Putting telescopes on the far side of the Moon, safe from Earthly interference, is one of the biggest reasons to revive lunar missions. However, the Moon has its own challenges, including a 300°C (530°F) temperature range, leading to some doubt about how long instruments would survive. To test the waters, or lack thereof, the LuSEE-Night experiment aims to land a small radio telescope on the surface and see how it manages.

Astronomers are getting ever-cooler toys instruments to play work with, but it’s not all progress. Skyglow has made optical research unviable from many parts of the world, and even mountain-top telescopes are increasingly affected by satellites. Meanwhile, radio telescopes must avoid certain parts of the spectrum for fear of being deafened by their local FM station. Even then, they can be affected by microwave ovens in the tea room.

Placing telescopes in space is part of the solution, as Hubble and the JWST have proved, but big dishes required to capture longer wavelengths need more. Having a stable platform like the Moon would help, and using its bulk as a buffer against all those pesky Earth signals is a bonus. A conveniently sized crater could support a dish, just as occurred for decades at Arecibo.

A lunar radio telescope would be used to study hundreds of problems existing instruments can’t quite manage, but the highest priority is investigating the Cosmic Dark Ages. To astronomers, this does not refer to the period between the fall of the Roman Empire and the Renaissance, but the period from the production of the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) to the appearance of the first stars.

The major radio signals from this era are expected to be found between 0.5 and 50 megahertz, which are effectively impossible to detect from Earth. Not only is the chatter from human-produced signals too loud, but the atmosphere is too distorting at these wavelengths. Complicating matters further, we are looking not for extra radiation, but dips where Dark Ages hydrogen absorbed stretched CMB.

Such a project would be breathtakingly expensive. Certainly not something you’d want to go wrong. The Lunar Surface Electromagnetics Experiment-Night (LuSEE-Night) is a pathfinder project using 3-meter (9.8-foot) antennae, intended to test the technology on an affordable scale and see where the pitfalls lie.

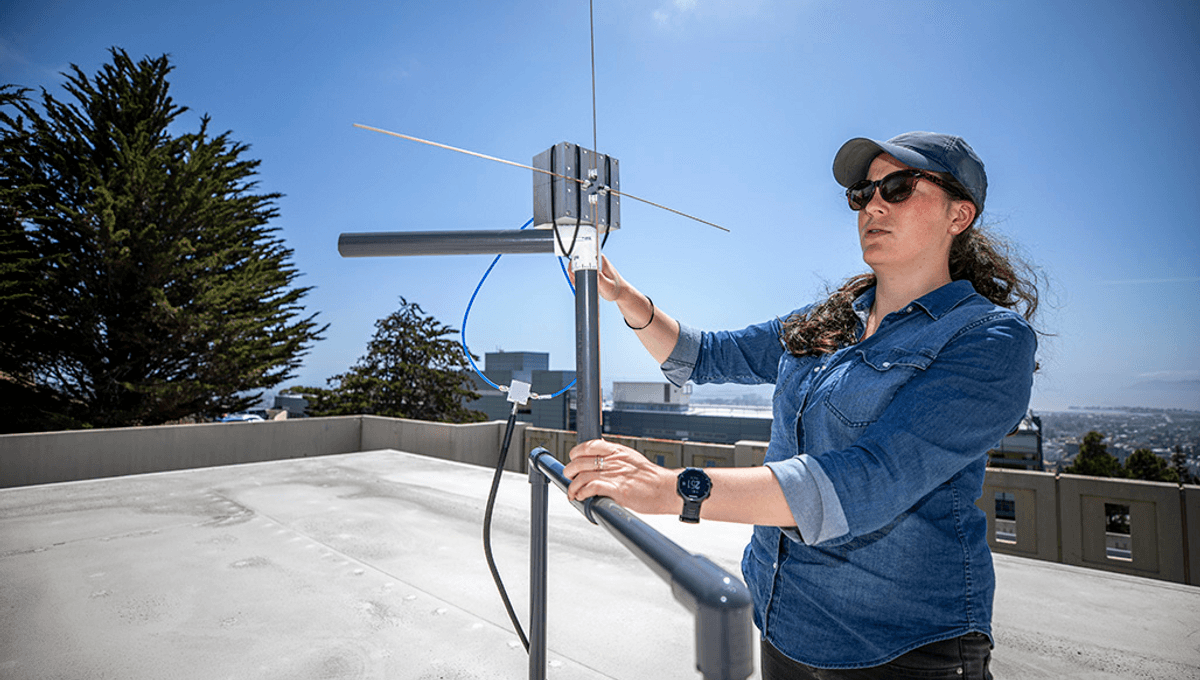

“If you’re on the far side of the moon, you have a pristine, radio-quiet environment from which you can try to detect this signal from the Dark Ages,” said Dr Kaja Rotermund of Berkeley Lab in a statement. Rotermund is part of the team building the LuSEE-Night antenna which, all going well, will be deployed on the lunar surface in 2025.

Even the site for LuSEE-Night has been chosen. Credit: Google Earth

“LuSEE-Night is a mission showing whether we can make these kinds of observations from a location that we’ve never been in, and also for a frequency range that we’ve never been able to observe.” Rotermund added.

The second half of the project’s name reflects the fact that interference from the Sun means LuSEE-Night will only be able to explore the Dark Ages when it is actually dark. Fortunately, on the Moon that lasts for two weeks at a time.

This means the instrument Rotermund is building must operate at -175°C (-280°F). Worse still, it will have to survive temperatures of 140°C (280°F) during the lunar day, even if it won’t be working at the time.

“The engineering to land a scientific instrument on the far side of the moon alone is a huge accomplishment,” said team leader Dr Aritoki Suzuki. “If we can demonstrate that this is possible – that we can get there, deploy, and survive the night – that can open up the field for the community and future experiments.”

That won’t be the end of the problems, however. The same lunar bulk that keeps out unwanted radio signals from Earth also prevents communication. Every instruction will need to be beamed to a satellite in lunar orbit, and then sent to the lander when the orientation is right.

If it all works, however, astronomers can start planning something bigger.

Source Link: The Moon’s Far Side Holds The Future Of "Dark Ages" Radio Astronomy