordinates of the shipwreck to the Colombian government with the understanding that it would split the findings. However, Colombia disputed the company’s claim and refused to strike a deal. Sea Search Armada tried to sue the government several times, unsuccessfully.

Things became even messier in 2015 when the Colombian government said it had found the shipwreck at a different location. The country’s president Juan Manuel Santos affirmed the news, tweeting: “Great news: We found the galleon San José! Tomorrow I will give the details at a press conference from Cartagena.”

However, Sea Search Armada doubted the legitimacy of this claim and has reportedly suggested it’s a scheme by Colombian officials to dismiss their longstanding claim to share the immense wealth.

Several others believe they’re entitled to a slice of the pie too. Spain has claimed ownership of the wreck since the San José was a Spanish ship, while Peru and Panama believe it’s theirs because the goods were originally stolen from their lands. The Qhara Qhara, an indigenous group native to Bolivia, has also staked a claim on the grounds that their ancestors were forced to harvest the shipwreck’s treasure from their native homeland.

At the risk of sounding misty-eyed, there’s much more to the San José shipwreck than money. If the shipwreck is successfully studied and recovered, historians and marine archeologists stand to learn an amazing amount about this period of history and the people who shaped it.

If it hadn’t been full of gold, there probably would have been no impetus to even look for the wreck. It’s purely because of the money. But the money isn’t what makes it rich.

Dr Ann Coats

A taste of this came in 2015 when the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution explored the shipwreck site with the help of an autonomous underwater vehicle. At a depth of 600 meters (1,968 feet) below the surface, the robot-sub collected imagery of artifacts from the ship, including bronze cannons ornately engraved with dolphins, ceramic vessels, and dozens of teacups.

Other historical shipwrecks have proved to be a gold mine for excavators – in more than one way. The Mary Rose, a giant carrack of the English Tudor Navy, sunk in 1545 off the southern coast of Britain on its maiden voyage. Following years of work, it was recovered from the seabed in 1982 amidst a groundbreaking maritime salvage operation.

The Mary Rose shipwreck was recovered and now lies in the Mary Rose Museum in Portsmouth’s historic dockyard.

Image credit: Dave Colman/Shutterstock.com

It’s been a massively expensive project, but it still offers new scientific and historical insights today. In 2019, a genetic study of the isotope analysis and DNA testing of skeletons from the wreck showed the crew was surprisingly diverse for the 16th century, including people from across Europe and possibly even Africa.

The San José shipwreck is unlikely to provide such vivid insights since it was destroyed in a fiery explosion, but it still has much to offer.

“There’s a very close parallel to Mary Rose because they took the opportunity of conserving, displaying, and interpreting everything so that people can go and look at these stories,” Coats told IFLScience.

“If [the San José shipwreck] is so wealthy, then they can surely put aside some money for the cultural interpretation. What they spend on interpreting it is going to be a fraction of what they’re going to gain from all this wealth – that’s a positive,” she added.

Ultimately, the promise of money is what has fueled curiosity around the San José shipwreck. Now there’s serious talk of recovering it, we can only hope it doesn’t just become a lucrative cash cow.

“If it hadn’t been full of gold, there probably would have been no impetus to even look for the wreck,” concluded Coats.

“It’s purely because of the money. But the money isn’t what makes it rich.”

Source Link: The Messy Fight Over Who Owns The $17 Billion Shipwreck Of The San José