It soon will be the 30th anniversary of my decision to become a space scientist (before then, the dream was palaeontologist – not that I am over dinosaurs, mind!) and since then I have devoured any astronomy image I have come across. Small, big, detailed, or pixelated, there is so much wonder out there and I can’t get enough.

Science communicators from other disciplines often joke that engaging the public with astronomy is easy because we have so many pretty pictures. There is certainly truth in that. But I believe that there are also other factors. Astronomy is as old as the human race. If we were looking at the sky, we were doing astronomy. And through astronomy we will also get closer to some of the big dilemmas of humanity: why are we here? Are we alone? Etcetera, etcetera.

Space images might not be worth a thousand words, but together with the insights of scientists and communicators, they build an extraordinary narrative for our understanding of the universe and our place in it. These are some of my favorite images. I’m certain there are many that have higher scientific value, but these are special to me.

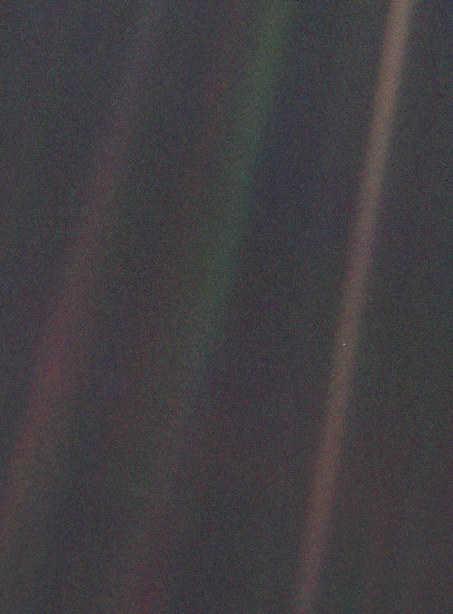

Pale Blue Dot

The blueish pixel in the rightmost light beam is the pale blue dot.

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Probably the worst picture of our planet ever taken and obviously the most iconic. Taken by Voyager 1 from a distance of 6 billion kilometers (3.7 billion miles), Earth is just a pixel within that image, truly evocative of just how empty space is. The photo was taken as the result of astronomer and communicator Carl Sagan asking NASA to turn the Voyager camera around and snap back at the Solar System.

The image itself is of the uttermost simplicity, but it is Sagan’s words that raised it to iconic status. The whole comment on it is poetry and science, and I can’t help tearing up reading it no matter how many times I’ve read it before.

“Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every “superstar,” every “supreme leader,” every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there – on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.”

Sagan set an impossibly high bar for every science communicator ever since. How are we meant to compete with the line “on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam”?

The Face of Mars

The region of Cydonia as seen by Viking 1 in 1976.

Image credit: NASA

There was one space image that had such a chokehold on my childhood that there could be no competition there: the Viking 1 orbiter view of Cydonia and the mysterious “face on Mars”. Long before I knew about pareidolia, the tendency of humans to see faces everywhere, I knew there was a face looking at us from Mars. Unlike H.G. Wells’ Martians, the face was not regarding the Earth with envious eyes. It was simply looking up.

The iconic image is from 1976 but it took decades for follow-up observations of high enough quality to deliver the true features of the Face of Mars – a windswept hill eroded in such a way that it could be mistaken for a face.

A valuable lesson in the scientific method. Follow-up work is definitely as important as the original, and often delivers more insights, challenges some expectations, and even alters the conclusions.

A higher-resolution view of The Face reveals that the features we spotted were nothing more than slopes.

Image credit: By NASA / JPL / Malin Space Science Systems

Supernova 1987A

I am lucky that my family was very supportive of the growing obsession I had with space. Back in 1996, I went on holiday with my grandparents and they took me to a bookshop to pick a book to bring with me. I saw one book and I knew it was the one. I still have it. Margherita Hack’s L’Universo Alle Soglie Del Duemila (The Universe at the Threshold of the Year 2000). The cover had an extremely pixelated view of Supernova 1987A, taken just three months after Hubble was fixed in 1994.

Supernova 1987a as seen by Hubble in 1994.

