Paleontologists are being forced to compete with rich collectors for access to dinosaur skeletons. When it comes to T. rexes in particular, the outcome is predictable, and science is suffering, a new study reveals.

Science has always had an awkward relationship with extreme wealth. For centuries, progress relied on those with enough inherited wealth to devote their time to scientific pursuits. Those fields that relied on extensive travel were even more strongly the preserve of the rich. Eventually, and particularly after World War II, governments recognized the value of investing in science, creating jobs based on skills, not family wealth. Rich philanthropists would sometimes swoop in and give some program a boost in return for having an institute or hospital named after them, but work continued regardless.

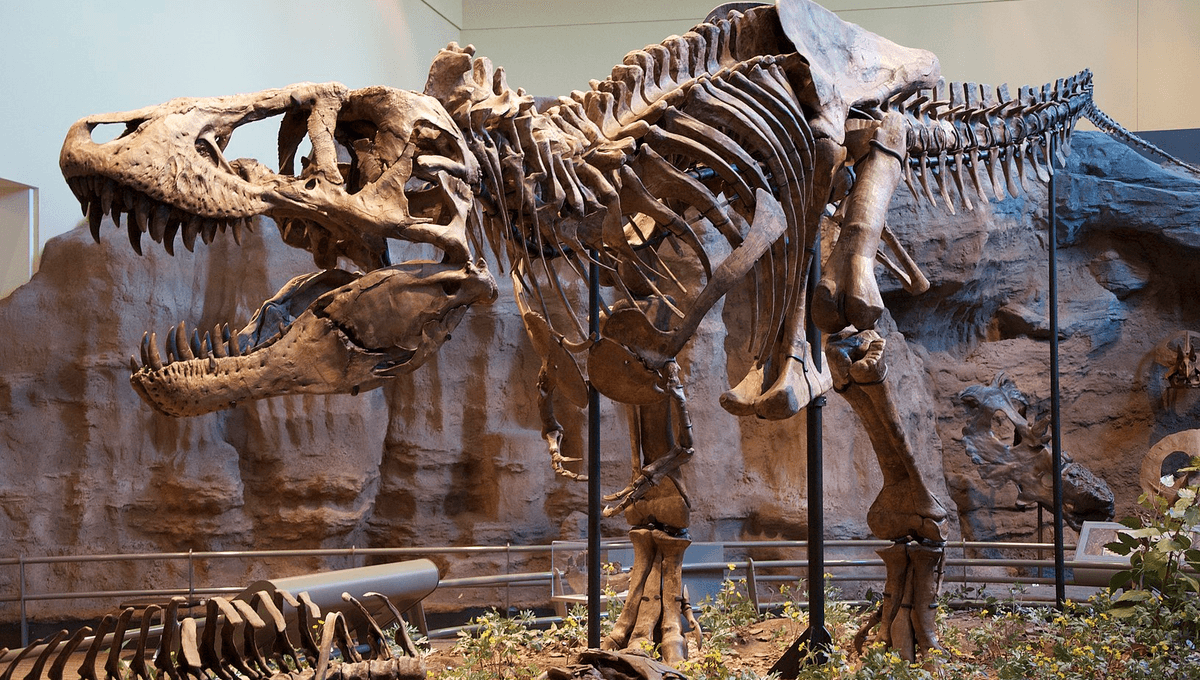

Just as that situation is coming into question in the United States, a study has been published highlighting an example of where the rich hinder science, rather than just failing to help. Wealthy collectors are snapping up prime dinosaur fossils and placing them where scientists can’t study them. The problem is so bad, the study is titled ‘Tyrannosaurus rex: An endangered species.’

When you are so rich you’ve run out of things to spend your money on, collecting something very rare is one thing you can do with it, rather than, say, give it to charity. Few things are rarer than relatively complete dinosaur specimens, particularly the largest and most famous species. Consequently, when someone digs up a dinosaur, they often have a choice of donating it to a museum, possibly getting a token price, or auctioning it off. It’s not hard to guess which is more popular.

Although this can be a problem for any dinosaur species, the study focuses on the most acute case: T. rexes. Apparently, the hyper-wealthy are particularly keen to have one of these in their living room.

Just because a skeleton is in a private collection does not mean it is necessarily lost to science entirely. “Apex”, the largest and most complete stegosaurus ever found and the most expensive fossil ever sold at auction, was snapped up by hedge-fund billionaire Ken Griffin last year for a record-breaking $44.6 million and now resides in the Kenneth C. Griffin Exploration Atrium of the American Museum of Natural History for scientists to study. The previous record-breaker, the mostly complete Stan the T. rex, was bought by a mystery buyer in 2020, prompting concern it may disappear from public view but was eventially revealed to be bought by the Natural History Musuem of Abi Dhabi with plans for both public viewing and a research facility to study such specimens.

Indeed, many collectors may consider it an additional feather in their cap if a paper is published describing what they own. The problem, Dr Thomas Carr of Carthage College notes in a new study, is that science depends on reproducibility. Researchers need to be able to check each other’s work for errors.

“Unfortunately, scientists regularly publish on privately owned T. rex fossils,” Carr writes. The rich owner who allows one person into their home to study their prize may be less inclined to let a lot of people scuff the carpet. That probably goes double if the first researcher has made a finding the owner likes. Those seeking to check the work may be excluded, and even the original research opportunity may only go to those good at sucking up to the owner.

Carr quantifies the problem, reporting, “There are 61 T. rex fossils in public trusts, whereas 71 are privately held.” He suspects the private number is larger, with many unrecorded. The problem is getting worse, with twice as many new T. rex discoveries being made by commercial companies as by museums. Those only interested in profits dominate locations where collectable fossils are common, like Montana and South Dakota.

You might think that 61 publicly held T rex fossils would be more than enough for research. After all, an expert in Denisovans or Homo floresiensiss would gnash their teeth in jealousy at the idea of having such a sample size. But there are things only specific fossils can teach us. “Of particular concern is the private ownership of juvenile and subadult specimens, the part of growth that is least understood,” Carr writes. Moreover, he notes that sometimes respectable sample sizes are essential, noting others’ conclusion: “A sample size of 70 to 100 specimens of adult non-avian dinosaurs are required to statistically detect sexual dimorphism,” even in a species where males and females average quite substantial differences. The figure would be much larger where the sexes are fairly similar in size.

Losing the opportunity to study fossils in private collections means failing to learn how the Cretaceous apex predator changed over time or adapted to different environments.

According to Carr, the way fossils are sold makes things worse, advertising them purely as decorative art, rather than emphasizing to buyers their potential for use in research. Much reporting reinforces the problem. As if that wasn’t enough of a problem, some collectors like to rename their fossils, leading to confusion over whether it’s the same one someone else has already studied. Even when this doesn’t occur, the context in which the fossils were found is almost always lost.

The Society of Vertebrate Paleontology has sometimes called on auction houses to restrict important sales to public institutions without success.

You can get a cheap T. rex for $1.55 million, but the most expensive sale was $38.68 million (inflation-adjusted), far beyond the budget of the average museum, even in better financial times.

Collectors argue that by raising the price of fossils, they spur discovery, including rescuing some that might otherwise be damaged. However, Carr argues that either these never get scientifically studied, or any reporting is done in a way that pollutes the literature rather than improving human understanding.

The study is open access on Palaeo-electronica.

Source Link: The Rich Love Tyrannosaur Fossils So Much That Scientists Are Missing Out