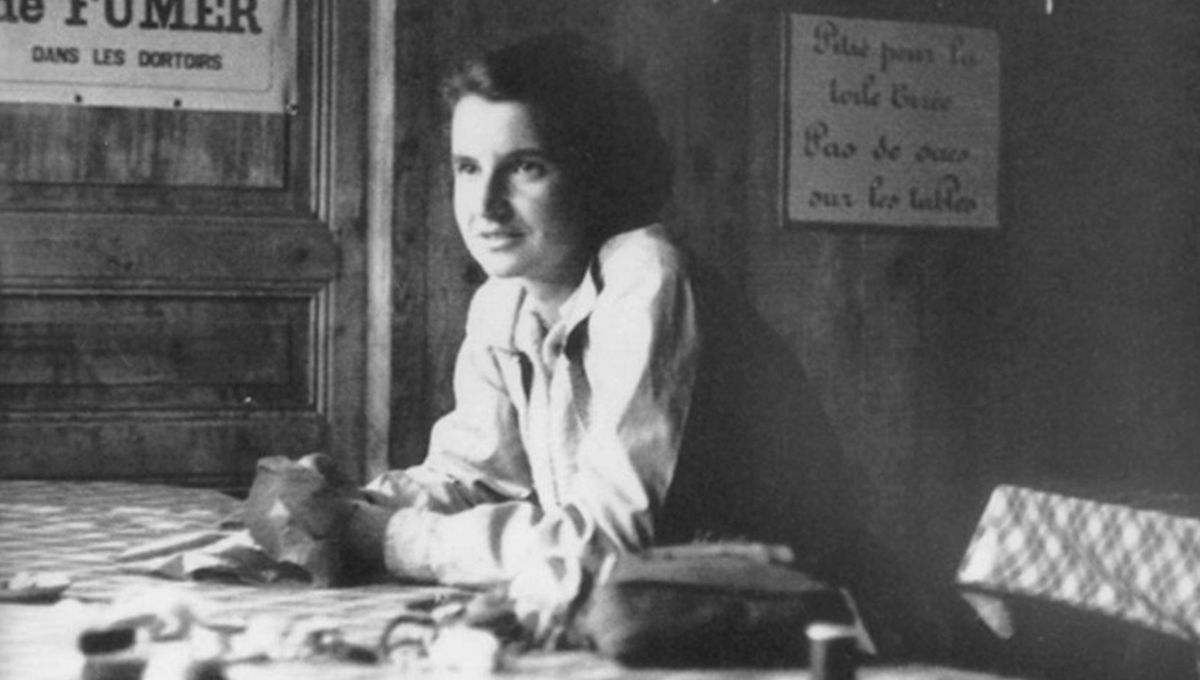

The story of Watson and Crick, and the discovery of the double-helix structure of DNA, has become the stuff of scientific legend in the 70 years since their seminal paper detailing the result – and it’s probably not for the reasons they would have hoped. Despite the undeniable importance of the discovery, it’s today more likely remembered as a tale of misogyny and betrayal – one in which Crick and Watson stole the results of their female coworker, Rosalind Franklin, and took the fame and recognition that should, by rights, have been hers, for themselves.

This narrative, however, does Franklin an injustice, argue Matthew Cobb and Nathaniel Comfort in a new Comment piece for Nature. While there’s no question that Franklin’s life and career were marked by the sexism of her day, “getting [her] story right is crucial,” the pair argue – not least because of the status she now enjoys as a groundbreaking woman in science.

The History of Rosalind Franklin

The tale of Franklin, and her role in the discovery of the structure of DNA, is one that has seen a few transformations over the years. At first, of course, her contributions were presented as almost incidental: her data was used by Watson and Crick without permission and, initially at least, practically any public recognition. When the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded for the discovery in 1962, she once again went unnamed: it was Watson, Crick, and Maurice Wilkins who received the award, rather than Franklin, due to her tragically early death a few years earlier.

But less than a decade later, as second-wave feminism started to gain movement, the story changed radically – and it was, in a large part, thanks to a newly published memoir from Watson himself.

“Rosy, as we called her from a distance […] would not think of herself as Maurice’s assistant,” Watson recalled in The Double Helix, his 1968 memoir about the discovery – using the nickname for Franklin that he knew she hated, yet he insisted on.

