Physicists have finally observed a phenomenon whose predecessor was observed in the mid-19th Century. The scientists who made it happen claim the work may lead to better management of temperatures where this needs to be precise and highly localized.

William Thomson (better known as Lord Kelvin) noted in 1851 that if one end of an electrical conductor is warmer than other, and a current flows through it, heat is absorbed or released. Whether you get more heat or less depends on whether the current is going with or against the temperature gradient. This was one of three related thermoelectric effects discovered in the 19th Century connecting the behavior of heat and electricity. It’s been observed in metals including copper, zinc and silver. The change in temperature is determined by the material’s Thomson Coefficient, as well as the gradient and the strength of the current.

A negative Thomson effect has also been observed in metals including iron, where the change in temperature acts in the opposite direction, relative to current flow. Physicists have theorized that under the right circumstances there should be a transverse Thomson effect, one that happens at right angles to the flow of current. Now it has been observed for the first time.

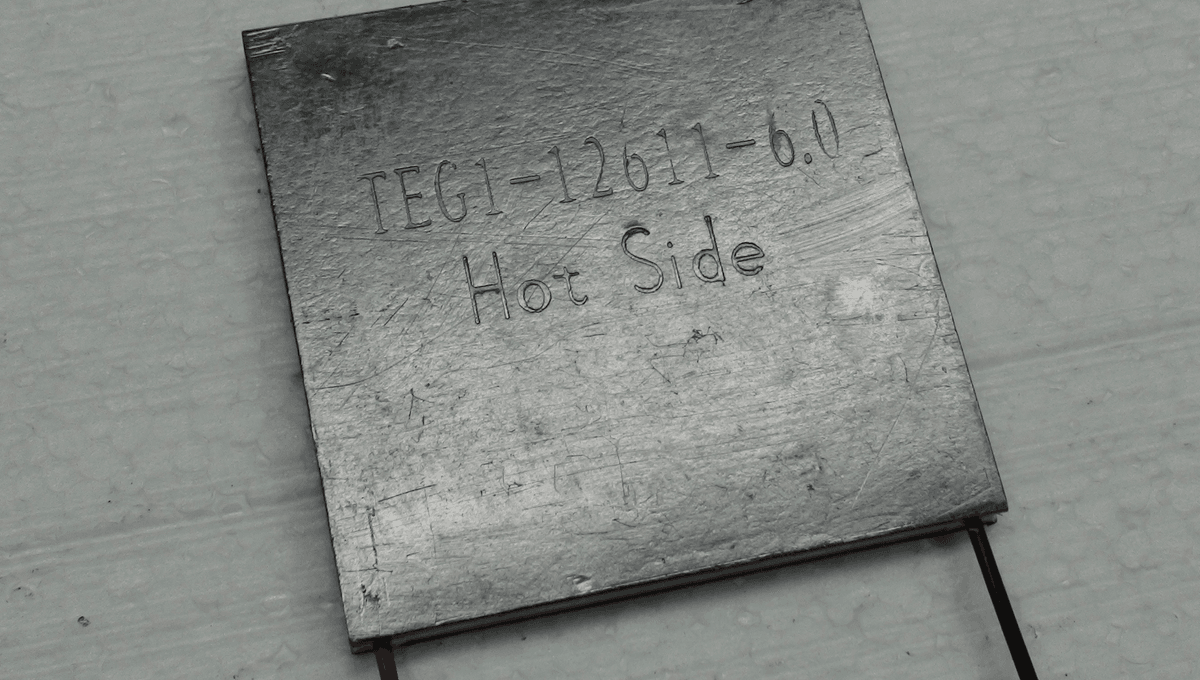

To produce the Transverse Thomson effect, researchers at two Japanese Institutes used a semimetal conductor made of bismuth and antimony, which goes some way to explain why it hasn’t been spotted before. They then applied a current, temperature gradient and magnetic field at right angles to each other. If you’re having trouble visualizing that, imagine a sheet of Bi88Sb12 where the current flows lengthways, heat is applied to one side (not end) and the magnetic field direction is from above.

The team demonstrated that not only can they heat or cool the sheet, but they can reverse the changes by flipping the magnetic field direction. Looking at changes within the sheet, the authors found differing responses around the edges, but temperatures rose or fell evenly throughout most of the material. The edge behavior was attributed to the Ettingshausen effect, which occurs whether there is a temperature gradient or not, being stronger than the Transverse Thomson there.

The authors estimate the Transverse Thomson Effect is about 15 percent as strong as the one effect Thomson actually discovered, but this may be increased in other materials.

The Thomson Effect occurs because electrons are more closely packed in cool parts of a material than warmer areas, and the movement between creates or releases potential energy.

Just to be clear, the Thomson Effect described here is different from the better-known Joule-Thomson Effect, which Thomson co-discovered around the same time and relates to gases, not solids.

The study is published in Nature Physics.

H/T Phys.org

Source Link: The Transverse Thomson Effect Finally Observed After 174 Years