The battery revolution would see humanity move away from burning fossil fuels in favor of electric power, but in order to get there, we need metal. A lot of metal. Vast crops of “deep sea potatoes” have been located in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone bursting with crucial battery ingredients, but what do we know so far about the pros and cons of deep-sea mining?

What is deep-sea mining?

At depths of around 4,000 meters (13,123 feet) below the sea, transporting manganese nodules from the seabed to the surface isn’t a simple task. The proposed method for collection involves deep-sea vehicles using water to dislodge the nodules – which aren’t attached to anything – and effectively scoop them up and send them to the surface via a pipe.

The key areas of concern center around what impact the plume created by the collectors might have, both when dislodging the nodules from the seabed, and that which gets dropped in the midwater when the nodules are transported to the surface. Sediment might not sound terribly dangerous, but there were concerns it might create dust storms that could travel long distances and choke small organisms.

“These particles could feasibly clog the feeding apparatus of these organisms for an area spanning hundreds of square kilometers from the point where the plumes generated,” said environmental manager for The Metals Company (TMC) Dr Michael Clarke, who after years working on environmental impact assessments for terrestrial mines has now moved to studying the impacts of mining the deep sea, speaking to IFLScience.

“What we’re actually finding when we go out there and do the tests is that the sediment goes into the vehicle and comes out the vehicle, forming what we call a turbidity flow. It behaves more like a liquid than a gas and doesn’t rise much more than 2 or 3 meters [6.6 to 9.8 feet] above the back of the collector. So, it doesn’t create the huge dispersive plumes that would be required for the sediment particles to travel hundreds of square kilometers and impact organisms over a huge area.”

The plume generated at the midwater could feasibly have had the same impact, but tests have shown it’s very dilute.

“You only have to get a few hundred meters away for it to dilute around 1,000 times and to become really hard to even find the sediment,” Clarke continued. “So, we really don’t think there’s much potential for these midwater sediment plumes to spread out over large areas either.”

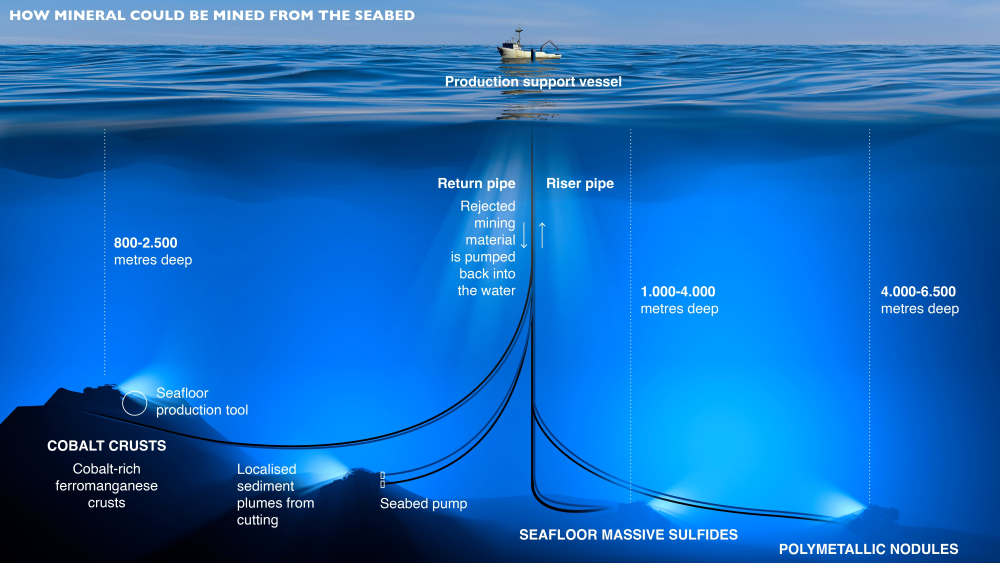

This stock diagram lays out the general jist of deep sea mining.

Image credit: Naeblys/Shutterstock.com

However, The Centre for Biological Diversity has stated that this “will inevitably harm” the sensitive ecosystems that exist across the marine environment, from sea-floor sponges and corals to turtles and sharks. As such, a group of 37 financial institutions has released a joint statement urging governments to not proceed with deep-sea mining until the risks are fully understood.

