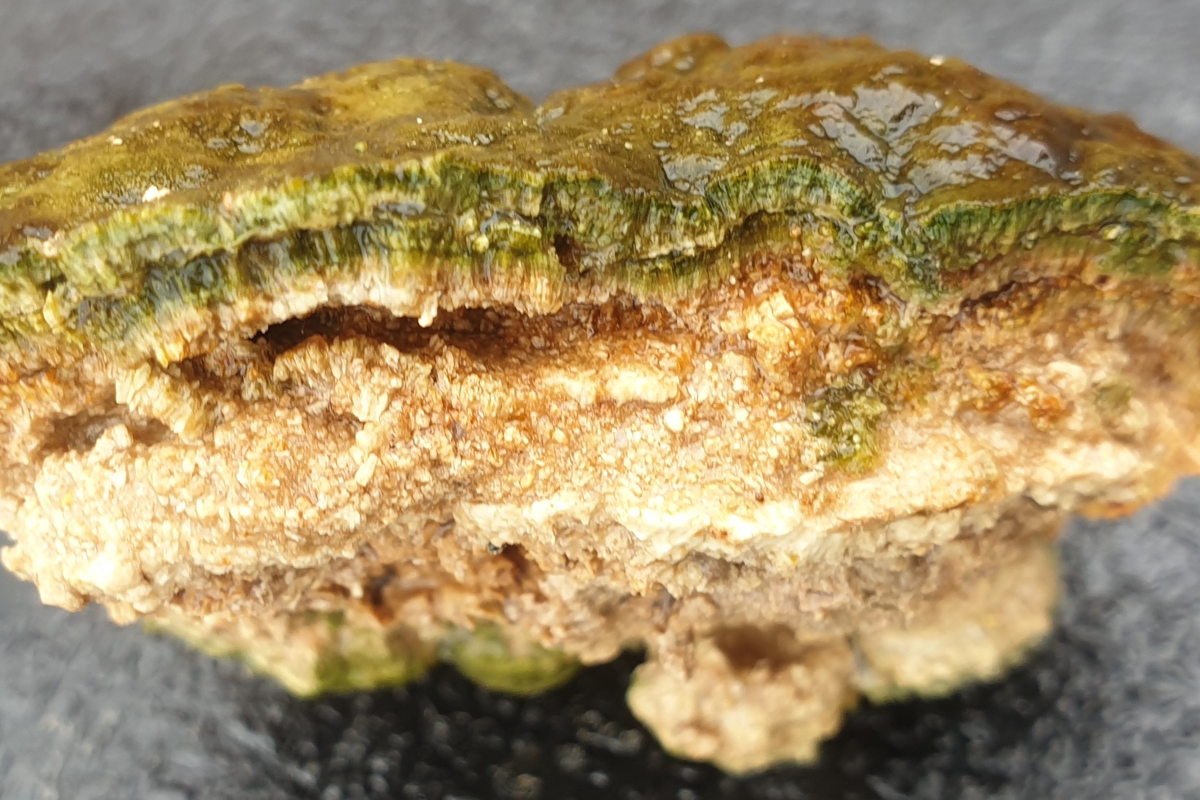

Communities found in South Africa called microbialites look like green-tinged rocks, but they grow. Although they resemble some of the oldest evidence for life on Earth, new evidence indicates they are growing much faster than we thought, and drawing abundant carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as they do it – even at night.

As their name suggests, microbialites are microbe mats, which deposit carbonate mud and turn it into calcium carbonate. They once dominated life on Earth, forming enormous bands of limestone. Since the Cambrian explosion, however, competition and consumption by more active life has seen them confined to limited locations, particularly those that are too salty for other life. Stromatolites are the most famous examples, distinguished from other microbialites by their layered structures.

Microbialites have generally been considered to be interesting for what they could tell us about Earth’s past, but not a significant factor in life on Earth today, merely hanging on by the microbial equivalent of fingernails. A new study challenges that, reporting that some microbialites are constructing rocks at an unexpected pace, and storing a surprising amount of carbon as they do so.

“These ancient formations that the textbooks say are nearly extinct are alive and, in some cases, thriving in places you would not expect organisms to survive,” said Dr Rachel Sipler of Rhodes University in a statement. “Instead of finding ancient, slow-growing fossils, we’ve found that these structures are made up of robust microbial communities capable of growing quickly under challenging conditions.”

Sipler and colleagues measured the growth of four microbialite communities, two of them stromatolites, in southeastern South Africa. They are precipitating so much calcium carbonate that they could grow 13-23 millimeters (0.5-0.9 inches) a year were they not fighting against weathering, much faster than comparable communities elsewhere in the world.

That may not sound like much in comparison to plants, but the rocks they make are so dense that these microbialites are packing away 9-16 kilograms of CO2 per square meter (2-4 pounds CO2 per square foot) per year. This is hundreds or thousands of times the rates measured for stromatolites and microbial mats elsewhere in the world. It’s also much more than established tropical rainforests (0.1-0.2 kg CO2/m2y-1) or even seagrass meadows.

Moreover, forests, marshes, or grasslands are constantly in danger of giving up the carbon they have captured if a fire sweeps through or they even dry out. Unlike diamonds, calcium carbonate may not quite be forever, but it goes close, as proven by vast limestone provinces up to 2.8 billion years old laid down by these microbialites’ ancestors. Some of the deposited carbon is in the more vulnerable organic form, but up to 87 percent is inorganic.

Sadly, that doesn’t mean microbialites are the magic bullet to extracting atmosphere carbon dioxide. After all, microbialites in general only live in quite limited places today, and the ones Sipler and colleagues studied are more restricted still. They live in areas where “hard water” rich in calcium seeps from coastal sand dunes, giving them access to plenty of the other ingredient needed to turn carbon dioxide to stone.

Moreover, even at their relatively rapid rate of carbon processing, it would take about 40 million square kilometers (16 million square miles) to balance all the CO2 we are putting in the air – that’s an area equal to Africa and the USA combined.

It’s astonishing how fast these rocks grow, but they’re not a get-out-of-jail-free card for carbon emissions.

Image credit: Thomas Bornman

Yet even if the practical uses are limited, these communities remain a marvel. “The systems here are growing in some of the harshest and most variable conditions,” Sipler said. “They can dry out one day and grow the next. They have this incredible resiliency that was compelling to understand.”

Moreover, the way these microbialites grow is unexpected and remarkable. It takes energy to drive the chemical reactions the microbes are performing, and this was assumed to come from sunlight, with the limestone formation representing a form of photosynthesis. However, the team found 80 percent as much carbon dioxide is being removed from the air at night as during the day, indicating that after dark the microbialites are using energy from one chemical reaction to induce another.

That’s more similar to what occurs around deep-sea vents than under the open sky, although unlike at those vents, photosynthesis is also part of the process. The team studied the DNA of the microbes that make up the communities and found genes for photosynthesis, but also some they suspect control other forms of carbon processing.

Sipler said the expectations of the scientific community about microbialite behavior were so wrong it would have been easy for the team to miss the real story. She attributes their success both to persistence in rechecking all their observations many times, and the team’s diversity. “You never know what you’re going to find when you put people from different backgrounds with different perspectives into a new, interesting environment,” she said.

The study is published open access in Nature Communications.

Source Link: These “Living Rocks” Are Among The Oldest Surviving Life And Are Champion Carbon Dioxide Absorbers