The Winchcombe meteorite has been analyzed in a level of detail previously reserved for space mission retrievals, rather than rocks that fall of their own accord. The result is an insight into its history that shows it had survived multiple rounds of being smashed apart before reforming, as well as processing by water, before it hit the atmosphere.

Its diminutive size means Britain doesn’t get a lot of meteorites, and those that do land are quickly covered by vegetation. Consequently, when a stone fell over Winchcombe in 2021 – and most pieces were recovered within 12 hours – it was a cause of celebration.

The excitement went global when it became clear the Winchcombe meteorite is a carbonaceous chondrite, a category of meteorites that are thought to offer the most direct window into the origins of the Solar System. Equally importantly, a few carbonaceous chondrites have been found to contain building blocks of life, reshaping our thinking on our origins.

Previous work by some of the same authors revealed the Winchcombe meteorite was once part of the regolith (broken rocks and dust) near the surface of a substantial asteroid.

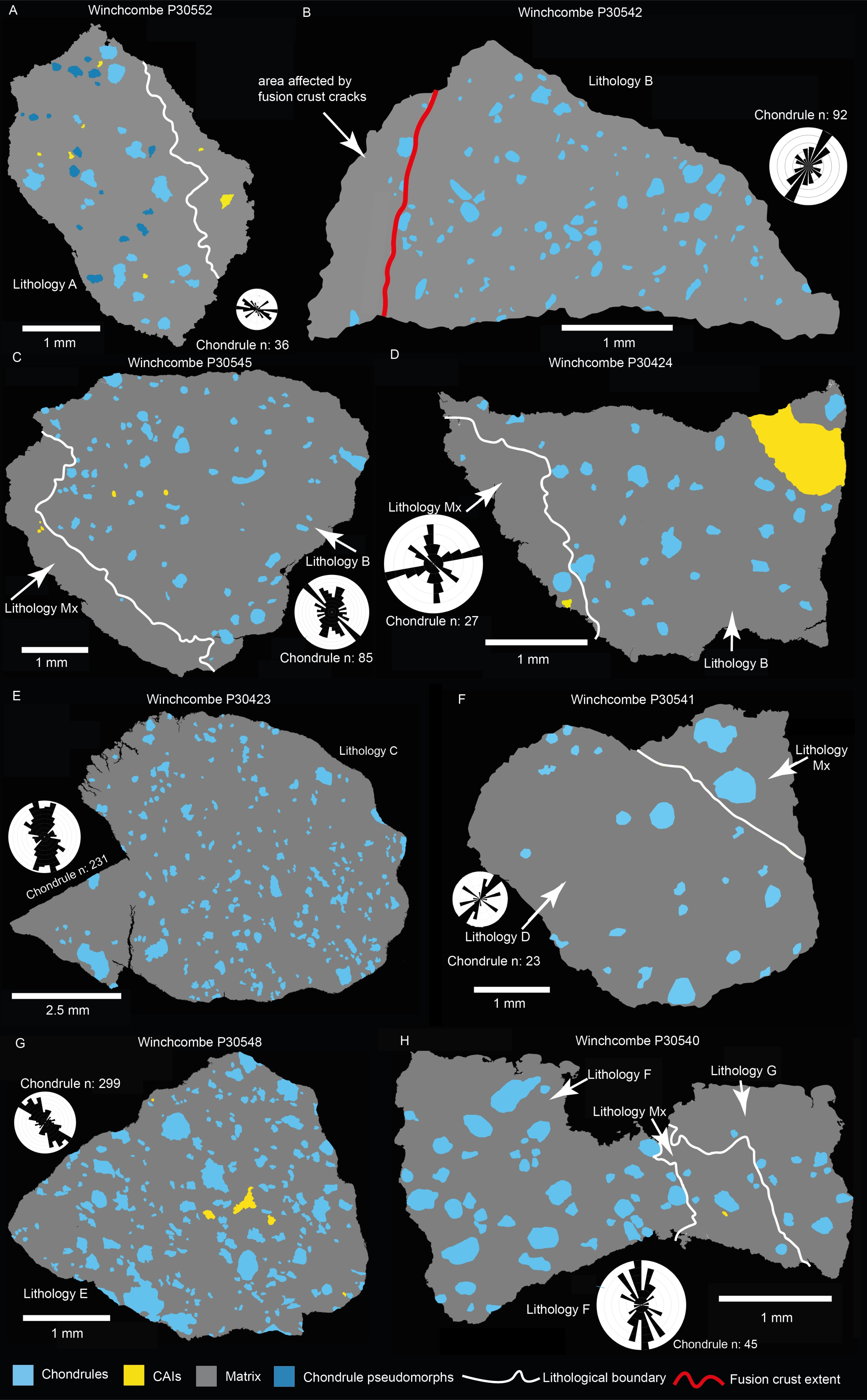

Unlike most meteorites, carbonaceous chondrites have escaped exposure to high temperatures, preserving their original materials. However, in the Winchcombe case, that doesn’t mean we’re seeing it much as it was 4.5 billion years ago. Like most meteorites, Winchcombe is made of breccia, pieces of rocks forced together under pressure to form new rock. What is remarkable in this case is that eight types of carbonaceous chondrites went into making this one meteorite.

“If you imagine the Winchcombe meteorite as a jigsaw, what we saw in the analysis was as if each of the jigsaw pieces themselves had also been cut into smaller pieces, and then jumbled in a bag filled with fragments of seven other jigsaws,” said Dr Luke Daly of the University of Glasgow in a statement.

Each type of constituent meteorite had been exposed to, and changed by, water. Moreover, the water made changes inside these constituents, not just at the surface. Tiny grains whose chemistry has been water-altered sit next to grains that have not. Although breccia containing materials showing different alteration processes is common for carbonaceous chondrite meteorites, Winchcombe takes it to extremes: grains hundreds or thousands of times smaller than a human hair with very different water influence are juxtaposed.

