Over the last few hundred years, the human population of Earth has seen an increase, taking us from an estimated 1 billion in 1804 to 7 billion in 2017. Throughout this time, concerns have been raised that our numbers may outgrow our ability to produce food, leading to widespread famine.

Some – the Malthusians – even took the view that as resources ran out, the population would “control” itself through mass deaths until a sustainable population was reached. As it happens, advances in farming, changes in farming practices, and new farming technology have given us enough food to feed 10 billion people, and it’s how the food is distributed that has caused mass famines and starvation.

As we use our resources and the climate crisis worsens, this could all change – but for now, we have always been able to produce more food than we need, even if we have lacked the will or ability to distribute it to those that need it.

But while everyone was worried about a lack of resources, one behavioral researcher in the 1970s sought to answer a different question: What happens to society if all our appetites are catered for, and all our needs are met? The answer – according to his study – was an awful lot of cannibalism shortly followed by an apocalypse.

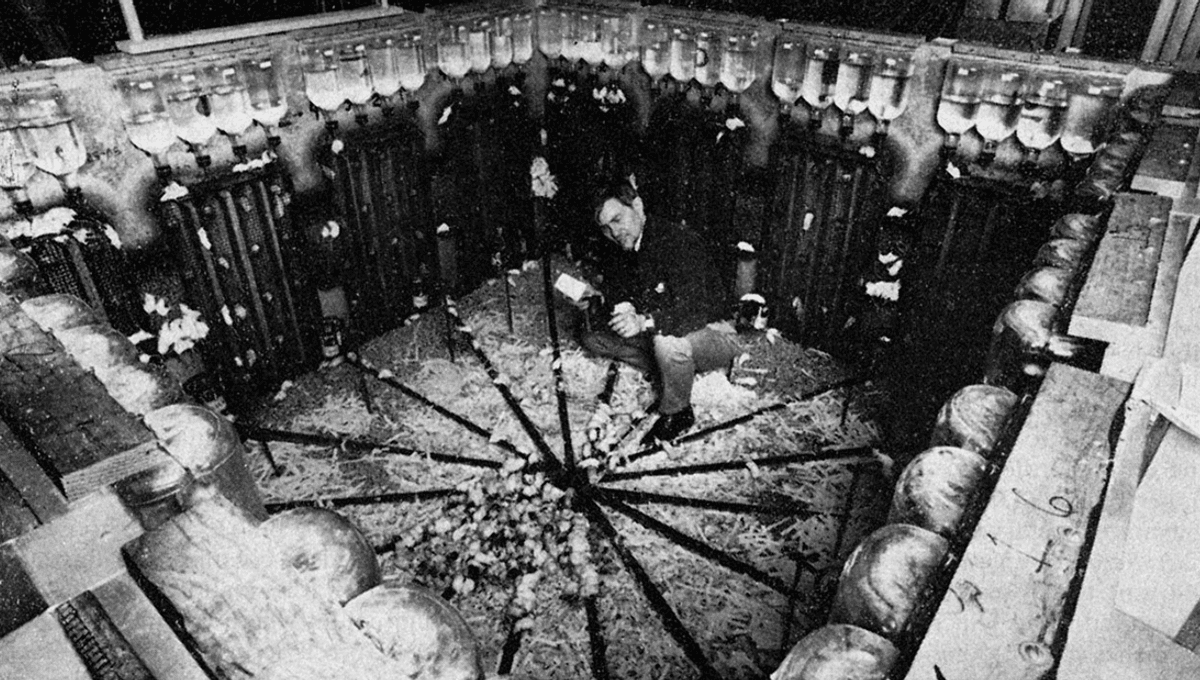

John B Calhoun set about creating a series of experiments that would essentially cater to every need of rodents, and then track the effect on the population over time. The most infamous of the experiments was named, quite dramatically, Universe 25.

In this study, published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, he took four breeding pairs of mice and placed them inside a “utopia”. The environment was designed to eliminate problems that would lead to mortality in the wild.

They could obtain limitless food via 16 food hoppers, accessed via tunnels, which would feed up to 25 mice at a time, as well as water bottles just above. Nesting material was provided. The weather was kept at 20°C (68°F), which for those of you who aren’t mice is the perfect mouse temperature. The mice were chosen for their health, obtained from the National Institutes of Health breeding colony. Extreme precautions were taken to stop any disease from entering the universe.

As well as this, no predators were present in the utopia, which sort of stands to reason. It’s not often something is described as a “utopia, but also there were lions there picking us all off one by one”.

