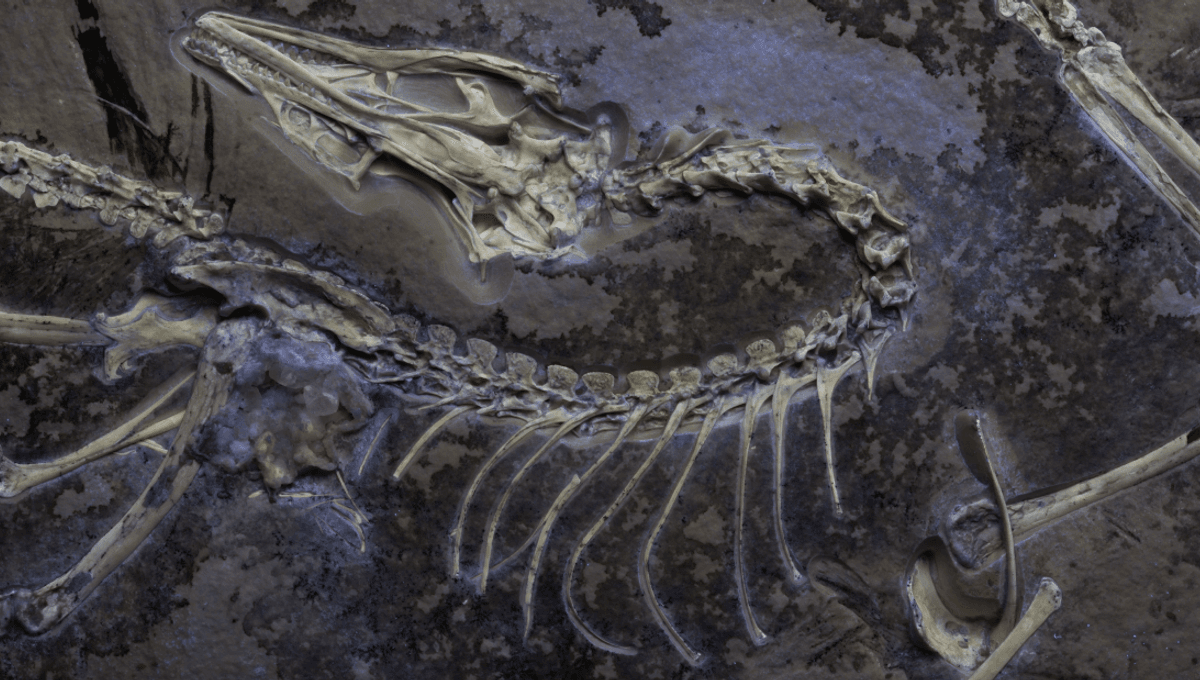

The Chicago Archaeopteryx is a remarkable fossil, the “best preserved” of its kind, in fact. That’s according to palaeontologist Prof Jingmai O’Connor, who’s something of an expert in the transition that saw theropods morph into birds, and here Archaeopteryx is key.

The oldest known fossil bird, it lived during the Late Jurassic 150 million years ago and marked a key piece in the puzzle towards recognizing that all birds are dinosaurs (so yes, that means we are living in an age of dinosaurs). Still, it remains a fossil so there’s been a lot of missing detail in the 13 specimens that have been retrieved in the 160 years since it was first described.

Now, however, the Chicago Archaeopteryx is giving us a major leg up. You see, lucky number 14 comes to us nearly complete and uncrushed, and better yet? It’s fluorescent.

“Soft tissues in most Solnhofen fossils are not visible to the naked eye, but they fluoresce under UV light,” O’Connor, Field Museum associate curator of fossil reptiles and lead author of the paper, told IFLScience. “The fossil bone is also close in color to the rock, but under UV light, the bone glows brightly.”

The Chicago Archaeopteryx is the best preserved, including soft tissues never recovered in a specimen of this iconic fossil.

Prof Jingmai O’Connor

“Using UV light makes it easier for preparators to do their work and to identify soft tissues so that they aren’t accidentally removed. Thanks to the meticulous work of Connie [van Beek] and Akiko [Shinya], the Chicago Archaeopteryx is the best preserved, including soft tissues never recovered in a specimen of this iconic fossil.”

Those never-before-seen tissues included a pivotal set of feathers on its long upper arms known as tertials, which essentially fill in the gap between the body and the arm feathers. It’s a crucial ingredient for flight because it means you don’t lose lift through that gap. It’s likely some of the other 13 specimens also had these feathers, but without the advanced techniques we have today for getting delicate fossils out of rock, they were destroyed.

These feathers are pivotal because, while Archaeopteryx wasn’t the first dinosaur to have feathers or the first to have wings, they indicate it was the first dinosaur that used its feathered wings to fly.

“Birds with long humeri, like pelicans, require a large number of tertials to fill the gap between the primaries and secondaries and the body,” said O’Connor. “It was hypothesized in the ’80s that Archaeopteryx would also need tertials (because of its long humeri), so it’s not a surprise to find them and pretty cool to see that hypothesis validated.”

The absence of tertials also indicates they did not evolve from an ancestrally flying dinosaur and thus supports the hypothesis that flight evolved in dinosaurs multiple times, independently.

Prof Jingmai O’Connor

“Since then, scientists have not really thought much about tertials, not in living birds or in Mesozoic feathered dinosaurs. We found that in non-avian dinosaurs with wing-like arrangements of feathers, the pennaceous feathers have a hard stop at the elbow, indicating a large gap between the feathers and the body. This is further evidence these dinosaurs, like Anchiornis and Caudipteryx, were not flying. However, the absence of tertials also indicates they did not evolve from an ancestrally flying dinosaur and thus supports the hypothesis that flight evolved in dinosaurs multiple times, independently.”

This challenges a hypothesis that suggests flight among dinosaurs evolved from a single ancestor that gave rise to all the other flying dinosaurs. A big news day for palaeontology, then, and it’s like the remarkable detail preserved in the Chicago Archaeopteryx will turn up many more discoveries.

Already, the authors have noted features in the roof of the mouth that may have led to the evolution of cranial kinesis, where a bird’s beak moves independently of its brain case. They also spotted details about their feet that indicate Archaeopteryx spent a lot of time on the ground and may also have been able to climb trees.

Not bad from a fossil about the size of a pigeon, eh?

The study is published in the journal Nature.

Source Link: “Under UV Light, The Bone Glows Brightly”: A Fluorescent Archaeopteryx Just Changed Our Understanding Of The Evolution Of Flight