An interdisciplinary team of researchers have used digital imaging techniques and scientific instrumentation to answer an enduring question: what did the famous Parthenon sculptures look like when they were originally made? The results reveal these ancient sculptures were elegantly painted, with different colors and multiple patterns and designs.

The Parthenon sculptures, sometimes called the Parthenon marbles, are a collection of various marble architectural decorations that were created for the temple of Athena (the Parthenon) on the Acropolis in Athens, Greece. Since the early 19th century, these wonderful examples of ancient artistry have been living in the British Museum, a situation that has become controversial in recent years.

But this controversy aside, since their discovery, generations of scholars from various fields have examined them and tried to figure out what they would have looked like when they were first created. Today, the sculptures are plain and paint-free, showing no hint of color. As such, people thought they were originally colorless, which has meant any surviving paint was subsequently removed by historic restoration efforts that sought to return the sculptures to their assumed “whiteness”.

This has made it difficult for scholars to reconstruct their original appearance.

“The Parthenon sculptures at the British Museum are considered one of the pinnacles of ancient art and have been studied for centuries now by a variety of scholars,” lead author Dr Giovanni Verri, from the Art Institute of Chicago and formerly a Mellon Fellow at the British Museum, explained in a statement sent to IFLScience. “Despite this, no traces of colour have ever been found and little is known about how they were carved.”

To address this, Dr Verri and a team of researchers from the British Museum and King’s College London, which consisted of scientists, conservators, textile historians, and archaeologists, conducted visible-induced luminescence imaging on the marbles.

This technique is a noninvasive method that the team used to detect microscopic traces of a pigment called Egyptian blue – an ancient human-made pigment that comes from calcium, copper, and silicon. This pigment was being used in Egypt as early as 3000 BCE and was pretty much the only blue used in Greece and Rome.

The famous Parthenon sculptures are often thought to have been created without color, but new analysis reveals just how vibrant they really were.