“By choice she did not emphasize her feminine qualities,” he complained. “She was not unattractive and might have been quite stunning had she taken even a mild interest in clothes. This she did not… Clearly Rosy had to go or be put in her place.”

“The thought could not be avoided,” he concluded, “that the best home for a feminist was in another person’s lab.”

Combined with Watson’s portrayal of Photo 51 as the eureka moment of the discovery, Franklin’s reputation was transformed. Suddenly, she was not a passive participant in the discovery of the structure of DNA, but a maligned feminist icon, whose work and proper recognition had been stolen out of disdain for her gender.

“The reality is, is that, if life was fair, which it’s not, it would be called the Watson-Crick-Franklin model,” Howard Markel, director of the Center for the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan and author of The Secret Life: Rosalind Franklin, James Watson, Francis Crick, and the Discovery of DNA’s Double Helix, told PBS in 2021.

Without Frankin’s data, he said, Crick and Watson “absolutely would not” have figured out the structure of DNA. “It would have been very hard for them,” he explained – though the pair themselves believed that “Rosalind would have figured it out in a few weeks.”

Despite this – or perhaps because of it – there followed a “very extensive campaign” to cover up just how fundamental Franklin’s contribution to the discovery truly was, the story goes. “I think [Crick and Watson] never thought of Rosalind as a serious competitor of their level,” Markel said. “[It] was chauvinism to the nth degree.”

But according to Cobb, professor of zoology at the University of Manchester, and Comfort, a professor of history of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, it’s high time that this narrative, too, got a revamp. As revealing as Watson’s account was, they argue, it still paints Franklin in an unrealistic light – both in terms of her ability, and how much recognition she might have received in her own lifetime.

“Because of Watson’s narrative, people have made a fetish of Photograph 51. It has become the emblem of both Franklin’s achievement and her mistreatment,” they write in their new Comment piece.

“But Watson’s narrative contains an absurd presumption. It implies that Franklin, the skilled chemist, could not understand her own data, whereas he, a crystallographic novice, apprehended it immediately.”

What we get wrong about Franklin’s story

Far from being the unsung heroine of the discovery, new evidence found by Cobb and Comfort at Franklin’s archive at Churchill College in Cambridge, UK, suggests that Franklin came tantalizingly close to enjoying the same level of fame as Watson, Crick, and Wilkins.

Mere weeks after the publication of those landmark papers that first described the structure of DNA, a journalist named Joan Bruce picked up the story for Time magazine, Cobb and Comfort discovered – and had it ever gone to print, the traditional story of who was responsible for the discovery may have been very different.

“Although Bruce’s article has never been published – or described by historians, until now – it is notable for its novel take on the discovery of the double helix,” the pair write.

“Bruce portrayed the work as being done by ‘two teams’: one, consisting of Wilkins and Franklin, gathering experimental evidence using X-ray analysis; ‘the other’ comprising Watson and Crick, working on theory,” they explain. “To a certain extent, wrote Bruce, the teams worked independently, although ‘they linked up, confirming each other’s work from time to time, or wrestling over a common problem’.”

Franklin was presented throughout as “every bit a peer” of her male coworkers, Cobb and Comfort write; “from the outset… represented as an equal member of a quartet who solved the double helix.” Yet the article never made it to print – thanks, unfortunately, to the complexity of the discovery itself.

“Bruce was not so strong on the science,” Cobb and Comfort explain, “perhaps because Franklin told Bruce that it needed an awful lot of work to get the science straight”

Eventually, the piece was buried, leaving only the draft copy in the Churchill College archives for Cobb and Comfort to find some 70 years later.

Combined with a previously overlooked letter from one of Franklin’s colleagues to Crick – one which implies she knew exactly what she was looking at when she saw the crystalline structures of DNA – it’s clear that Franklin’s reputation is now due an upgrade, the pair argue.

“Franklin did not fail to grasp the structure of DNA. She was an equal contributor to solving it,” they write.

“She deserves to be remembered not as the victim of the double helix, but as an equal contributor to the solution of the structure.”

Source Link: The True Story Of Rosalind Franklin Is More Complicated Than You Think