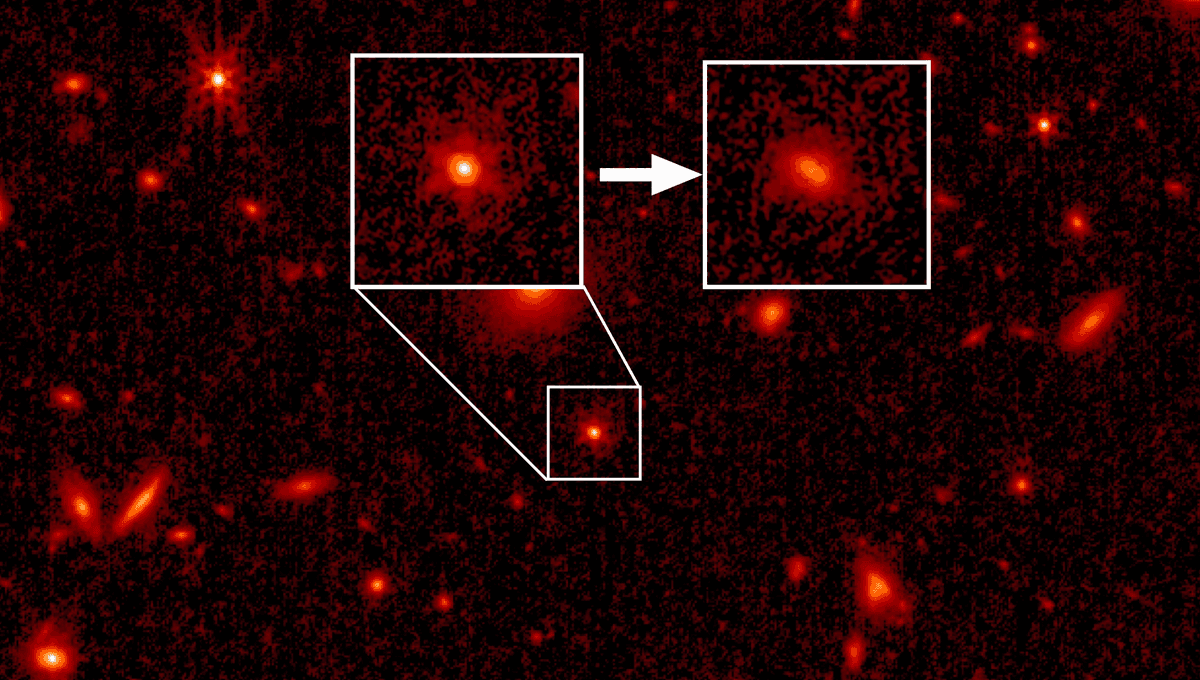

Quasars are the extremely active state of supermassive black holes. They are feeding at such a rate that their immediate environment becomes extremely luminous, so much so that they outshine their host galaxies. But those galaxies are still there, and it is very interesting to find out what they are up to. Now, astronomers have seen those galaxies for the furthest quasars yet.

The quasars in question are called J2236+0032 and J2255+0251. They are not the brightest of quasars from the early universe, and this is advantageous because it allowed researchers to use JWST to measure the surrounding galaxy starlight. Their light comes from when the universe was, respectively, 870 and 880 million years old.

“[Twenty-five] years ago, it was amazing to us that we were able to observe host galaxies from 3 billion years back, using large ground-based telescopes. The Hubble Space Telescope allowed us to probe the peak epoch of black hole growth 10 billion years ago. And now we have JWST available to see the galaxies in which the first supermassive black holes emerged,” co-author Dr Knud Jahnke, from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, said in a statement.

With that light, the team was able to estimate the stellar mass of the galaxies, which are 130 and 34 billion solar masses respectively. Their supermassive black holes weigh 1.4 billion and 200 million solar masses, respectively. The Milky Way has almost double the mass of the smaller quasar but a smaller supermassive black hole, called Sagittarius A*.

Despite the differences, the relation between the mass of stars and the mass of the supermassive black hole is in line with what we see in the local universe. This relation, known since the early 2000s, is a bit puzzling. We do not know if it exists because the stellar population and the supermassive black hole grow from the same processes such as galaxy mergers, or because they actually influence each other.

The fact that the relationship extends so early adds more to the puzzle. How did supermassive black holes get so big so quickly? Is there an even earlier time when this relationship was true? Or does it break when the universe was much younger?

The observations by JWST are the beginning of a more in-depth investigation into such distant sources. Ten more quasars are expected to be studied in such a manner and the team was also awarded time in the next observation cycle to study the host galaxy of J2236+0032 in much more detail.

The study is published in Nature.

Source Link: The Starlight Around An Early-Universe Quasar Seen For First Time