If you’re in the Northern Hemisphere and the skies are clear, you might get a few natural fireworks on New Year’s Eve. The Quadrantids meteor shower lasts from December 28 to January 12, peaking on January 3/4. It’s one of the best showers of the year in terms of the brightness and frequency of its meteors, but few people see it because it’s so cold outside for much of the world when it happens. A name that is hard to pronounce probably doesn’t help either.

Like all meteor showers, the Quadrantids are caused by debris from either an asteroid or comet, in this case the 2003 EH1, suspected of being a “dead comet”.

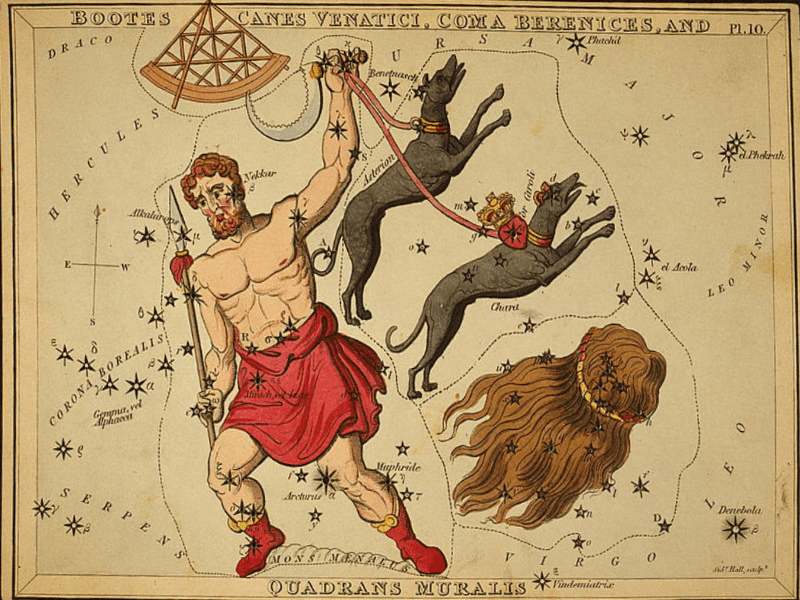

The first report of the Quadrantids dates back to 1825 when Antonio Brucalassi wrote: “The atmosphere was traversed by a multitude of the luminous bodies known by the name of falling stars,” which he identified as coming from Quadrans Muralis. The “wall-mounted quadrant” was a constellation in vogue with astronomers for more than a century before being left out by the International Astronomical Union. The radiant’s location is now considered part of Bootes.

Bootes the ploughman, with the obsolete quadrant pictured. Image Credit: Library of Congress, Public Domain, artist Hall, Sidney, etcher

This makes the shower below the horizon from most of the Southern Hemisphere. That’s unfortunate because conditions south of the equator are currently more suitable for lying outside and watching pieces of dust flame out above.

At high latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere, where the Quadrantids’ radiant passes almost overhead, the idea may seem less appealing around now.

However, if you’re somewhere tropical, experiencing an unseasonal warm spell, or just very well insulated, the Quadrantids can be breathtaking.

Meteor showers are measured by the Zenith Hourly Rate (ZHR), which counts the number of meteors visible under ideal conditions if the radiant is directly overhead. The Quadrantids sometimes have the highest ZHR of the year, for example in 2014 when their main peak was 245 on January 3, followed by a brief outburst of 315 a day later.

More typically, peak ZHR is usually around 80, which still makes it one of the three best showers, other than in a year where one of the more erratic events puts on a major show. The Quadrantids are also famous for the number of fireballs (meteors brighter than Venus).

There is, however, one fly in the ointment even for those in possession of heated jackets. The Moon will be full on January 6, making it bright enough to pose a problem around the Quadrantids’ peak. Early risers won’t necessarily be affected, as the Moon will set well before dawn on the peak night. Meteor showers are usually best after midnight anyway, as the turning of the Earth brings us towards them, rather than away.

Some meteor showers have a fairly bell-shaped curve to their ZHRs, but the Quadrantids usually have a short, sharp peak lasting just a few hours, with much lower numbers either side. For Europeans, that’s another reason to rise early on Wednesday morning, as the peak is expected at 3 am GMT. North Americans will see the peak on Tuesday night, hindering moon evasion.

Meteor showers are usually best appreciated with the naked eye, but the Virtual Telescope Project will be providing a screening of the peak for those unwilling or unable to venture out.

Source Link: The Year’s Most Underrated Meteor Shower Has Started, Peaking Next Week