The experiment began, and as you’d expect, the mice used the time that would usually be wasted in foraging for food and shelter for having excessive amounts of sexual intercourse. About every 55 days, the population doubled as the mice filled the most desirable space within the pen, where access to the food tunnels was of ease.

When the population hit 620, that slowed to doubling around every 145 days, as the mouse society began to hit problems. The mice split off into groups, and those that could not find a role in these groups found themselves with nowhere to go.

“In the normal course of events in a natural ecological setting somewhat more young survive to maturity than are necessary to replace their dying or senescent established associates,” Calhoun wrote in the study. “The excess that find no social niches emigrate.”

Here, the “excess” could not emigrate, for there was nowhere else to go. The mice that found themselves with no social role to fill – there are only so many head mouse roles, and the utopia was in no need of a Ratatouille-esque chef – became isolated.

“Males who failed withdrew physically and psychologically; they became very inactive and aggregated in large pools near the centre of the floor of the universe. From this point on they no longer initiated interaction with their established associates, nor did their behavior elicit attack by territorial males,” read the paper. “Even so, they became characterized by many wounds and much scar tissue as a result of attacks by other withdrawn males.”

The withdrawn males would not respond during attacks, lying there immobile. Later on, they would attack others in the same pattern. The female counterparts of these isolated males withdrew as well. Some mice spent their days preening themselves, shunning mating, and never engaging in fighting. Due to this they had excellent fur coats, and were dubbed, somewhat disconcertingly, the “beautiful ones”.

The breakdown of usual mouse behavior wasn’t just limited to the outsiders. The “alpha male” mice became extremely aggressive, attacking others with no motivation or gain for themselves, and regularly raped both males and females. Violent encounters sometimes ended in mouse-on-mouse cannibalism.

Despite – or perhaps because of – the fact their every need was being catered for, mothers would abandon their young or merely just forget about them entirely, leaving them to fend for themselves. The mother mice also became aggressive towards trespassers to their nests, with males that would normally fill this role banished to other parts of the utopia. This aggression spilled over, and the mothers would regularly kill their young. Infant mortality in some territories of the utopia reached 90 percent.

This was all during the first phase of the downfall of the “utopia”. In the phase Calhoun termed the “second death”, whichever young mice survived the attacks from their mothers and others would grow up around these unusual mouse behaviors. As a result, they never learned usual mouse behaviors and many showed little or no interest in mating, preferring to eat and preen themselves, alone.

The population peaked at 2,200 – short of the actual 3,000-mouse capacity of the “universe” – and from there came the decline. Many of the mice weren’t interested in breeding and retired to the upper decks of the enclosure, while the others formed into violent gangs below, which would regularly attack and cannibalize other groups as well as their own. The low birth rate and high infant mortality combined with the violence, and soon the entire colony was extinct. During the mousepocalypse, food remained ample, and their every need completely met.

Calhoun termed what he saw as the cause of the collapse “behavioral sink”.

“For an animal so simple as a mouse, the most complex behaviours involve the interrelated set of courtship, maternal care, territorial defence and hierarchical intragroup and intergroup social organization,” he concluded in his study.

“When behaviours related to these functions fail to mature, there is no development of social organization and no reproduction. As in the case of my study reported above, all members of the population will age and eventually die. The species will die out.”

He believed that the mouse experiment may also apply to humans, and warned of a day when – god forbid – all our needs are met.

“For an animal so complex as man, there is no logical reason why a comparable sequence of events should not also lead to species extinction. If opportunities for role fulfilment fall far short of the demand by those capable of filling roles, and having expectancies to do so, only violence and disruption of social organization can follow.”

At the time, the experiment and conclusion became quite popular, resonating with people’s feelings about overcrowding in urban areas leading to “moral decay” (though of course, this ignores so many factors, such as poverty and prejudice).

However, in recent times, people have questioned whether the experiment could really be applied so simply to humans – and whether it really showed what we believed it did in the first place.

The end of the mouse utopia could have arisen “not from density, but from excessive social interaction,” medical historian Edmund Ramsden told the NIH Record, according to Smithsonian Magazine. “Not all of Calhoun’s rats [which he also experimented on] had gone berserk. Those who managed to control space led relatively normal lives.”

As well as this, the experiment design has been criticized for creating not an overpopulation problem, but rather a scenario where the more aggressive mice were able to control the territory and isolate everyone else. Much like with food production in the real world, it’s possible that the problem wasn’t of adequate resources, but how those resources are controlled.

An earlier version of this article was published in July 2021.

Source Link: Universe 25: How A Mouse "Utopia" Experiment Ended In A Nightmare