In 1882, in a workhouse in Leicester, England, a young man named Joe Merrick was having an operation on his face. He had been born 20 years earlier, apparently a perfectly normal, healthy baby – but now, he was so covered in deformities and protrusions that he could barely eat or speak.

In years to come, the mass the surgeons removed from Merrick’s face that day would be referred to as his “trunk” – and Merrick himself would go down in history with a matching pseudonym: The Elephant Man.

Who was Joseph Merrick?

Joseph Carey Merrick was born in a slum in 1862, and things pretty much went downhill from there. Within two years, he had started to develop swellings around his mouth, and over the course of a few months, these growths spread up across the young child’s cheeks and forehead.

By age five, Merrick had started showing other, equally strange symptoms. His skin became loose and rough: “thick [and] lumpy,” he would later write in his Autobiography of Joseph Carey Merrick, “like that of an elephant, and almost the same colour.”

His physical deformities continued to grow, and it was around this age that he took a hard fall, damaging his left hip. The injury became infected, leaving Merrick permanently disabled as well as disfigured. Aged eight, his younger brother died, and three years after that, his mother followed. Her death was, Merrick would later write, “the greatest misfortune of [his] life.”

“He [would] always… carry her in his mind as an idealized but vivid memory,” wrote Michael Howell and Peter Ford in their 2001 biography, The True History of the Elephant Man. “The memory was of someone who had seemed the source of all the warmth and comfort he ever knew.”

Without his mother, his life quickly became – in his own words – “a perfect misery”. His father remarried soon after, and neither parent showed the child much in the way of affection: he would later recall being “taunted and sneered at” so severely by his stepmother that he “would not go home to my meals, and used to stay in the streets with a hungry belly rather than return for anything to eat.”

By the age of 13, Merrick had left school and taken a job in a cigar factory, but as his condition worsened, he no longer had the manual dexterity needed for the job. He got a job selling haberdashery door-to-door, but his deformities made him difficult to understand, and potential customers were put off by his appearance.

At 15, after a day of particularly poor sales, his father beat him so severely that he left home for good. He was now homeless, and soon afterward he had his sales license revoked – the local authorities considered his appearance a public nuisance – and in 1879, he was admitted into the Leicester Union Workhouse.

He would stay in the workhouse for four years, which as anybody familiar with Oliver Twist can tell you, is about four years longer than ideal. It was, by design, more akin to a prison than a charitable organization. Designated a member of group one, Merrick was – somewhat inexplicably, since he had ended up there because he was too disabled to support himself – considered fit to work, and so his days would have been spent adhering to strict rules, and performing dull and menial jobs like breaking stones or pulling rope apart.

Eventually, though, he figured out a way to escape. In a quintessentially Victorian career move, he decided to join a traveling “Freak Show”.

“Since the day when he could toddle no one had been kind to him,” wrote Frederick Treves, a London surgeon who happened to see Merrick on display one day in late 1884.

“[His] life up to the time that I met him… was one dull record of degradation and squalor,” he recorded in his memoir The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences. “He was dragged from town to town and from fair to fair as if he were a strange beast in a cage. A dozen times a day he would have to expose his nakedness and his piteous deformities before a gaping crowd who greeted him with such mutterings as ‘Oh! what a horror! What a beast!’… His sole idea of happiness was to creep into the dark and hide.”

Despite this being the part of his life that made him famous – this was when he was first marketed as the Elephant Man, advertised as “Half-a-Man and Half-an-Elephant” – it was actually the shortest era of his life, lasting only a year or two.

Eventually, with the help of Treves, Merrick found himself in the London Hospital, where he stayed until his death in 1890. In his obituary, he was remembered as “quiet and unassuming, very grateful for all that was done for him, and [somebody who] conformed himself readily to the restrictions which were necessary.”

What was Joseph Merrick’s medical condition?

It might seem strange, given how much detail we have from his lifetime, but we don’t actually know for sure what caused Joseph Merrick’s deformities.

“Various conditions have been suggested as the cause of Merrick’s disability and appearance,” explained Kate Jarman, a trust archivist at Barts Health NHS Trust, which now owns the Royal London Hospital.

The two main culprits have historically been Proteus syndrome and neurofibromatosis, she told IFLScience, “but the diagnosis remains unknown.”

The earliest explanation for Joseph Merrick’s changing appearance was one that, today, seems almost Medieval in its reasoning: it was because his mother was kicked by an elephant while she was pregnant.

“The deformity which I am now exhibiting was cause by my mother being frightened by an Elephant,” Merrick wrote in his autobiography. “My mother was going along the street when a procession of Animals were passing by…and unfortunately she was pushed under the Elephant’s feet, which frightened her very much; this occurring during the time of pregnancy was the cause of my deformity.”

