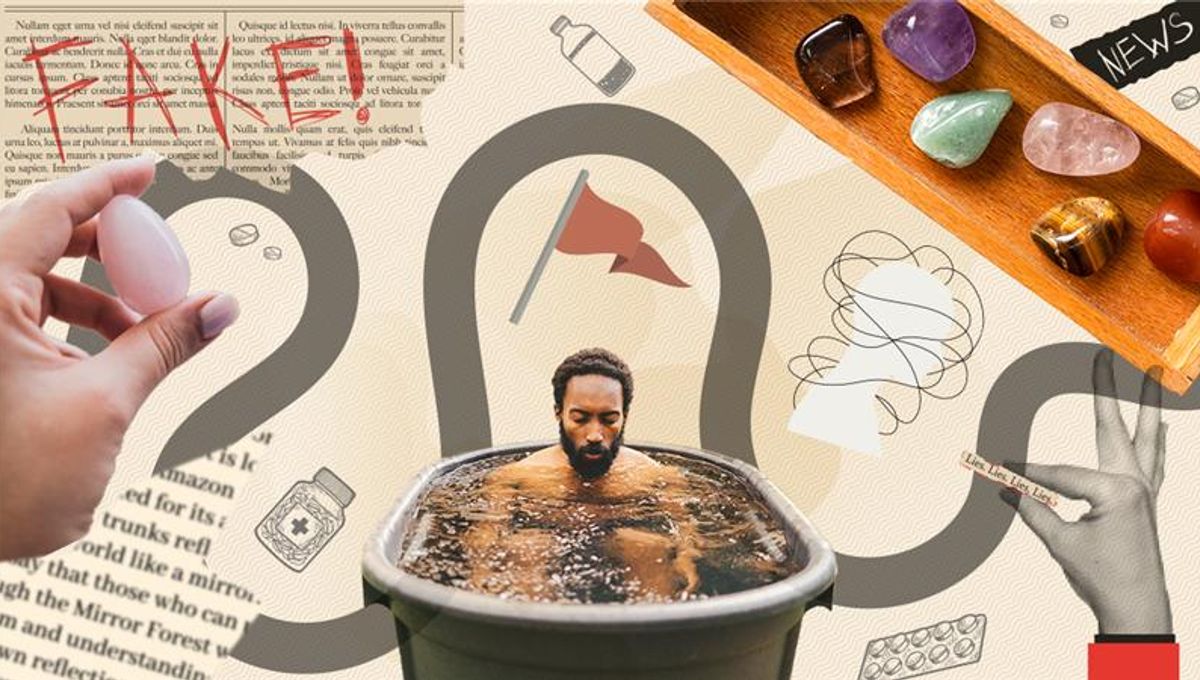

Wellbeing is a significant concern for many people across the world. However, it is also for sale – anyone who uses social media will be aware of the sheer number of organizations and individual influencers promoting competing wellness claims, from obscure supplements and 10-step programs to wisdom-peddling books, cold plunges, or premium spiritual retreats. These methods, designed to help you reach the “optimum you”, range in their degree of plausibility, from the acceptable or dubious to the downright batshit and bonkers.

At the same time, clinically recognized, empirically supported approaches to treating or improving mental health can themselves become lost in the broth of this pseudoscience soup. So how can we separate what is a legitimate scientific approach from what’s just another bunch of bollocks? Well, IFLScience recently spoke to Dr Jonathan Stea, a clinical psychologist and adjunct assistant professor at the University of Calgary, to find out.

Why is pseudoscience in the wellness industry a bad thing?

If you’ve ever experienced depression, anxiety, or any other related condition, then you may appreciate how challenging life becomes when your mental health is low. Everyday obstacles can become difficult trials, and our sense of self can shrink and wither as we withdraw from our hobbies or our friends and loved ones. And, unfortunately, the road to recovery can take time. Mental health is complicated; even evidence-based practices may not work for everyone, which can leave some people feeling isolated and confused when they cannot find solutions to their problems. This is also the time when we can become more susceptible to bogus claims – especially if we are desperate for a result.

Over the last decade, the wellness industry has bloated to the point that it was estimated to be over $4.3 trillion US dollars in 2020, and may reach $8.5 trillion by 2027. Increasingly, it seems, people are seeking ways to improve or take control of their overall health, especially their mental health. But this industry is filled with bogus claims and tinctures and tonics that would make a snake oil salesman blush. While it may be easy to dismiss it all as some harmless quackery, there is a darker reality to this kind of pseudoscience that has serious implications.

Pseudoscience is “a big problem”, Stea, the author of Mind the Science: Saving Your Mental Health from the Wellness Industry, a new book that raises the concerns about psychological misinformation and pseudoscience in the wellness industry, explained. “It’s harmful in at least three ways. It can be directly harmful as a result of the treatments being used.”

This includes common instances where pseudoscientific practices simply don’t work and worsen patients’ mental health symptoms, but it also includes rarer instances where a supposed treatment kills a patient.

