The oldest government computer still in operation today is over 25 billion kilometers (15.5 billion miles) from Earth, and despite well-documented issues, it still runs far better than we could expect.

While you may rush out to buy the latest hardware necessary to run the latest computer games, governments and large organizations can end up hanging onto older tech for far longer. For instance, it’s not been long since the US military stopped using floppy disks to control its nuclear weapons, and US air traffic control systems still use a combination of floppy disks, paper printouts, and Windows 95 to land aircraft full of passengers.

The oldest US government computer still in operation goes back far beyond Windows 95, and was created not long after the floppy disk’s invention in 1971. The reason why it is still in use all these years later is that it works surprisingly well, and it’s difficult to upgrade hardware from 167 astronomical units (AU) away, with one AU being the distance between the Earth and the Sun.

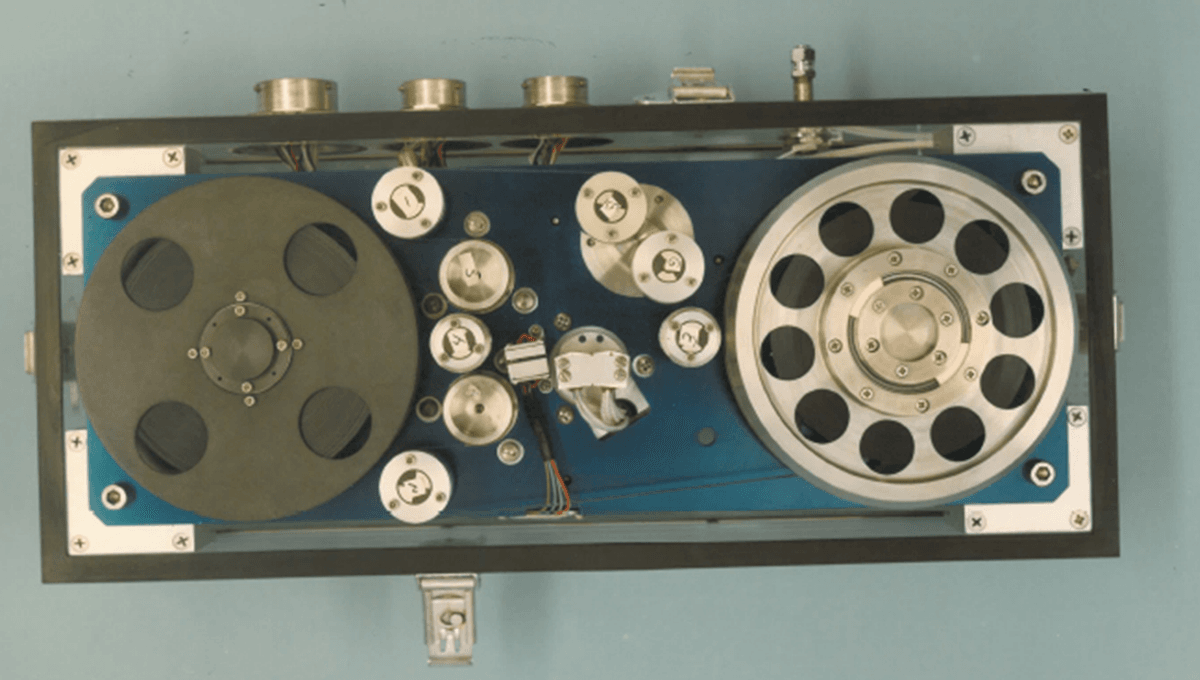

As you may have guessed, the oldest working US government computers are on board the Voyager spacecraft. These probes, launched in 1977, each contain six computers in total, comprised of three different types of computer. These are the 18-bit Computer Command System, the 16-bit Flight Data System, and the 18-bit Attitude and Articulation Control System. All three were built by General Electric to NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory specifications, and each craft got two of each computer as a backup, should anything go wrong with the first.

These computers are not exactly speedy, even if you don’t take into account the 23+ hours it takes for a signal to travel to the spacecraft from Earth.

“The master clock runs at 4 MHz but the CPU’s clock runs at only 250 KHz,” NASA explains. “A typical instruction takes 80 microseconds, that is about 8,000 instructions per second. To put this in perspective, a 2013 top-of-the-line smartphone runs at 1.5 GHz with four or more processors yielding over 14 billion instructions per second.”

While that doesn’t sound great by modern standards, the memory is more of an issue. In total, the spacecraft can store about 68 kilobytes on its 8-track digital tape recorder. That’s around the size of a single JPEG, and yet NASA is able to use this tiny storage to get back useful science data from beyond the Solar System’s 30,000-50,000 Kelvin “wall”. To do so, the computers write over the old data with new data as soon as the old data has been transmitted back to Earth. This is how Voyager sent back images of its encounters with planets on its way out of the Solar System, as well as its final view before it shut down cameras to preserve power for other scientific instruments.

“In order to allow real-time transmission of video information at each encounter, the flight data subsystem can handle the imaging data at six downlink rates from 115.2 to 19.2 kbps,” NASA explains. “The 115.2-kbps rate represents the standard full-frame readout (at 48 seconds per frame) of the TV vidicon. Under normal conditions, that rate was used at Jupiter. Full-frame, full-resolution TV from Saturn can be obtained by increasing the frame readout time to 144 seconds (3:1 slow scan) and transmitting the data at 44.8 kbps. A number of other slow scan and frame-edit options are available to match the capability of the telecommunications link.”

While the computer remains the same as when it was launched – try getting an IT worker to upgrade your graphics card at the edge of the Solar System – it has received a software update in the interim. After the Voyager 1 spacecraft began sending back useless, incomprehensible data, NASA scientists realized that part of the flight data system computer’s software had become corrupted.

“Unable to repair the chip, the team decided to place the affected code elsewhere in the FDS memory. But no single location is large enough to hold the section of code in its entirety,” NASA explains.

“So they devised a plan to divide the affected code into sections and store those sections in different places in the FDS. To make this plan work, they also needed to adjust those code sections to ensure, for example, that they all still function as a whole. Any references to the location of that code in other parts of the FDS memory needed to be updated as well.”

After this software update, and a then 22.5-hour wait to send instructions to Voyager, the team was able to communicate with it again and receive data from it. The mission is now expected to continue, albeit with occasional shutdowns of its instruments, until it finally powers down in the 2030s. From there, Voyager, and one of our oldest government computers, will still have a looooong journey ahead of it.

Source Link: The Oldest Government Computer Still Working Is Over 25 Billion Kilometers From Earth