Merrick would not have been alone in this assumption – in fact, he most likely heard it from his mother in the first place. The concept of “maternal impression” – that traumatic physical or mental experiences during pregnancy could affect a growing fetus – was popular among both the public and medical professionals at the time. A woman who had been hurt by an elephant giving birth to a child growing huge, trunk-like deformities and loose grey skin would completely make sense under this worldview.

Of course, today this idea seems absurd. Yes, maternal trauma during pregnancy can produce changes in the developing baby, but it’s nowhere near as simple as “kicked by elephant = baby will look like elephant”.

It wasn’t until Merrick was noticed by Treves that any medical specialists took a serious look at him – and even then, precious few seemed all that interested in him as a diagnostic case. This is, however, the period where we start getting clinical descriptions of his condition: he had “an extraordinary appearance, owing to a series of deformities,” read the December 1884 digest of the British Pathological Society, published in the British Medical Journal shortly after the meeting at which Merrick had been exhibited.

There were “some congenital exostoses of the skull; extensive papillomatous growths and large pendulous masses in connection with the skin; great enlargement of the right upper limb, involving all the bones,” the author recorded. “From the massive distortion of the head, and the extensive areas covered by papillomatous growth, the patient had been called ‘the elephant-man’.”

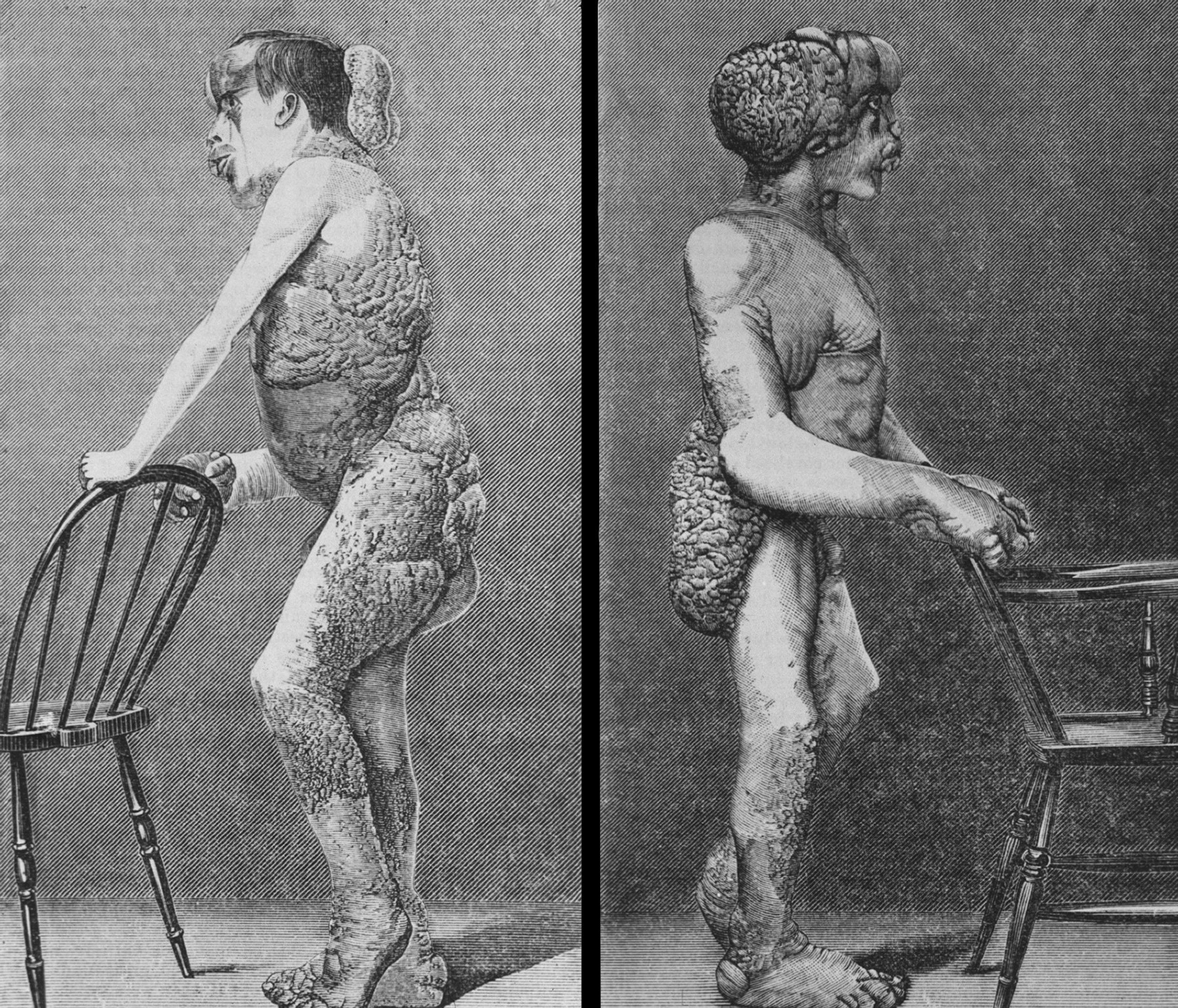

These standing profile engravings of Merrick were published in the British Medical Journal in 1886. Image credit: Everett Collection/Shutterstock.com

Treves himself made some more particular records. It’s because of him that we know Merrick’s head was 91 centimeters (36 inches) in circumference – more than 50 percent larger than the average of the time – while his right wrist and fingers measured 30 centimeters (12 inches) and 13 centimeters (5 inches) in circumference respectively.

His bones were deformed in both legs, his right arm, and his skull – but it was the skin abnormalities that likely caused most interference in Merrick’s life: there were areas where his subcutaneous tissue had grown so large, and so heavy, that his skin hung down almost like curtains in places. The worst of these was on Merrick’s buttocks, Treves noted, here, the skin fold hung down to the middle of his thigh and was so large and awkward that it interfered with his ability to use the bathroom.

On top of that, his skin was covered in warty growths – some as small as pimples; others huge, the shape and texture of a cauliflower. The worst part of all was the smell: an inescapable odor that emanated from the growths and followed Merrick wherever he went.

But despite all this – and although Merrick’s facial deformities meant that his speech was still barely intelligible – he was, in general, pretty healthy. His left arm and hand were normal; he was physically strong and mentally sharp. So what was it that made him look so distinctive?

“[His] obscure condition… puzzled his contemporaries, and fascinates clinicians to this day,” wrote Barts Trust orthopedists Catherine Huntley, Angus Hodder, and Manoj Ramachandran in their 2014 paper titled Clinical and historical aspects of the Elephant Man: Exploring the facts and the myths.

