A colossal aspen stand in Utah that holds the distinction of being the world’s largest living thing appears to be fragmenting as a result of overgrazing. Known as Pando, the enormous organism is predominantly preyed upon by mule deer and cattle, and new research indicates that human efforts to protect the stand may be exacerbating the problem.

Covering 106 acres and with a dry weight mass of around 6,000 tonnes (13 million pounds), Pando is easily mistaken for a sprawling forest consisting of more than 40,000 individual trees. In fact, it’s a group of genetically identical stems with a shared root system, and therefore constitutes a single organism.

Though the exact age of this collection of clones is unknown, scientists believe that Pando probably dates back to the end of the last Ice Age. As a keystone species, the aspen stand provides the foundation for an entire ecosystem and supports hundreds of other species.

However, research conducted in 2017 revealed that browsing deer and cattle were eating too many young aspen shoots and preventing them from reaching maturity. This meant that as older trees died out, they were no longer being replaced by new growth, threatening the continuation of this magnificent life form.

In response, managers erected fences around Pando, hoping to keep grazing animals at bay. However, a new study that evaluates the success of this strategy finds that the fences may be having a negative impact.

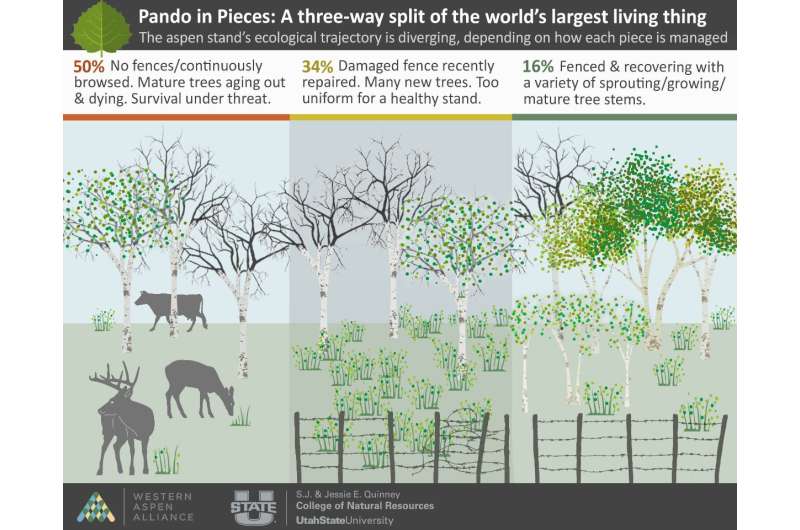

According to the new research, only 16 percent of Pando is properly fenced. Within this protected area, young aspen suckers are able to reach maturity and replace dying trees. However, around 50 percent of the stand remains unfenced, which means that growth in this area continues to falter.

Within the unfenced portion, the death of mature aspen stems creates gaps in the overstory, allowing sunlight to reach the forest floor. This, in turn, alters the composition of plant communities and reshapes the entire ecosystem.

Around a third of Pando was inadequately fenced until 2019, when the barrier was reinforced. Within this area, young shoots are now beginning to reach maturity, although the impacts of recent grazing are still strongly visible.

The diverging ecologies of the world’s largest living organism, an aspen stand called Pando. Image: Infographic Lael Gilbert

Essentially, Pando has become fragmented into three distinct zones, each of which is now progressing along a separate ecological pathway.

Summarizing this finding, study author Paul Rogers writes that “barriers appear to be having unintended consequences, potentially sectioning Pando into divergent ecological zones rather than encouraging a single resilient forest. Pando is effectively ‘breaking up,’ as evidence here shows distinct forests within the clone by protection status.”

In a statement, Rogers explained that more fencing probably isn’t the solution, and says that managers must instead try to control the population of grazing animals. “I think that if we try to save the organism with fences alone, we’ll find ourselves trying to create something like a zoo in the wild,” he said. “Although the fencing strategy is well-intentioned, we’ll ultimately need to address the underlying problems of too many browsing deer and cattle on this landscape.”

Concluding his analysis, Roger writes that the temporary cessation of livestock grazing and the culling of wild deer populations may be necessary to save Pando.

The study was published in the journal Conservation Science and Practice.

Source Link: The World’s Largest Living Organism Is Breaking Up