This challenges the previous expectation that aqueous processing happened relatively early in the lives of the asteroids from which carbonaceous chondrites come, and brecciation occurred later.

To create this confusing mixture, the scientists who examined the Winchcombe meteorite concluded it must have gone through a repeated process of being part of collisions that broke it (and the larger asteroid it was part of) apart, before they reassembled under gravity, all while far enough from the Sun to hold onto its water.

The shapes and alignments of pieces of the eight different types of rocks are crucial to reconstructing the meteorite’s history.

That’s not the end of Winchcombe’s weirdness: Its composition indicates it originally contained a large amount of frozen carbon dioxide. Some of the carbon survives in the form of minerals familiar from Earth; like aragonite, which forms in the early stages of alteration by water on meteorites; and calcite and dolomite, which require more extensive liquid processing.

Other minerals have led researchers to suspect the rock once contained more carbonate early on, now replaced by other minerals. The process of dry ice melting that could have caused this may also be responsible for the carbonate veins OSIRIS-REx saw on Bennu. The authors raise the possibility carbonaceous chondrites in general may have started out with more carbonate than has been thought.

Fine-grained minerals from the Winchcombe meteorite, showing the diversity of minerals and with elements shown

In unjumbling the meta-jigsaw, Daly said the team has learned how exposure to water shaped the rock prior to it hitting the Earth’s atmosphere.

“This level of analysis of the Winchcombe meteorite is virtually unprecedented for materials that weren’t directly returned to Earth from space missions, like Moon rocks from the Apollo programme or samples from the Ryugu asteroid collected by the Hayabusa 2 probe,” said co-author Dr Leon Hicks of the University of Leicester.

The excitement the scientists felt was expressed by Dr Diane Johnson of Cranfield University, who said “Research like this helps us understand the earliest part [of] the formation of our Solar System in a way that just isn’t possible without detailed analysis of materials that were right there in space as it happened. The Winchcombe meteorite is a remarkable piece of space history and I’m pleased to have been part of the team that has helped tell this new story.”

The study is published open access in the journal Meteoritics and Planetary Science.

Source Link: The Winchcombe Meteorite Had A Wet And Wild Journey To Earth