“Throughout the 1900s, a number of theories were advanced to explain the numerous growths that covered his body: neurofibromatosis, Proteus syndrome, and a combination of childhood injury, fibrous dysplasia, and pyarthrosis,” they explained. “The debate continued throughout the 20th century without resolution.”

The first popular modern suggestion for Merrick’s condition was a disease called neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) – a genetic condition that causes benign tumors to grow along the nerves. It mostly affects the skin, causing birthmarks known as “café au lait spots” and clusters of freckles in places like the armpits and groin, but it can also create problems with the bones, eyes, and nervous system.

There are definitely similarities, visually, between Merrick and the most extreme presentations of NF1. But the most important symptoms – the café au lait spots, for example, and neural tumors – were never observed in Merrick’s case.

A more likely diagnosis, therefore, was Proteus syndrome, American pathologists Michael Cohen and John Tibbles suggested in 1986. This is a randomly-occurring and extremely rare genetic condition – it affects less than one in a million worldwide – but it’s a better fit for Merrick than NF1. It explains why his symptoms were “[so] much more bizarre than those commonly seen in neurofibromatosis,” Cohen and Tibbles wrote, noting that “Merrick… had the following features compatible with this diagnosis: macrocephaly; hyperostosis of the skull; hypertrophy of long bones; and thickened skin and subcutaneous tissues, particularly of the hands and feet, including plantar hyperplasia, lipomas, and other unspecified subcutaneous masses.”

Today, the general consensus is that Merrick’s condition was indeed Proteus syndrome – although the idea that he had NF1, unfortunately, refuses to die completely. The only way to prove it one way or the other, though, would be via genetic testing, and all attempts to do so have so far proved inconclusive.

How was Joseph Merrick treated in his own lifetime?

Merrick lived his whole life in Victorian England, and while there are many adjectives you can use to describe that time and place, “kind” and “respectful” are not the first that usually spring to mind. Merrick was a professional “freak”: rather than receiving medical treatment or basic compassion, he was put on display for strangers to come and ogle at in a dark room.

In fact, Merrick, especially at what might be called the height of his fame, didn’t really go outside at all. He “could not show himself in the streets. He would have been mobbed by the crowd and seized by the police,” Treves recalled. “He was, in fact, as secluded from the world as the Man with the Iron Mask.”

When he had to travel, he took a cab in disguise: a floor-length black cloak, a pair of “bag-like slippers” on his feet, and on his head, Treves wrote, “a cap of a kind that never before was seen. It was black like the cloak, had a wide peak, and the general outline of a yachting cap… From the attachment of the peak a grey flannel curtain hung in front of the face. In this mask was cut a wide horizontal slit through which the wearer could look out.”

