Tattoos found on the face and arm of an ancient South American mummy are completely unlike any other known examples of ancient body art. Describing the tatts in a new study, researchers say the designs are unique not only in their composition, but also in the type of ink that was used to create them.

Currently housed at the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography of the University of Turin, Italy, the female mummy is believed to have lived in the Andes around eight centuries ago, although exactly when, where and in which cultural group she resided is unknown. Given the flexed position of the body and the presence of textile fragments stuck to the skin, the study authors believe the woman was buried in a “typical Andean mummy bundle” known as a fardo.

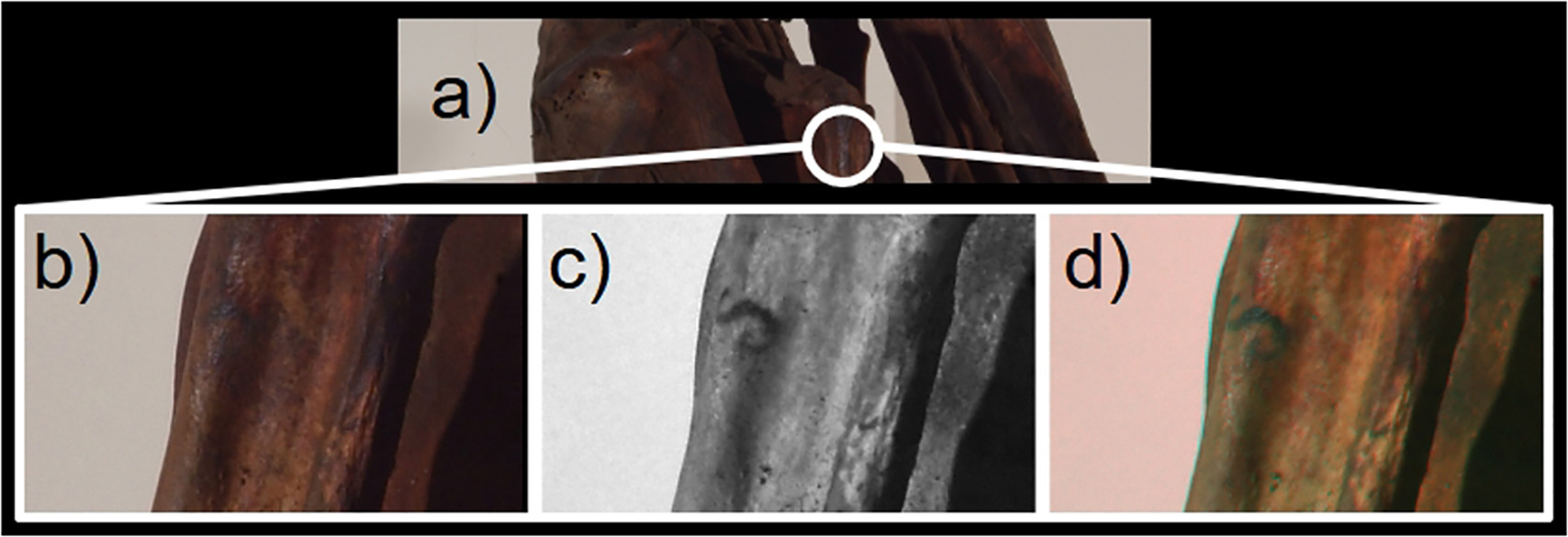

Radiocarbon dating of these textiles has indicated that the mummy died some time between 1215 and 1382 CE, and while some of her tattoos were visible to the naked eye, others had to be revealed using high-tech imaging methods. Unexpectedly, the pre-Hispanic woman turned out to have tattoos on her right cheek, in the form of three widely spaced straight lines running from the mouth to the ear.

“In general, skin marks on the face are rare among the groups of the ancient Andean region and even rarer on the cheeks,” write the study authors. A simple S-shaped design on the mummy’s right wrist, meanwhile, is described as “unique for the Andean region as a tattoo,” with the researchers explaining that “no parallels are known” on other mummified individuals.

The unique S-shaped tattoo on the mummy’s wrist.

Image credit: Mangiapane et al. Journal of Cultural Heritage (2025)

“As far as cultural classification on the basis of skin markings is concerned, the findings from the Turin mummy are unique,” add the authors. As such, they are unable to offer any conclusions as to the purpose or meaning of the tattoos, although the fact that they are located on highly visible parts of the body may suggest that they had a decorative or communicative function.

Using a series of chemical analysis techniques, the study authors were also able to reveal that the tattoos were created with a pigment made from an iron ore called magnetite as well as silicate minerals called pyroxenes. In contrast, charcoal – which was by far the most common black pigment used in ancient tattoos – was surprisingly absent from the ink.

“As far as the Authors know, the use of a black pigment made from magnetite for tattooing has not yet been reported on South American mummies,” write the researchers, adding that “the identification of pyroxenes as tattoo pigment is even less common.”

The study has been published in the Journal of Cultural Heritage.

Source Link: Unique Facial Tattoos Found On 800-Year-Old Andean Mummy Are Unlike Any Other Known