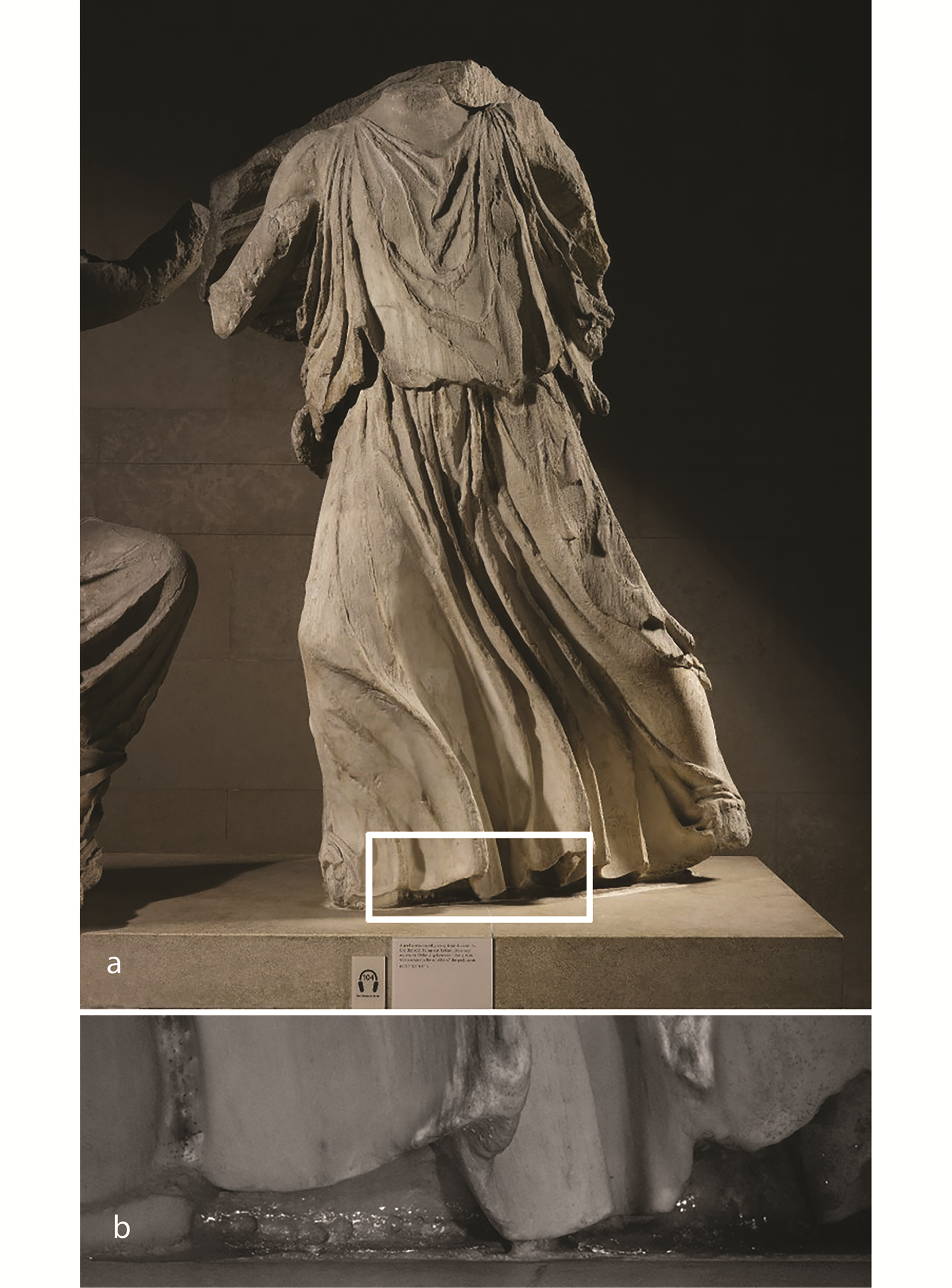

Image courtesy of © Trustees of the British Museum

The team found traces of Egyptian blue on the Parthenon sculptures, which revealed how they had originally been covered with elaborate floral designs on their garments. They also found traces of white and purple on the sculptures, the latter of which was a valuable pigment in the ancient Mediterranean world.

Interestingly, it seems the artists who created the figures made little effort to give them a special surface to allow the paint to adhere. Instead, it seems they focused solely on reconstructing the intended form, be it wool, linen, or skin.

“Even if the surfaces were not explicitly prepared for the application of paint, however, carving and colour were unified in their conception. The Parthenon artists were sympathetic to the final intended polychrome sculpture providing surfaces that evoked textures similar to those of the subjects represented. It is likely that the painters took advantage of these mimetic surfaces to achieve the final effects,” said Dr William Thomas Wootton from King’s College London.

This work demonstrates that the Parthenon sculptures were far more elaborate and vibrant than previously thought. It demonstrates that the color, as well as the sculptures’ form, were both as important for ancient Greek artists.

“The elegant and elaborate garments were possibly intended to represent the power and might of the Olympian gods, as well as the wealth and reach of Athens and the Athenians, who commissioned the temple,” said Dr Verri.

The white arrow indicates where samples were taken for further analysis.

Image courtesy of ©Trustees of the British Museum

He added, “The painting is certainly contemporary to the building, as we could see clear traces at the back of the sculpture. After being placed on the building, the back would have no longer been accessible. We can only speculate as to why they painted the back.”

One possible explanation could be that the sculptures were dedicated to the gods who, unlike human viewers, were supposedly capable of seeing them from all angles. Alternatively, the artists themselves may have wanted these details included in the interests of completeness.

It is also possible that the Parthenon sculptures inspired and influenced the use of color for other contemporaneous and later works.

“It could be argued that the Parthenon was partially or wholly the inspiration for a wider interest in the use of rich and elegant polychrome sculpture. This interest has clear parallels in other media, including terracotta figurines and textiles, which are reported in written sources to have featured figurative designs,” Dr Verri suggested.

The study is published in the journal Antiquity.

Source Link: True Color Of The Parthenon Sculptures Revealed By Cutting Edge Technique