When it’s time for Megasyllis nipponica to spawn, its butt swims off. Technically called a stolon, the annelid worm’s rear end sprouts eyes and swimming equipment to depart the adult body on which it developed and go in search of the opposite sex.

These worms have adapted an approach to reproduction that sees them jettison their rear end, a segment that’s equipped with gonads, so that it can go it alone to spawn in a process known as stolonization. With eyes, antennae, and swimming bristles, the detached stolon can swim autonomously, leaving its gonadless body in the dust.

It’s a bizarre life cycle that’s had scientists scratching their heads. How does the “head” of the stolon develop in the mid-body of the adult worm? Researchers decided to find out by combining histological and morphological observations to see in what order the changes took place, and what mechanisms could be driving them.

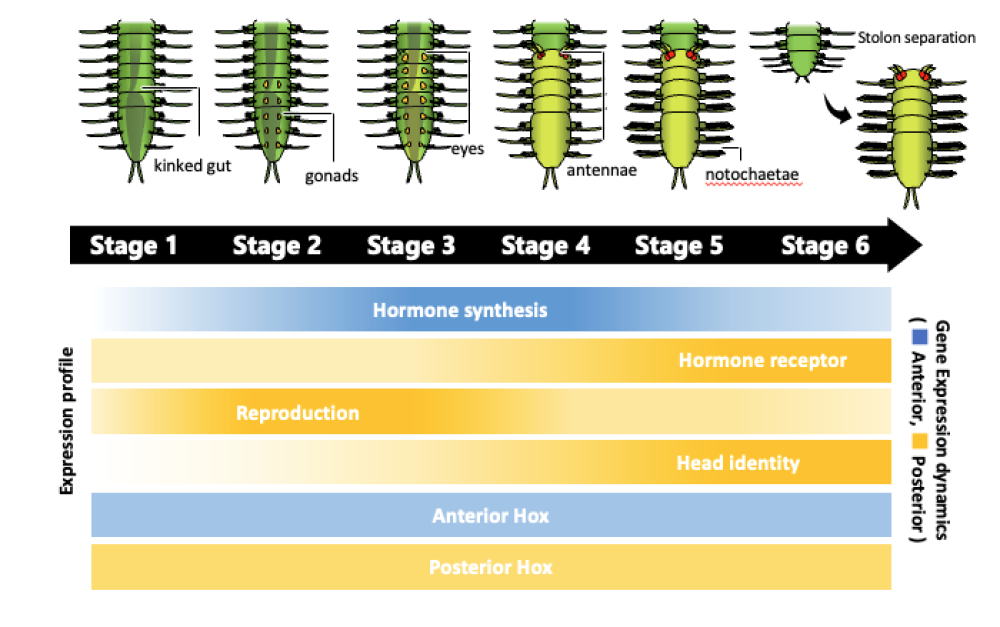

Their investigations revealed that the first step involves the formation of gonads at the worm’s butt end. Next comes the stolon’s “head” which develops in the worm’s midriff, the place where eventually the stolon will detach itself. The stolon holds on long enough to develop nerves and a “brain” that enables it to sense and react autonomously.

The next step was to dive into the gene expression that could be driving this transformation from the rear end of a worm to a self-driving gamete delivery service. The team discovered that a group of head formation genes that are well documented in the head regions of other animals was found at the point on the worms’ bodies where their stolon’s “head” would develop.

It seems the expression of these genes is associated with gonad development in M. nipponica. “This shows how normal developmental processes are modified to fit the life history of animals with unique reproductive styles,” explained study lead Professor Toru Miura from the University of Tokyo in a statement.

As for why the stolon developed a “head” but no body (it doesn’t have a digestive tract, for instance), it seems this may be to do with the expression of genes that remain active even while the rear body segment of the worm is getting ready to go solo.

The top illustration shows staging based on morphological characteristics. The lower bands show the transitions in gene expressions upregulated in anterior (blue) and posterior (orange) body parts.

“Interestingly, the expressions of Hox genes that determine body-part identity were constant during the process,” continued Miura. “This indicates that only the head part is induced at the posterior body part to control spawning behavior for reproduction.”

The team will continue their work into sex determination and endocrine regulation in syllid worms like M. nipponica (and the many-butted King Ghidorah worm), but this marks the first time we’ve been able to crack how these worms’ butts swim off and spawn without their bodies. Suddenly dating apps don’t seem so messed up.

The study is published in Scientific Reports.

Source Link: This Worm’s Rear End Sprouts Eyes And Swims Off When It’s Time To Mate