It wasn’t until he entered the London Hospital that Merrick received much kindness at all. Even then, it took a lot of luck – and a full-scale Victorian PR campaign – to get things rolling.

“Merrick received no active medical treatment in his own lifetime, but he was admitted to the London Hospital as a resident, rather than a patient, in 1886… by which time he was impaired from living a ‘normal’ life by his deformities,” Jarman told IFLScience.

But there was a problem: the hospital had no permanent rooms at the time. Treves’s boss, Francis Carr Gomm, was forced to appeal to the public for help supporting Merrick, who by this point Treves was convinced had little time left to live in any case.

“Treves instigated a fundraising campaign to support his accommodation,” Jarman explained, “and rooms were allocated to Merrick in the East Wing of the hospital… on a long-term basis.”

Living at the hospital evidently agreed with Merrick. His Victorian doctors weren’t able to administer the wide range of treatments for Proteus syndrome we employ today – and in fact, it would be nearly a century before the condition even got a name, let alone a treatment protocol – but they could bathe him daily, and engage him in conversation.

“With the use of the bath the unpleasant odor to which I have referred ceased to be noticeable,” wrote Treves. “I very soon learnt his speech so that I could talk freely with him. This afforded him great satisfaction, for, curiously enough, he had a passion for conversation, yet all his life had had no one to talk to.”

Slowly but surely, the “Elephant Man” who had so recently been a sideshow in a Whitechapel penny gaff, became a bona fide celebrity – but this time, it was among a much more refined crowd. “The Merrick whom I had found shivering behind a rag of a curtain in an empty shop was now conversant with duchesses and countesses and other ladies of high degree,” Treves recalled. “They brought him presents, made his room bright with ornaments and pictures, and, what pleased him more than all, supplied him with books.”

When and how did Joseph Merrick die?

Treves’s intuition that Merrick was not long for the world did indeed prove accurate – although it wasn’t, as he had originally suspected, a heart condition that eventually led to his death.

“Merrick’s condition gradually deteriorated during his four years at the London Hospital,” Jarman told IFLScience.

“He died on 11 April 1890, at the age of 27 due to accidental suffocation,” she said. “[It was] probably caused by pressure due to his deformities.”

An autopsy carried out by Treves found that Merrick had died with a dislocated neck, which had most likely severed the arteries in his vertebrae. Knowing his friend as he did, he concluded that Merrick must have tried to sleep lying down – something that his large head had always made impossible – and his neck had snapped by the sheer weight of his skull.

“The [position] he was compelled to assume when he slept was very strange. He sat up in bed with his back supported by pillows, his knees were drawn up, and his arms clasped round his legs, while his head rested on the points of his bent knees,” Treves wrote.

“He often said to me that he wished he could lie down to sleep ‘like other people.’ I think on this last night he must, with some determination, have made the experiment,” he concluded. “The pillow was soft, and the head, when placed on it, must have fallen backwards and caused a dislocation of the neck. Thus it came about that his death was due to the desire that had dominated his life – the pathetic but hopeless desire to be ‘like other people.’”

What happened to Joseph Merrick’s body after he died?

By the time Joseph Merrick died, popular opinion had turned against exhibiting human beings in freak shows – at least, in shows that labeled themselves as such, since Merrick had still commanded quite a regular audience in his rooms at the London Hospital.

Once shuffled off the mortal coil, though, it was open season. Despite being a devout Christian, Merrick never got a proper burial; instead, his skeleton was separated from his soft tissues and mounted for medical students to examine.

While his tissue remains were eventually rediscovered back in 2019, his skeleton remains with the hospital, Jarman told IFLScience – albeit no longer on display. “The skeleton of Joseph Merrick is held in a private part of the pathology museums within the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London (a successor to the London Hospital Medical College),” she confirmed.

“A resin cast of the skeleton was displayed in the former Royal London Hospital Museum between 2011 and 2020,” she added, “but this was on loan from the medical school also, and has been returned since the closure of the museum.”

Today, more than a century after his death, The Elephant Man still holds a place in our cultural vocabulary. He’s been the subject of countless books, plays, and films, and is, without doubt, more famous now than ever before. And perhaps the most ironic part of it all is that, had you asked Merrick himself, he might have said his deformities were the least interesting part of him of all. After all, as he signed off in his correspondences:

If I could reach from pole to pole

Or grasp the ocean with a span,

I would be measured by the soul;

The mind’s the standard of the man.

Source Link: The Surprising, Sad, And True Story Behind "The Elephant Man"