Image credit: Dr. Christopher Burrows, ESA/STScI and NASA

The image was cutting edge. And weird. The overlapping rings made it look a bit like an arcane symbol. What kind of magic was hidden within? This was the first supernova that modern astronomers were able to study in great detail, the closest to Earth since 1604. But it wasn’t that close. It took place in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a small galaxy satellite to the Milky Way.

The supernova is encircled by three rings of glowing gas. They are not really intersecting in real life, they are on different planes, but we are seeing the system at an angle. The central ring is in the plane of the supernova; the wider ones are one in front and one behind.

The progenitor star released material during its red and then blue giant phases. This material should have been organized in an hourglass shape. The presence of the rings is unexpected and one explanation is that radiation is highlighting these rings around the hourglass.

Hubble and JWST deep fields

The original Hubble Deep Field.

Image credit: Robert Williams (NASA, ESA, STScI)

What do you hope to find looking at a patch of empty sky? Astronomers in 1995 hoped for something. The concept was the Hubble Deep Field, a series of hundreds of observations focused on a tiny patch of the sky where no stars or other sources were known to exist. The result of those many hours created a spectacular image.

Within it, astronomers found 3,000 galaxies that had never been seen before. Some of them were among the most distant and youngest known to humanity – an incredible achievement, and the beginning of a new approach to studying the most distant universe.

There are 50,000 infrared sources of light captured in this spectacular image.

Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, I. Labbe (Swinburne University of Technology), R. Bezanson (University of Pittsburgh), A. Pagan (STScI)

Many deep field views are available to astronomers now. A more recent one from JWST had 50,000 sources, most of them galaxies, some of which were at an even greater distance (and so much younger) than what had been seen by Hubble.

Supermassive Black Hole M87*

The first view of M87*

Image credit: EHT Collaboration

Based on the comments on Pale Blue Dot, you’ll know that I easily get emotional about space images. And there was another iconic time for me to get emotional: the unveiling of the first image of a supermassive black hole. To provide you with some insights into how the sausage is made, I wrote the article from the airport and then from the plane I was taking to get me to a conference.

We are often given news and studies a few days in advance, but not this time, so there was a lot of adrenaline at work to make sure the article was out as soon as possible. When I clicked submit, the captain announced that we would be slightly delayed, but I didn’t care. I was hypnotized by the beauty of it all. The tears rolled down my cheeks while staring at that orange and black image. My neighbors on the flight asked if I was ok. Potentially a big mistake on their part, because I went into an impromptu lesson on why that image is iconic.

Let’s be honest: if you do not know about it, it is just a fuzzy glow. But that glow is the light of matter just as it falls into a supermassive black hole. A supermassive black hole that weighs 6.5 billion times our Sun. Located in a galaxy over 50 million light-years away. And it was only possible because we connected radio telescopes across the world, all pointing at the same object, a global effort that resulted in an incredible image. An image worth more than a few tears.

Sunlight glistening on Titan

Titan in infrared, with sunlight glinting off of Titan’s north polar seas.

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona/University of Idaho

I had a personal connection to the Cassini mission. The spacecraft that orbited Saturn for 13 magnificent years was a collaboration between NASA, the European Space Agency, and the Italian Space Agency. The agencies announced a plan to get signatures from people across the world and put them on a CD-ROM to be inserted in the spacecraft. If you think that having those on a CD is dating me, consider that I had to send my signature via fax (remember those?). Together with 616,419 other people, I wished Cassini well.

I loved the mission. The incredible discoveries and insight into the system included the hydrothermal activity on icy moon Enceladus, a place where life might exist beyond Earth. But my heart is on Titan. The largest moon of Saturn has a thick atmosphere, which gives it an orange color. Well, looking at it in visible light – in infrared is different.

Titan has rain, rivers, lakes, and seas. They are not made of water, but hydrocarbons. And those thick orange clouds let the infrared light through. Cassini caught the glistening of the Sun on the surface of a lake on a distant world. Astronomy, for me, is to discover what is out there, to understand our little corner of the cosmos. And this image is both alien and familiar. It’s a lake of methane on a distant moon only visible through light we cannot see. And yet, it’s a little sunlight, reflected and sparkling, like it does on the sea on a summer day on Earth.

Source Link: These Are Some Of Our Favorite Space Images