In the search for a vaccine that protects against a wide range of coronaviruses, the secret could be going sugar-free, one team has concluded. Progress has been reported at the American Chemical Society conference, while the team involved has also published two papers on how a related approach can improve the effectiveness of cancer vaccines.

ADVERTISEMENT

As new variants of COVID-19 appear, vaccine manufacturers struggle to keep up. Moreover, even when they produce a new vaccine tailored to fight against the latest variants, it’s a challenge to get people to take them. You don’t need to be a hardened anti-vaxxer to have let the time between boosters blow out – life often gets in the way.

A universal coronavirus vaccine would be ideal, but public health officials would settle for one that’s broad-spectrum, catching a wide variety of current and future forms that the virus evolves. Plenty of people have worked on the idea for the last five years, but Professor Chi-Huey Wong of the Scripps Research Institute favors an approach focused on sugar.

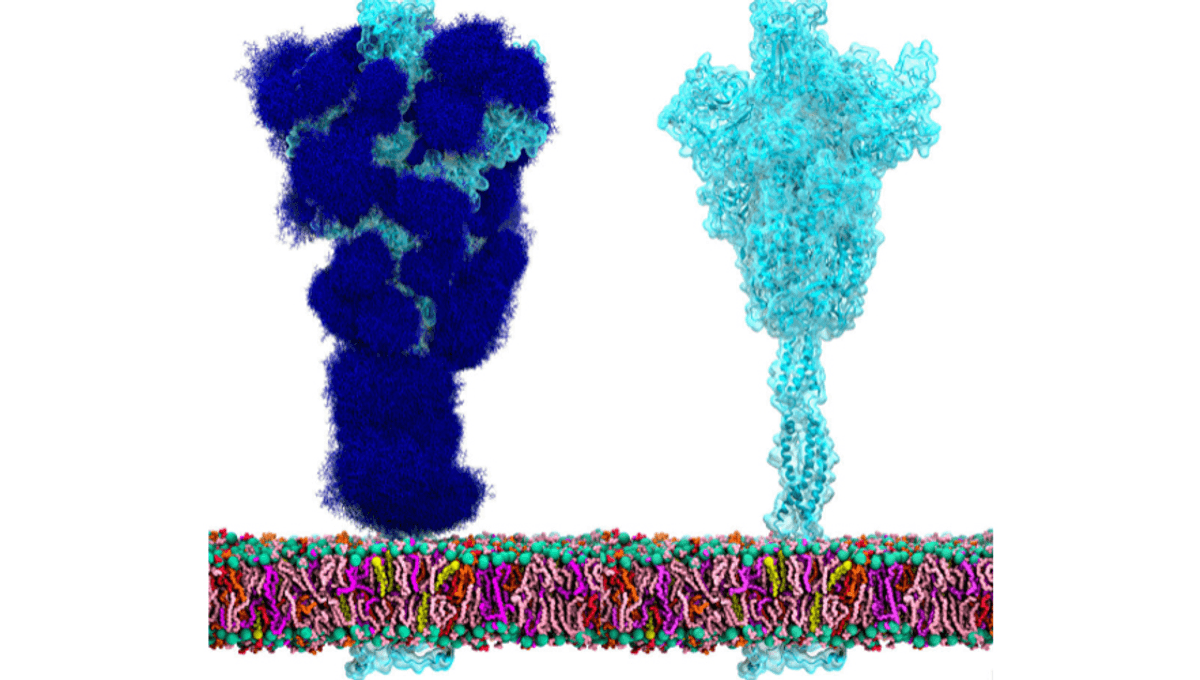

Viruses have evolved coatings of sugars to prevent agents of the immune system from locking onto their proteins. The solution, therefore, could lie in a virus that removes the sugars so that the immune system can do its job. Specifically, Wong wants a vaccine that removes the sugars around the spike protein that the virus uses to enter cells, as this is the area that mutates the most.

Rather than try to target the spike itself, as some others have, Wong’s team sought to expose the spike’s stalk by removing the sugar molecules, called glycans, that the virus wraps around itself. The vaccine trains the body to unleash enzymes that digest the sugars, and then target the exposed stalk region whenever it encounters a coronavirus.

In a talk delivered this week, Wong said the approach has proven successful in mice and hamsters, and discussed the progress of a Phase I clinical trial. The vaccinated animals produced more antibody diversity at higher concentrations than vaccines against individual coronaviruses.

“For a lot of vaccines, like smallpox and tetanus, we only have to be immunized once,” Wong said in a statement. “But we have to take a flu shot every year.” The hope is that one day, coronaviruses will be in the first category, not the second.

ADVERTISEMENT

To get there requires overcoming several obstacles, but success on some of these will have implications far beyond coronaviruses.

Some cancers also defend themselves with glycans on the surface of their cells. Wong’s team has published two papers, one on the enzyme these cancers use to produce the glycans, the other on targeting glycosphingolipids. Glycosphingolipids combine a glycan and a lipid into one molecule, and are expressed by certain cancers. The team claim to have achieved a tenfold improvement in the efficiency of reactions developed by others to make these defenses less effective, so that the cancer cells can be killed.

How anti-vaxxers who are also obsessively anti-sugar will feel about the work remains to be seen.

The targeting and enzyme papers are both published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society. Wong’s talk was delivered to the American Chemical Society’s Spring 2025 conference.

Source Link: The Secret To A Broad-Spectrum Coronavirus Vaccine Could Be Going Sugar-Free