Chessboards have inspired many brainteasers over the years. For example: given a standard chessboard and a knight, is it possible to move the piece such that it visits every square once and only once? The answer is yes – and that fact might end up helping in the struggle against climate change.

In mathematical terms, this “knight’s tour”, as the problem is known, is an example of something called a Hamiltonian cycle. But what if, rather than a regular chessboard, the knight was traveling round something more, well, wonky? Something like… a quasicrystal?

If you haven’t heard of quasicrystals, that’s not surprising. Only three have ever been discovered occurring naturally, and all of them were found in a 4.5-billion-year-old meteorite in a remote corner of Siberia. Technically, the term refers to a structure that is ordered but not periodic, the atoms form a pattern but the pattern does not repeat perfectly – to put it crudely, it looks like a regular crystal, so long as you squint.

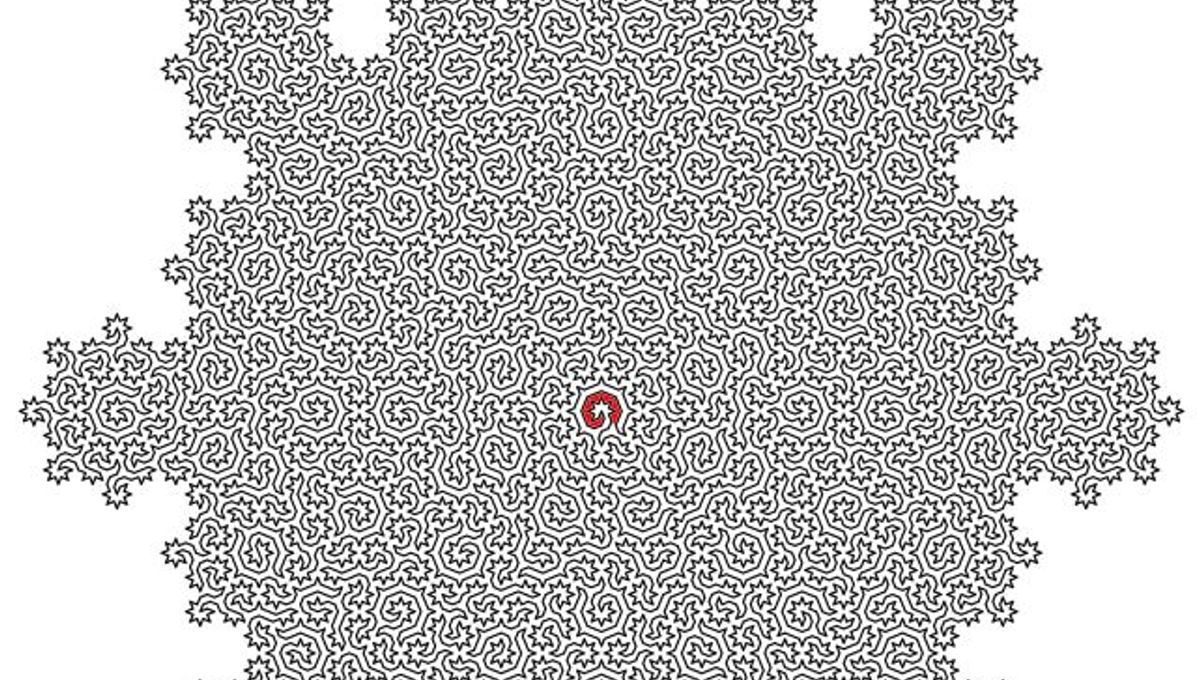

But this irregular nature means that any tour around a quasicrystal will be very special indeed: they’re fractal in nature. “When we looked at the shapes of the lines we constructed, we noticed they formed incredibly intricate mazes,” explained Felix Flicker, Senior Lecturer in Physics at the University of Bristol and lead author of a new paper on the discovery, in a statement.

“The sizes of subsequent mazes grow exponentially – and there are an infinite number of them,” he said.

So why is this important? Well, finding these Hamiltonian cycles around the atoms of crystals is normally a difficult-to-the-point-of-intractable problem – which is a shame, because it has some really important applications. Adsorption, for example: no, that’s not a spelling mistake – it’s a chemical process in which atomic particles are removed from gases or liquid solutions by becoming adhered to the surface of a solid.

It’s also indispensable throughout industry. Adsorption is key in the dyeing process; in softening hard water and conserving it where water is scarce; in pharmaceutical manufacture and the food industry; it’s even the process that makes activated charcoal such a mixed blessing. In the modern, climate-change-addled world, it also has one particularly intriguing application: it can be used for carbon capture and storage, keeping dangerous CO2 molecules from entering the atmosphere.

The problem is that, so far, industrial adsorption relies on crystals – the regular, non-quasi kind. So the discovery that using their slightly higgledy-piggledy cousins can not only simplify the problem of finding Hamiltonian cycles, but also massively ramp up the efficiency of the process, is one that is rather exciting, to say the least.

“Our work […] shows quasicrystals may be better than crystals for some adsorption applications,” said Shobhna Singh, a PhD researcher in Physics at Cardiff University and co-author of the new paper. “For example, bendy molecules will find more ways to land on the irregularly arranged atoms of quasicrystals.”

“Quasicrystals are also brittle, meaning they readily break into tiny grains,” Singh added. “This maximizes their surface area for adsorption.”

The paper is published in the journal Physical Review X.

Source Link: Ultra-Complex Fractal Mazes May Hold Key To Future Carbon Capture