Deep sea mining vs. terrestrial mining

There’s no getting away from the fact that we don’t currently have enough metals in circulation for recycling to supply enough energy transition metals, given the amount we need for the green transition. These source metals need to come from somewhere, so we’re faced with the dilemma of working out which approach has the best yield-to-impact ratio.

“I’ve been implementing an environmental impact assessment like you would do for any mining project,” said Clarke. “The only difference is that this one is in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, a five-day sail from the nearest port at [a depth of] 4,000 meters.”

That depth is a crucial point in the pursuit of manganese nodules, because pitted against terrestrial mining sites there’s comparatively very little life in the benthos. TMC told IFLScience there are 13 grams [0.46 ounces] of biomass per square meter on the abyssal seafloor, whereas in the rainforests of Indonesia (one of the leading countries for metal mining) you’re looking at closer to 30 kilograms [66 pounds] of biomass per square meter.

Accessing metals from terrestrial sites means clearing forests, habitats, and ecosystems, making them vulnerable to erosion that can contribute to runoff, which ends up in the ocean. We know rainforests are biodiversity hotspots, and themselves act as a carbon sequestration tool, so while it’s important to establish the risks of deep-sea mining before we begin, there’s no getting away from the fact that existing methods are already incredibly damaging.

Do the pros outweigh the cons?

Academics across the globe have been researching life in the benthos to try and better understand this, hailing from institutions such as London’s Natural History Museum, the National Oceanographic Centre in Southampton, Heriot-Watt University in Scotland, the University of Leeds, the University of Bremen, the University of Hawaii, Texas A&M University, and the University of Maryland, among others.

What they’ve discovered is that while there is life on and around the nodules, including some larger animals, most of it is microscopic. Some of the earlier press directed at deep-sea mining has warned of the risk of mass extinction events, often using imagery of wildlife from shallower water to demonstrate potential victims, but given the already great cost of mining on land, it becomes a balancing act of where the greater harm lies.

The manganese nodules might not look like much, but there’s a lot of potential locked in these deep-sea potatoes.

Image credit: V.Gordeev/Shutterstock.com

“A lot of people have a real misconception of what the seabed looks like at 4,000 meters depth,” said Clarke. “There is life down there, there’s no doubt about it, but it’s not as abundant as is often portrayed.”

At present, 50 percent of the nickel market comes from Indonesia, where rainforest is flattened to make way for operations. This land is used by both humans and wildlife, so its absence is very apparent and its recovery is slow due to ongoing use. By comparison, after a collector has scooped up the nodules from the seabed, it can recover more quickly because little activity is going on here.

While these nodules do take millions of years to form, the argument that once it’s gone – it’s gone – is true of any source metal. On the other hand, only one option requires the ripping up of carbon-sequestering rainforest to reach it.

Carbon has been raised as a concern around deep-sea mining, as much of it is stored in sediments, but TMC explained that at present there’s no known mechanism through which this could rise to the surface. A 2020 study actually found that using nodules puts 94 percent less sequestered carbon at risk and reduces emissions by up to 80 percent depending on the specific metal.

“90 percent of the world’s exploration contracts for nodules are in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, which represent less than half of 1 percent of the global seafloor,” TMC PR and Media Manager Rory Usher told IFLScience.

“But this represents the largest source of manganese, nickel, and cobalt, anywhere on the planet and that dwarfs everything on land by many orders of magnitude. There are enough metals in situ at two of the sites that would satisfy the needs of 280 million cars, which represents every car in America, or a quarter of the world’s vehicle fleet.”

Research continues into the suitability of deep-sea mining for the task at hand, as well as the potential impacts it could have on the health of ecosystems, as well as humans – as some studies have found they may not be safe to handle due to radioactivity. They might only be the size of a potato, but there’s a lot of potential locked in those little nodules, we just need to work out if unleashing it is a good idea.

An earlier version of this article was published in May 2023.

Source Link: The Planet’s Largest Source Of Battery Metals Sits 4,000 Meters Beneath The Sea