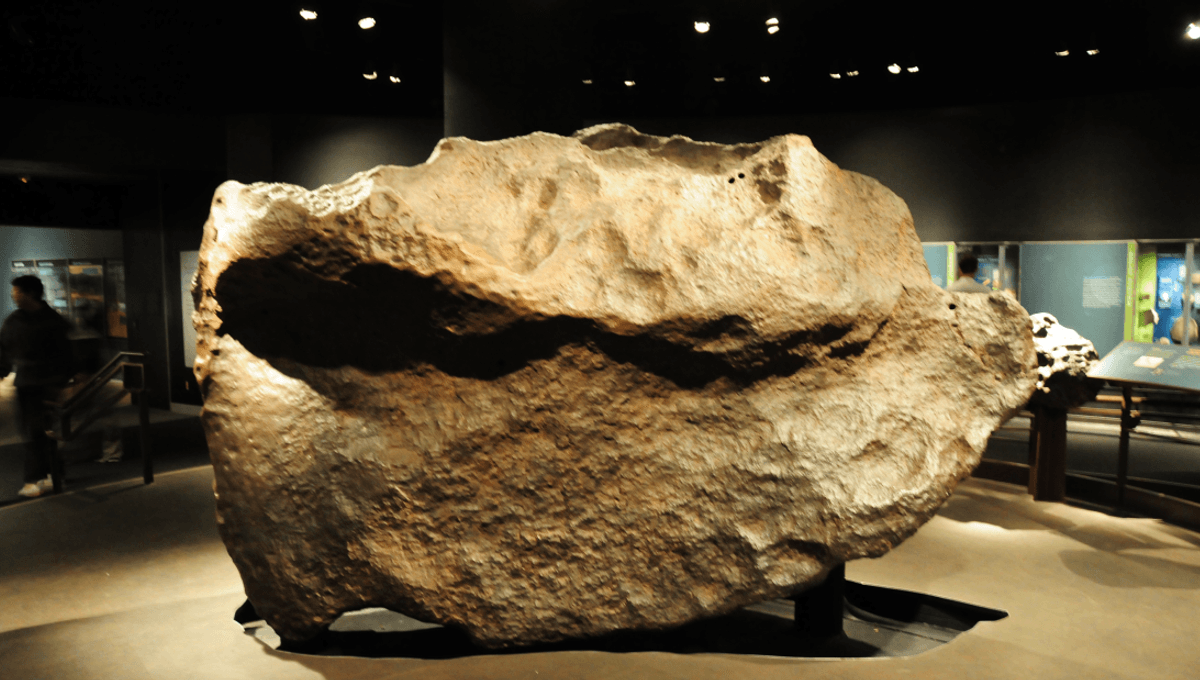

Step into the American Museum of Natural History’s Hall of Meteorites and you’ll be faced with a monster. It goes by the name Ahnighito, the largest fragment of the Innaanganeq meteorite (also known as the Cape York Meteorite) that’s so heavy, its supports go into the bedrock beneath the museum building to keep it stable.

At 34 tons, it’s up there with the largest bits of meteorite known to science. It was once the middle of an asteroid that broke apart and is almost as old as the Sun, dating back around 4.5 billion years.

Ahnighito was zooming around in space until around 10,000 years ago, when it crash-landed in what we now know as Greenland. Flash forward to 1894 and Western explorer Robert Peary became the first non-native Arctic explorer to lay eyes on it, but it had been a big deal to humans for a long time before this.

It had been a source of metal for Inuit for thousands of years

Jack Ashby

“It was found in Greenland, on the Cape York of Greenland,” Assistant Director of the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge, Jack Ashby, told IFLScience. “It’s one of those [where] people will say it was discovered in the 1890s, but what they mean is it was discovered by Western scientists in the 1890s. It had been a source of metal for Inuit for thousands of years. So, when the Cape Meteorite, or that fragment of it, was taken to New York, it was taking a resource away from the Inuit people to the museum.”

Transporting the 34-ton meteorite from Greenland to New York was only half the battle, as once it arrived at the museum, the next consideration was how to house it in a building without destroying that building. To overcome this, a support base was built with beams that go into the bedrock beneath the museum, meaning the weight of the meteorite isn’t on the floor but on the structures that sit beneath it.

Ashby raises the curious case of the whopping great meteorite in his latest book, Nature’s Memory, as an example of why the majority of dinosaurs on display in museums are made up of casts rather than the real fossils. Put simply, most buildings just aren’t up to supporting the enormous weight of dinosaur fossils that, being made up of stone, are incredibly heavy.

Several tons on a wooden – typically Victorian – museum floor, is a very risky thing to do

Jack Ashby

“When you’re thinking about displaying a dinosaur skeleton, the load bearing of the floor – like the meteorite – it’s going to be really significant in how you go about doing that,” said Ashby. “And unlike a meteorite, it’s not one big solid rock. It’s potentially hundreds of bones. So, it’s quite hard to scaffold that and support the weight and that is one reason why it’s rare to see a real large dinosaur on display just because they’re so heavy. Several tons on a wooden – typically Victorian – museum floor, is a very risky thing to do.”

In most cases we only retrieve a small fragment of a dinosaur anyway, which is why skeletons like the impressive Patagotitan at the Natural History Museum, London, are actually a combination of several animals’ remains put together to create an approximation of one individual. Working out the logistics and best way to represent incomplete and enormous specimens like dinosaurs and Ahnighito is just one of many curious decisions that have to be made by museum staff, and Ashby explores humans’ influences on natural history collections in depth in Nature’s Memory. Like the sound of it? Catch an exclusive extract in the May issue of CURIOUS, IFLScience’s e-magazine.

Source Link: This 34-Ton Lump Of Space Rock Is The World's Largest Meteorite On Display In A Museum