“Then pseudoscience is indirectly harmful because it can take hard earned time and money away from people. It can, you know, be very emotionally and financially exploitive in that way. And while their time is being taken away, their mental health symptoms could again be getting worse, because they could be spending that time seeking evidence-based care.”

The third way that pseudoscience is harmful is much broader and speaks to issues facing society more generally, especially when it comes to the public trust in science as an institution and scientists as individuals.

“[T]olerating pseudoscience is just unhealthy for society at large”, Stea added. “I think we really did witness that in the pandemic. My favorite example is [seeing] how the wellness industry capitalized on just a lot of anti-vaccine sentiment in the anti-vaccine movement.”

The battlefield of misinformation and pseudoscience

Although mis- and disinformation – the former being inaccurate or false information while the latter is deliberately misleading information – within the realms of health industries is far from new, there has been a distinct rise in it since the COVID-19 pandemic. This situation has been made worse by social media, which often proliferates spurious claims.

For instance, a study conducted in 2022 found that more than half of the most popular TikTok videos discussing ADHD contained misinformation. Moreover, only a fifth of these videos were considered “useful” by researchers.

More recently, Stea collaborated with Marco Zenone, a public health researcher who examines misinformation and online portrayals of health and wellness issues, on a forthcoming study. Zenone wanted to know how useful and accurate videos that use specific hashtags were for viewers.

“[Zenone] asked me to come on board to the study where [we] looked at the top 1,000 videos on Tiktok with the hashtag #mentalhealth.”

“[W]e looked at it at a particular time frames in October 2021 […] and found that about a third, so 33 percent, were misleading,” Stea explained.

Most of the videos involved users sharing their personal stories or views, but the third of the videos that presented misinformation essentially regurgitated old anti-psychiatry tropes, such as the idea that medication is harmful and part of a conspiracy to extort patients.

Worryingly, Stea, Zenone, and colleagues found that the misleading videos were shared, liked, and commented on more than the videos the scientists considered accurate. This is a disturbing point when you consider that #mentalhealth has been accessed over 107 billion times on TikTok, according to Stea.

“That, to me, just attests to how far reaching these videos are”, Stea added.

“It speaks to the idea that, you know, social media isn’t going anywhere. And so it’s sort of a call for science communicators. We need more of them. We need an army. We need to be better organized to kind of go on the front line, so to speak, in the trenches, and creatively find ways to debunk mental health misinformation or just misinformation in general.”

How do we spot misinformation and pseudoscience?

The problem with identifying pseudoscience is that, sometimes, it can appear very convincing. Like a Trojan horse containing healing crystals, pseudoscience practitioners wrap their dodgy claims in scientific terminology to sound impressive and trustworthy. “Energy”, “the electromagnetic field” and “quantum” are all words that get misused/exploited in the wellness industry.

If you are not scientifically literate, how do you decide whether quantum computing, an area of computer science, is any more or less legitimate than so-called “quantum healing”? Or, within the context of mental health, how do you discern between Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and Exposure Therapy, two evidenced-based therapies, and something like Thought Field Therapy (TFT) or Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP), or Rebirthing Therapy? These latter three are all dressed in sciencey-sounding trappings but lack any evidential substance.

This is the challenge many face when dealing with the sheer number of competing products or supposed therapies available to address mental health issues. It can be overwhelming and intimidating, and unfortunately, there is no single criterion that tells us whether something is an evidence-based practice, discipline, or treatment, or whether it is just a fancy-sounding crock of crap.

This is where Stea’s work, especially his new book, can be of use. Stea has identified nine red flags that can help readers determine the likelihood that they are dealing with something dodgy. For instance, this could include the overuse of “ad hoc hypothesis”, explaining away negative results. This may involve statements like “Oh it didn’t work because you didn’t believe enough”.

Another red flag is the reverse burden of proof, whereby the person receiving a statement is expected to prove it wrong. This is usually articulated as something like “Prove to me that putting coffee up my anus isn’t good for me.”

Equally, any practice or treatment that avoids the peer review process or relies purely on confirmation cases, mostly from anecdotal accounts – “I have a friend of a friend who really benefited from crystal healing” – then you are likely dealing with pseudoscience.

“I’m hoping the book will help empower and embolden people to take their mental health into their own hands so that they feel better equipped to protect themselves from mental health misinformation and mental health pseudoscience. And not just for themselves either, but for their loved ones and everyone else,” Stea explained.

The internet and the world of social media will likely remain a fraught battlefield filled with misinformation and even dangerous ideas drawn from the wellness industry, but being armed with more ways to recognize it may help limit its spread.

All “explainer” articles are confirmed by fact checkers to be correct at time of publishing. Text, images, and links may be edited, removed, or added to at a later date to keep information current.

The content of this article is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of qualified health providers with questions you may have regarding medical conditions.

Source Link: There’s A Lot Of Misinformation And Pseudoscience In The Wellness Industry, Here’s How To Avoid It