We’ve been getting the mouthparts of theropod dinosaurs like T. Rex wrong for over a century, a new study claims. If any of their victims had been foolish enough to look back while being chased, they would not have seen some of the most fearsome teeth ever formed coming for them, at least while the theropod’s mouth was closed. Instead, a thin set of scaly “lips” hid the horror of what was to come.

Palaeontologists face the never-ending problem that skin and soft organs seldom fossilize, so animals must be reconstructed based on bones and teeth, with a little extrapolation from living species. Once artistic renderings are done, they often settle in the general public’s consciousness and prove very hard for subsequent evidence to displace.

Some of our most iconic dinosaur images involve T. Rex and other apex predators with exposed teeth, a conclusion possibly based on the permanent, and not at all reassuring, smile of the crocodile. However, this view has been challenged in a new paper.

Komodo dragons, the other large reptilian predator of the modern era, have the grace to hide their sharp teeth behind soft facial tissues. Dr Thomas Cullen of Auburn University and co-authors wondered if there was any reason to expect theropods to be more aligned with crocodilians than Varanidae, other than large members of the former being much more common and familiar today.

We may not have any soft tissue legacy to settle the question, but we do have plenty of theropod teeth, and the authors noted the enamel on these is relatively thin. That might not matter if you shed your teeth frequently like a shark, but there is evidence theropods, at least the larger ones, kept their teeth for a long time.

That gave T. Rex and friends (ok, cousins) an incentive to look after their incisors. Not possessing dental floss, and lacking the arms to apply it anyway, they would have needed other solutions, the authors reasoned. Protecting mouthparts from the open air when not in use would have been a good start.

Cullen and co-authors compared the skull length and tooth size of various dinosaurs and living reptiles. They also examined the wear patterns of the teeth.

A theropod skull, and a comparison of reconstructions using crocodilian-like lipless jaws, or a lizard-like lipped mouth, from two angles. Image credit: Mark P. Witton

The paper concludes theropods kept their teeth inside their mouths. The lack of surface wear on tyrannosaurid teeth in comparison with those of modern crocodiles is particularly suggestive. The authors consider this an indication the dinosaurs kept their teeth hydrated with saliva, which would have been very inefficient if it meant non-stop drooling. Far more likely that some sort of covering protected the gnashers from the elements. Crocodiles don’t need to do this because they have thicker enamel.

Moreover, despite the size of some ancient killing machines’ teeth, the tooth-to-jaw ratio indicates keeping them protected would have been entirely possible. The authors suggest this was done through a set of thin, scaly lips, known as labial scales.

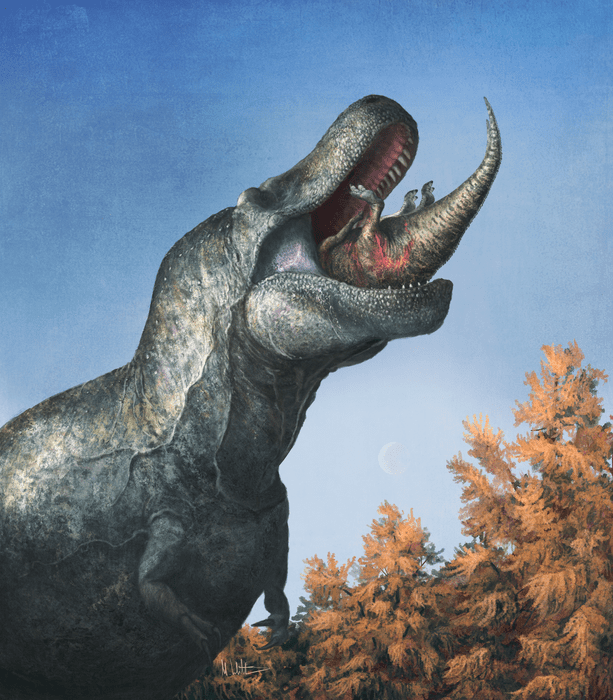

A T. rex eating a juvenile Edmontosaurus looks unfamiliar now the lips have been added. Image credit: Mark P. Witton

The authors note that they have found evidence for a “superficially cheek-like structure” that covered the teeth of ornithischians. These were herbivorous dinosaurs however, and nothing similar is known for theropods. Moreover, even though Komodo dragons may look more like a T. rex than crocodiles do, they are actually more distant relatives.

Nevertheless, the evolutionary distance between theropods and any species alive today is so large that bracketing them with crocodiles is likely to be misleading, and it’s better to rely on physical evidence such as tooth wear.

The study is published open access in Science.

Source Link: Thin-Lipped Tyrannosaurs Hid Their Most Fearsome Weapon